吃苦:三位中国艺术家作品中的哀悼、记忆与母性

Eating Bitterness: Mourning, Memory, Motherhood in the work of three Chinese Artists

1. 哀悼 Mourning

突然,我仿佛被放逐,

这种孤独吞噬着我

广阔而无边……

—赖内·马利亚·里尔克,《Girl’s Lament》

Suddenly I’m as if cast out,

and this solitude surrounds me

as something vast and unbounded…

—Rainer Maria Rilke in Girl’s Lament

2020年初以来,我一直做着奇怪的梦,这些梦是如此真实。在梦中,有时候,我是一个四处寻找母亲的孩子;有时候,我的女儿们又变成小时候的模样,我们正从可怕的危险中逃离。除了全球新冠疫情这个小问题,我会做这些令人心神不宁的梦其实并不意外——我的母亲于二月份去世了,几个星期后,全世界(译者注:因为疫情)都停摆了。在那之前的十年,她生活在一个可怕的老年痴呆世界中,有时问我:“你是谁?你是我妈妈吗?我妈妈在哪里?”

I have been having strange and vivid dreams since early 2020. Sometimes I am a child looking formy mother. Or my daughters are tiny children once again, and we are fleeing some terrible danger. Apart from the small matter of a global pandemic, my disturbed dream life is no mystery—my mother died in February, just a few weeks before the whole world shut down. For ten years before that, living in a fearful world of dementia, she sometimes asked me: “Who are you? Are you my mother? Where is my mother?”

当整个世界似乎都陷入悲伤和恐惧时,我在想我该如何去哀悼,于是我想到了母亲和女儿的主题,我的脑海全部被这个话题所充斥。很久以前,在中国湖南偏僻的农村,不识字的农村女性发明了一种歪歪扭扭的音节文字来记录她们的失落和痛苦。“女书”——一种汉语方言音节表音文字,而非一种语言,也不是什么秘密,尽管围绕着它发展出了很多浪漫的传说——述说着性别差异带来的困难,若是没有女书,这些境遇将无从记载,并被遗忘。婚礼中的哀伤成为了一个女性哀伤的标准化样板,这种哀伤也被称为“哭歌”(哭泣着唱诵),成了婚礼中一道悲伤的程式化表演,因为女孩们准备永远离开她的原生家庭。

As

I work out how to mourn while the entire world seems consumed by grief

and fear, the subject of mothers and daughters occupies my mind. Long

ago, in rural China, illiteratevillage women in Hunan Province invented a

slanted script to write their stories of loss and bitterness. Nüshu—a

syllabary, not a language, and no secret despite the romantic myths that

have grown up around it—was a vehicle to communicate gendered hardships

that would otherwise be unrecorded and unremembered. Bridal laments—or

kuge (crying songs), stylised performances of grief sung at weddings as

girls prepared to leave their natal families forever—became a female

canon of lamentation.

我发现我很希望举办这样一个悲伤的仪式。但充满慰藉的哀悼仪式因为Covid-19新冠疫情而无法实现,我感到茫然。最后只有一场我自己和我的女儿参加的葬礼,(我所期待的)一场纪念她生命并挥洒她的骨灰的大型聚会被无限延期,这让我不知所措。过去的几个月,我都沉浸在悲伤中,试图振作并调动起写作的意愿,我想到了之前与不同的女性进行过的关于女儿、母亲和祖母的各种对话。

I

find myself wishing for such a convention of sorrow. Denied consolatory

rituals of mourning by Covid-19, I am at a loss. A funeral with only

myself and my daughters in attendance, a larger gathering to celebrate

her life and scatter her ashes indefinitely postponed, has left me in a

kind of limbo. Drifting through months of sadness, trying to summon up

the will to write, I turned to my various conversations with other women

on the subject of daughters, mothers and grandmothers.

