Edouard Malingue Gallery is pleased to share the fifth edition of our online journal 《 》featuring Yu Ji (b. 1985, Shanghai, China).

The journal was created with the idea to provide another space to understand our artists’ practice, through casual conversations about their closest surroundings. There is no clear meaning to the journal hence the title,《 》. Included in the journal is a conversation between Lai Fei and Yu Ji.

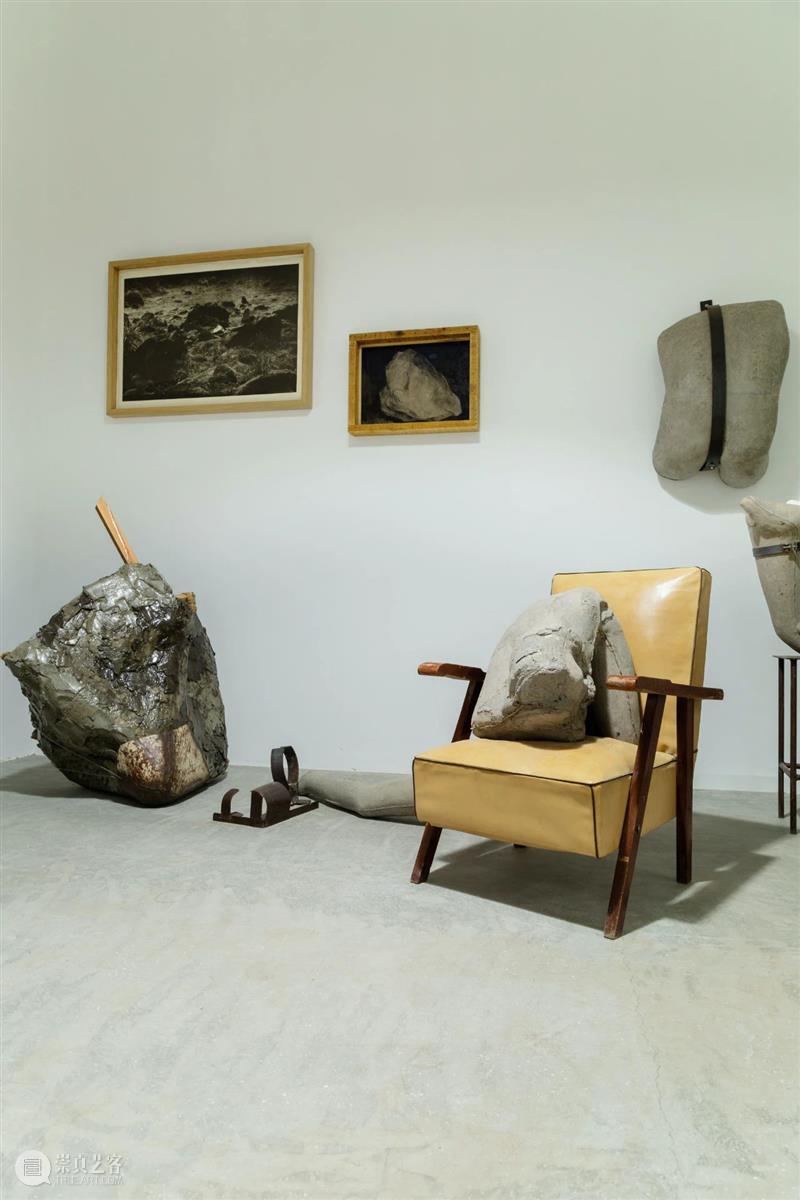

A revisitation of sculpture, an extension of its three dimensionality and attunement to body, context and narrative, is at the heart of Yu Ji’s practice. Her work, that spans installation, video and performance, exists as a series of interventions, both into space and creating it, taking medium and materiality as a starting point. Creating her own language, Yu Ji enlivens her visual sentences with a rich vocabulary rooted in form, objects, humanity and the everyday. Yu Ji obtained her MA from the Department of Sculpture, College of Art of Shanghai University, in 2011. In 2008, she co-founded AM Art Space – an artist-led space in Shanghai, promoting experimentation and exchanges between artists, curators and the public. Yu Ji has exhibited globally, including Chisenhale Gallery, London (current, 2021), Centre Pompidou x West Bund Museum Project, Shanghai (current, 2021), BASEMENT ROMA, Rome, Italy (2021), HOW Art Museum, Shanghai (2020), the 58th Venice Biennale (2019), Tensta Konsthall, Sweden (2018), Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai (2017), 11th Shanghai Biennale (2016), Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2014), amongst others. In 2017 Yu Ji was nominated the Hugo Boss Asia Art Award. The artist lives and works between Shanghai and Vienna.

