The group exhibition Breathing Through Skin has opened on November 7, presenting new and recent works by Mire Lee, Yong Xiang Li, Issy Wood and Pedro Neves Marques. Among them, Mire Lee's newly commissioned piece, Carriers, Horizontal Forms, reflects the artist's philosophical rumination about the concept of Vorarephilia, an internet subculture. With the aid of a pump, two sculptural bodies of different size and volume are connected through an internal circulatory system. When the power is on, the two bodies then become amphibians immersed in a slimy substance, tangled in an interdependent and symbiotic relation.

The article below was written by Alvin Li—curator of Breathing Through Skin—in fall 2019, originally published in Mousse Magazine #79. On this occasion, it is translated ad reprinted here with permission from Mousse editors.

Commissioned work by SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2016.

Presented as a part of the installation 'the way things fall apart-in my wildest dreams'

Often employing minimal, kinetic technologies such as motors and pumps, Lee’s ghostly apparatuses simulate the raw, unruly affects and drives that make or break a subject’s body and psyche. The video footage in Lee’s aforementioned presentation was a compilation of nonsexual sequences that she extracted from Japanese porn—moments of naïveté before the female protagonists are “molested.” A different edit of the compilation first appeared in Lee’s 2016 mixed-media installation Andrea, in my mildest dream. There, four plaster sculptures, one bearing a screen playing the footage, stand in a pool of silicone liquid. Once turned on, the liquid is pumped upward into a Plexiglas box, only to fall again, dripping through holes in the box like an uncanny, cathartic rain.

The installation triggers an eclectic range of affects, from the orgasmic to the sentimental. What sort of bodily fluids is the gooey, milky rain meant to imitate? In conversation, Lee compares her obsession—and identification—with those female porn actors (“Andrea,” as she would call them) to an inexplicable fixation on nightmares and catastrophes. Her response calls to mind that dialectic between sentimentality and its darker undercurrent—a fascination with monstrosity and cruelty—as played out in sentimental literature since the eighteenth century. And while many would claim sentimentality a tool for empowerment, Lee constructs something more ambiguous, even absurd: a scene in which erotics and ethics perpetually feed and undo each other.

Steel, silicone, pvc hoses, grease and other mixed media, kinetic sculpture.

Pavilion Project of the 12th edition of Gwangju Biennale, commissioned by HIAP

Since she relocated to Amsterdam, Lee’s work has taken on more biomorphic forms, while the ambiguity of submission and dominance, victimhood and sabotage, has persisted, further fine-tuned into an exceptional duet—between soft and hard, in material terms. every joint every spine every end (2018) is composed of PVC hoses and steel hooked to a motor and swirling slowly in grease, like pulsating umbilical cords severed from the fetus and yet attached to the mother, or some malfunctioning wetware. In Ophelia when you died (2018) we witness what seems like a mutant abortion as the “organs” (hoses and pipes) violently tear themselves into miserable scraps after running out of lubrication. From these frequent invocations of womb, guts, and mortality one catches a glimpse of an exceptionally original, and provocative, aspect of Lee’s endeavor: the apotheosis of vore1 from its paraphilic origin into a creative attitude and an ontological metaphor. In the erotic desire for the total obliteration of self, just as in an all-engulfing practice, one yearns for that threshold state in which all identity, distance, and meaning collapse. A relationality founded on a state of loss; the abjection of self par excellence.

With the support of Arts Council Korea / Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten

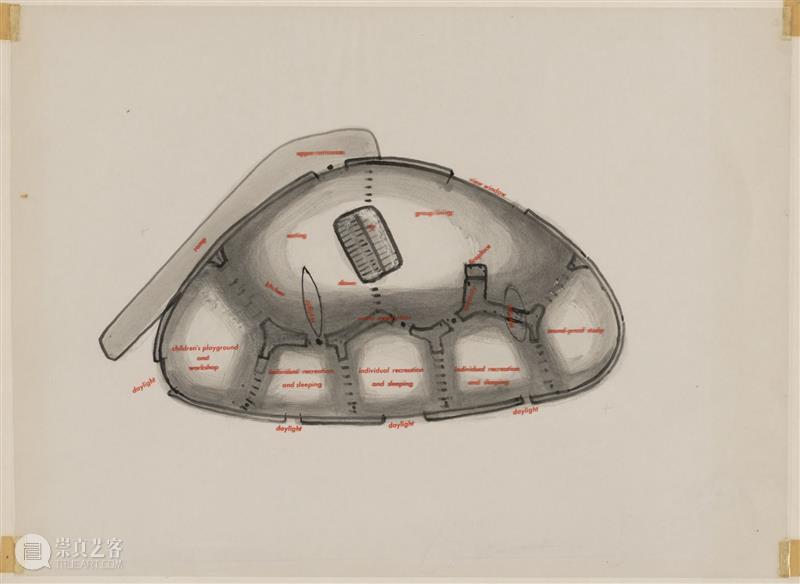

Back to our first encounter: what was missing from the documentation was, as already hinted in its title, a reference to Frederick Kiesler’s Endless House (1947-1960). Kiesler famously conceived of his house as a living organism where all ends meet to perform a sort of self-sufficient cyclicality. I read Lee’s appropriation as a gesture toward something much more somber, a metaphor for cruel entrapment. On a symbolic level, Lee’s abject sculptures—breathless, suffering, doomed to slow death as though by lethal infection—are inmates of our environment. With a ghostly glimmer, they mirror the lived experience of many—certainly, some groups more than others—in this era of universal suffocation. In time, the initial revulsion of their presence slowly dissipates into a sense of “asthmatic solidarity.”2 Like haunting, elegiac poems that chill the spine and curdle the blood, they take our breath away, then let it return with a vital vigilance, to endure.

[1] “Vorarephilia (vore) is an infrequently presenting paraphilia, characterized by the erotic desire to consume or be consumed by another person or creature… Because this sexual interest cannot be enacted in real life due to physical and/or legal restraints, vorarephilic fantasies are often composed in text or illustrations and shared with other members of this subculture via the Internet.” Separating vore from sexual cannibalism is the absence of chewing: “In vore, the victim is swallowed whole, while still alive.” Amy D. Lykins and James M. Cantor, “Vorarephilia: A Case Study in Masochism and Erotic Consumption,” Arch Sex Behav 43 (2014): 181–86.

[2] Borrowing from Franco “Bifo” Berardi’s description of watching the video of Eric Garner’s assassination, in Breathing: Chaos and Poetry (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2018), 15.

Current Exhibition

Mire Lee

Alvin Li

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享