2. 记忆 Memory

在这段封闭和停摆的日子里,我重新审视了过去十年来我和一些中国女性艺术家的采访。由于无法返回中国,我和她们又进行了一些无法面对面的采访。我也在反复阅读以前的采访文字,重听双语的采访录音,这些声音不时地被倒茶声、电话声以及无处不在的犬吠声所打断,她们都生活在北京郊区的艺术家村里。我非常震惊,这些对话竟然成了关于最原初亲子关系的痛苦回忆。

Through

this time of closed borders and lockdowns, I revisit my interviews with

women artists in China over the last decade. Since I cannot return to

China, I have conducted new interviews in the virtual realm. I’ve also

been reading old transcripts and listening to conversations recorded in

two languages, always punctuated by the sound of pouring tea, ringing

phones, and the ubiquitous barking dogs that wander around the artists’

villages in Beijing. I am struck by how often these conversations turn

to difficult memories of primal maternal relationships.

我曾与很多女性交谈,有的女性的父母对她们不是男孩深深失望;有的女性的母亲因为“打倒右派”而被监禁或流放,母女分离;有的女性特别渴望能多生一个孩子(当时中国还是独生子女时代);有的年轻女性,她们的母亲在特殊时期被剥夺了受教育权,这些母亲也让孩子承受了很大压力。这些都是复杂的母系联系,受到政治历史、社会变革以及父权制的权力和赞助体系的干扰。在文革初期出生的女性经历了自己的母亲与儒家思想所要求的“好母亲”形象的脱节。而如今,“一孩政策”的产物——年轻一代女性则承受着养育两个孩子的压力:妇女的生育权仍然受父权制国家所控制,而且似乎仍然需要继续“受苦”。

I

have talked with daughters whose parents were bitterly disappointed

they were not sons; with daughters separated from mothers imprisoned or

exiled during the anti-rightist campaigns; with mothers who desperately

wanted more than the one permitted child, and with younger women

pressured by mothers who were denied their own education during the

Cultural Revolution. These are complicated matrilineal connections,

ruptured by political history, social change and patriarchal systems of

power and patronage. Women born at the start of the Cultural Revolution

experienced the untethering of their own mothers from

Confucian-inflected ideals of ‘the good mother’. A generation of younger

women, products of the One Child Policy, are now being pressured to

have two children: women’s fertility is still controlled by the

patriarchal state, and it seems they are still required to ‘eat

bitterness’.

作为一名母亲,或者女儿,究竟意味着什么,关于这个话题的讨论从未停止。我最近与三位艺术家的对话呈现了她们是如何驾驭情感的余波,以及她们的作品是如何审视性别观念的。

What

it means to be amother, or to be a daughter, is continually reinvented.

My recent conversations with three artists reveal how they navigate the

emotional fallout, and how their work interrogates notions of gender.

3. 母性:吃苦 Motherhood: Eating Bitterness

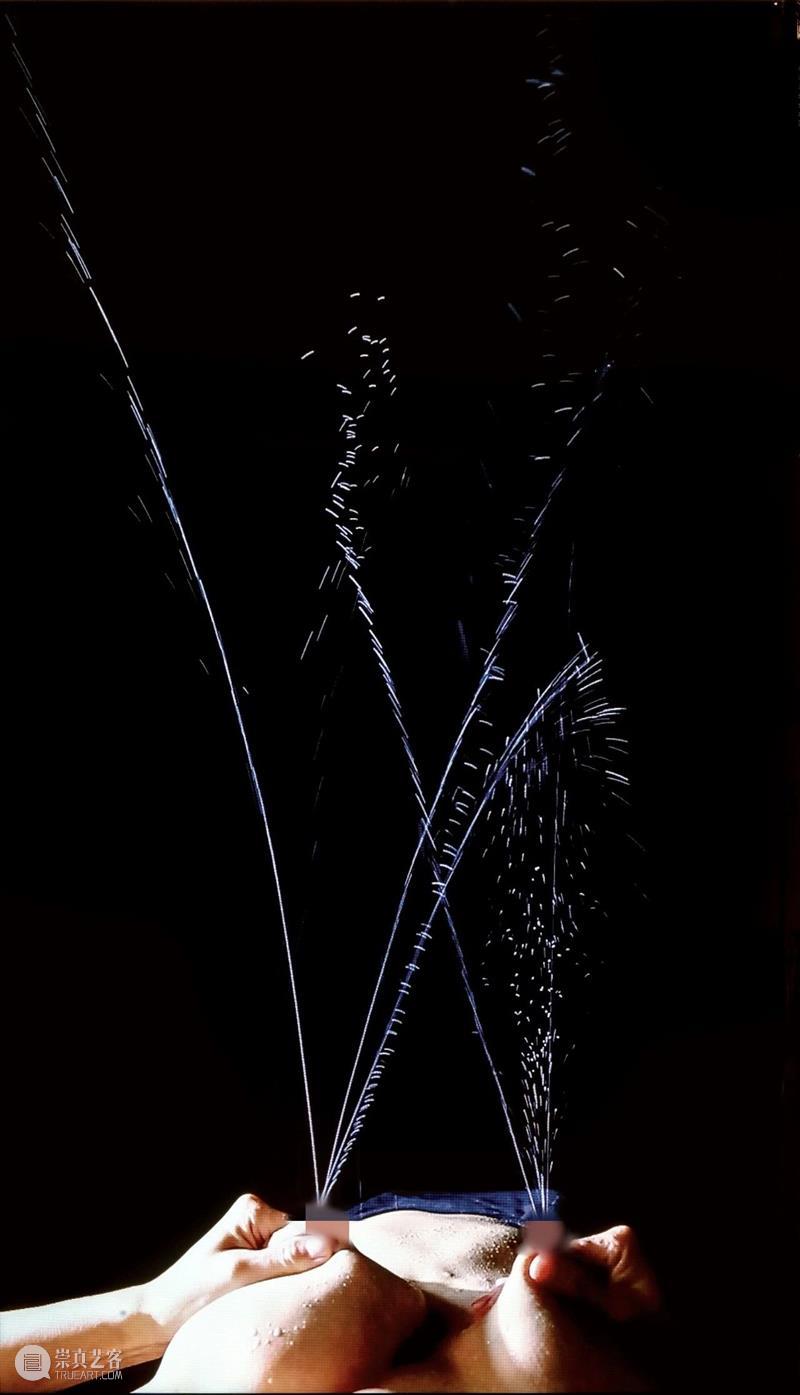

我与曹雨通过微信和邮件进行了多次对话,谈到了使她在北京一度声名狼藉并同时名声大噪的影像作品《泉》(2015)。这部作品首次展出于中央美术学院的研究生毕业展上。她平躺在床上,摄像机镜头从她头顶后方的平行视角进行拍摄,她哺乳期的身体正对着天花板。她在作品中运用了戏剧性的明暗对比,竖立的录像屏幕底部中呈现出艺术家的双手正有节奏地捏挤着她的一对乳房,明亮而洁白的乳汁突然向上空猛烈地喷射而出。多么唯美、本能、真实、有趣——并且如此颠覆!她的作品名称暗指杜尚破败的现成品(仰面向上放置的陶瓷小便池)和布鲁斯·瑙曼(1966-7)的作品(展示了这位美国概念艺术家从嘴里吐出的弧形水柱),曹雨的《泉》消除了这两件“开创性”作品中具有的阴茎潜台词,并打破了男性凝视。

In

my conversation with Cao Yu via WeChat and email, we spoke about the

video work that made her notorious in Beijing. Shown at her Central

Academy of Fine Arts graduation exhibition, Cao’s video Fountain (2015) is shot from her ownpoint of view as she looks down at her lactating body.

At the bottom of a vertical video screen, in dramatic chiaroscuro, jets

of milk spurt into the air as the artist’s hands

rhythmically squeeze her breasts. It’s aesthetically beautiful,

visceral, funny—and very subversive. With its title alluding to Marcel

Duchamp’s iconoclastic readymade (a porcelain urinal turned on its side)

and to a 1966-7 work by Bruce Nauman (showing the American conceptual

artist spitting out an arc of water), Cao’s Fountain deflates the phallic conceits of the two ‘seminal’ works and disrupts the male gaze.

曹雨,《泉》,2015年,单频道高清数码录像(彩色,无声),11'10",10版 + 2AP,图片提供:艺术家及麦勒画廊

Cao Yu, Fountain, 2015, single channel HD video (colour, silence), 11’10’’, edition of 10 + 2 AP; image courtesy the artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne

通过这件作品,曹雨让我们看到了新的母性光辉,一种精疲力竭与令人振奋的奇怪组合。当时,曹雨患上了频繁发作的乳腺炎,并因此高烧,承受着难以忍受之痛。这也是为什么乳汁对于她而言是既爱又恨,令其备受折磨又强烈解脱的婴儿营养和生命能量。但是曹雨也因此突然意识到女性身体内部所蕴藏着的无限力量。她说,她的两个乳房就像一座活火山:“我敏感的意识到自己此刻的身体正充满着无穷无尽的生命能量与爆发力,我第一次感受到作为女性,我的身体甚至可以拥有比男性更加猛烈的喷射力和释放张力,而我的身体正逐渐化为一座具有雄性色彩的喷泉纪念碑。”

Through

this work, Cao makes us see new motherhood as a strange combination

ofexhaustion and exhilaration. At the time, the artist was suffering

from mastitis, which causes high fevers and unbearable pain, so to

express her milk was both excruciating and an exquisite relief. But Cao

was also newly aware of the power of the female body; her breasts, she

says, were like active volcanoes: “I felt for the first time as a woman

that my body could have aneven more violent power to release tension

than a man’s.”

Cao Yu, Everything is Left Behind, 2019, canvas, fallen long hair (the artist’s), h.135cm, w.90 cm; courtesy artist and Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne

Cao Yu, Everything is Left Behind, 2019

Cao Yu, Everything is Left Behind, 2019, detail

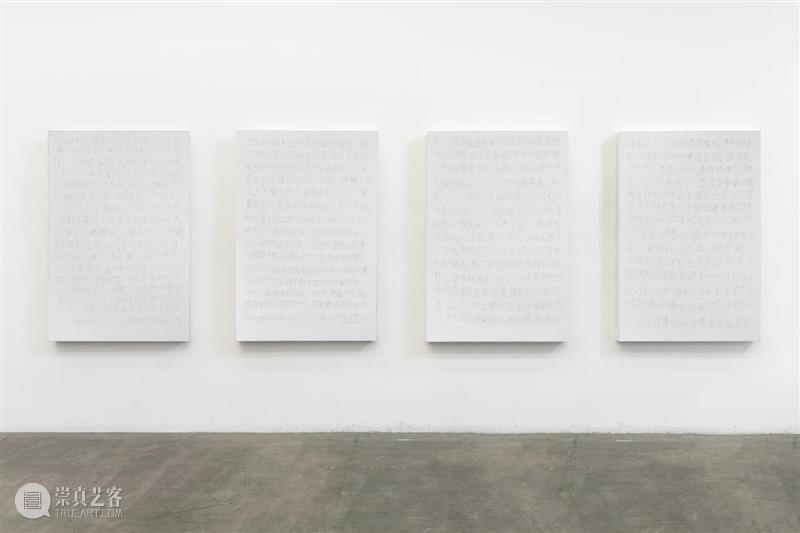

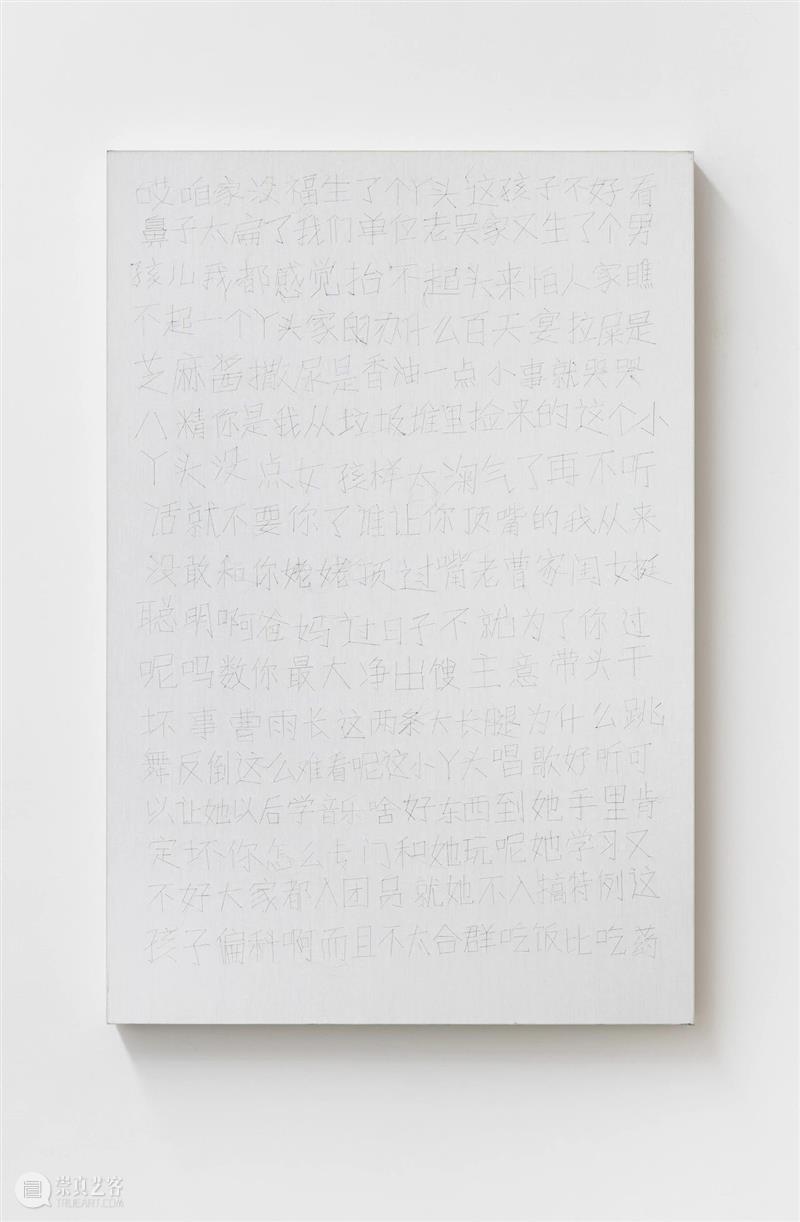

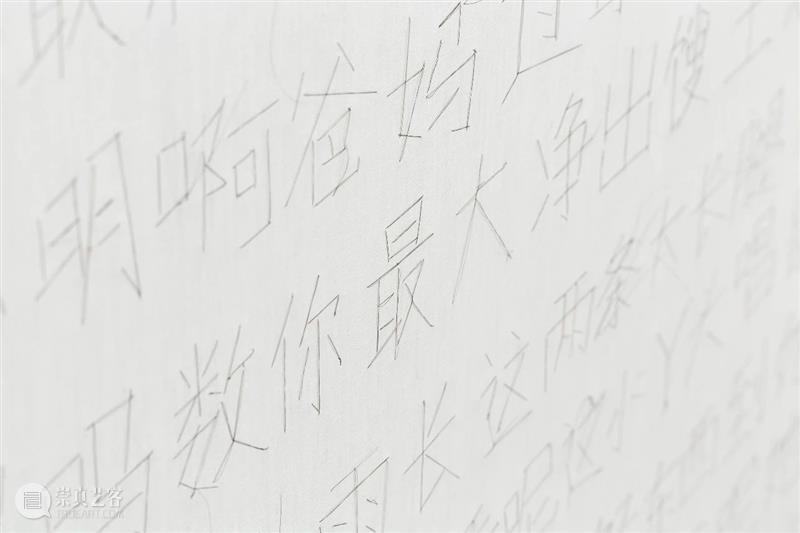

而在她的作品《一切皆被抛向脑后》(2019)中削弱了女性的力量感,从而明确地展现了大众价值观如何定义女孩和女性。白色画布上缝着很多话语,这些语句揭示社会对于女性根深蒂固的文化信仰,而缝字的线不是别的,正是曹雨本人长长的黑发。第一个画面以1988年艺术家的父亲在其出生时所说的一句话作为开篇:“哎, 咱家没福,生了个丫头......”比如另一个画面中写道:“这个丫头没点女孩样太淘气了,再不听话就不要你了......”该系列后来的一些画面上强调了曹雨周边的人在学业及保持美丽上给予的压力:“你看你现在都胖成什么样了,吃啥啥没够,一个姑娘家这样还不让人家笑话......”从这些作品的表面——用头发缝着的每一个笨拙的汉字——愤怒和悲伤的混合体是显而易见的。

Everything is Left Behind

(2019) undercuts that sense of female power with explicit references to

how girls and women are valued. White canvases are embroidered with

sayings that reveal deep-seated cultural beliefs about women; the thread

is Cao’s own long black hair. The first panel begins with a quote from

the artist’s father at her birth in 1988: “Alas, we are so unlucky, we

gave birth to a baby girl’. Another reads: ‘If you’re not a good girl, I

will abandon you.” Later works in the series emphasise parental

pressure to succeed academically and also to be beautiful: “Look how fat

you are, there’s never enough food for you.” In the physicality of

these works—their awkward Chinese characters sutured with hair—a

simmering mixture of anger and sorrow is palpable.

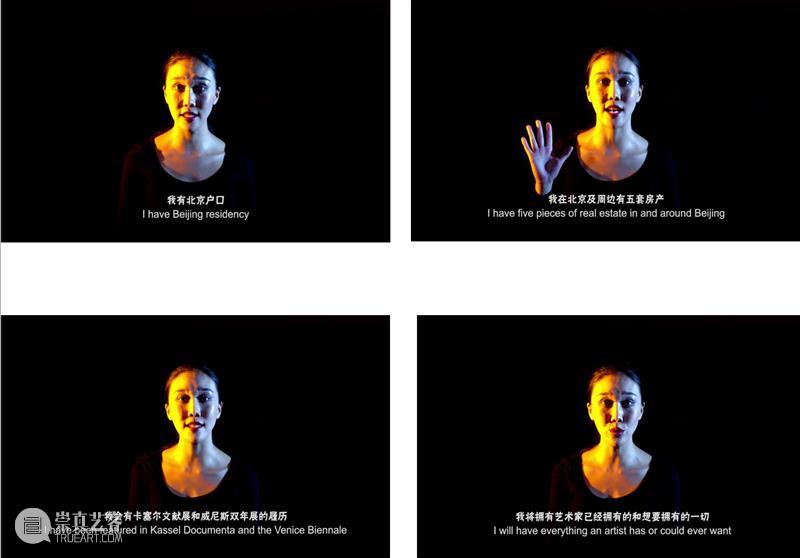

在其作品《我有》(2017)中,则更尖锐地审视了性别压力。直面镜头,曹雨正不断地炫耀着。她从女性外表开始(“我有令人羡慕的曼妙身材……我有水蛇腰……”),然后是她的婚姻(“……我有一个爱我,把我宠上天的老公……”)并补充道:“还有一个堪比神童的儿子。”曹雨讽刺了现今时代下社会中人们追求成功的野心、物质积累、消费主义欲望等价值观:“我将拥有艺术家已经拥有和想要拥有的一切……”但要真正取得成功,似乎女人应该生出一个聪明的男孩。曹雨公然挑战了人们对于女性应该谦逊和优雅的既定性别预期。她说:“这让我意识到生活中很多情况下存在的真实与虚假,它们的边界竟是如此模糊。人们被迷惑其中而无法辨别真假,并喜欢自我安慰式的希望看到听到的都是弱者,以维护那颗脆弱的玻璃心。”

I Have

(2017) examines gendered pressures more pointedly. Speaking to the

camera, Cao proceeds to boast. She begins with her appearance (“I have

an envy-inducing figure… I have an hourglass waist…”), her marriage (“… I

have a husband who dotes on me…”) and adds: “I have a child prodigy for

a son.” Cao satirises the ambition, material accumulation, consumerist

desire and success of the Chinese zeitgeist: “I will have everything an

artist has or could ever want…”yet to be truly successful, it seems, a

woman should produce a “child prodigy for a son”. Cao also defies the

expected gender performance of modesty and humility. She says, “People

are unable to distinguish between genuine and fake, and what they really

like to hear and see is weakness in a self-comforting way, to protect

their fragile glass hearts.”

Text by Luise Guest

英文文章节选自Luise Guest受邀为澳大利亚4A当代亚洲艺术中心撰写的评论文章,文章发布于4A当代亚洲艺术中心官方网站,请点击“阅读原文”了解更多信息。

English text excerpted from the text by Luise Guest. The text was originally commissioned for 4A Papers in 2020 by 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Australia. Please click "read more" to get more info.

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享