Editor's Note

For many who work in the art field, it is seemingly a tacit consensus that there is no explicit boundary between life and work. That work, or the act of creating, can fit seamlessly into everyday life sounds like an emancipation and resonates with the Marxist vision of the ideal all-around development of people. However, life often transmogrifies itself into a beast, to invade all destructible frames, to smother all breathers and beautification. Perhaps 2020 is a year that confronts many of us with that experience. People don’t often talk about the delicate plight of female artists who work from home under such circumstance. Time becomes fragmentary, and childrearing and working rotate in a fast alternation or even take place simultaneously—that is my observation when visiting Yu Ji’s new studio and residence in suburban Fengxian. The year before last, Yu Ji’s life was joined by a new family member; in the beginning of this year, she moved her studio and her residence once located in different districts of Shanghai to the multi-storey house by the sea, allowing a new way of life to unfold on the city’s outskirts. The worldwide outbreak of COVID-19 has forced Yu Ji’s schedule of overseas shows and travels into either cancellation or postponement. Such situation has also magnified the act of “living” itself in the isolated suburbs. In the fragmented time between dealing with “life” issues, I got a chance to chat with Yu Ji about work, while realising that the two are indivisible after all.

Lai Fei: What have you been up to recently? It’s been a while since last time I saw your works on view in Shanghai, and I’m curious about your new work exhibited in Interrupted Meals at HOW Art Museum.

Yu Ji: I’ve been busy with several domestic group exhibitions later this year, and there are two personal projects of mine that remain pending, both unconfirmed due to the COVID-19 situation, but I’m trying to keep up with the original plan of creating. I will present one new piece in the group exhibition at HOW Art Museum; it continues with my earlier combination of cement body sculpture and urban ruins, and it comes much larger in size than before.

Lai Fei: Does your new piece that Interrupted Meals features employ your wonted method and leave a part of creation to be conducted on the site?

Yu Ji: Actually, most of my works that consist of onsite creation are projects that I’m commissioned to carry out, so I have more flexibility in the time for preparation and in the space for displaying. The work in Interrupted Meals is not an utter onsite creation, though it brings along such vibes. I used a great deal of second-hand rebars, and I wanted to present a sculpture endued with mobility in an unfinished and ongoing form. One day on a demolition site, I saw giant cranes tearing down houses and crushing rebars; it was so rousing that I watched for a good while. It could be the tremendous motion or the humanlike destructive power that enthralled me; I can’t tell what it is, but I want to get close to it through artmaking.

Lai Fei: Both your depiction of mobility and the video that documents cranes in operation deliver a kind of lightness—that is actually quite paradoxical. I’ve been to a demolition site with you, and I know the force of a crane hoisting rebars is beyond human power, though it looks as nimble as stir-frying in a pan.

Yu Ji: You’re right. The rebars used in the work shown at HOW Art Museum weigh more than 300 kilograms.

Lai Fei: I watched the video of cranes many times. My captivation may differ from yours, but I can feel something that your works embody too, such as rhythm and physical movement.

Yu Ji: Rebars of varied lengths and widths are tossed around in the giant hands of a crane until they become a big ball, it’s bizarre.

Lai Fei: The perspective of mankind humanises it automatically, so it is somewhat like a claw machine, or resembles a bird nesting, which incorporates an indescribable tenderness.

Yu Ji: Now this 300kg big ball is cast beside where I live, like a hill and impossible to move an inch. I climbed up to mold some cement. The gentle destructive power within is reserved in the video.

Lai Fei: I recently read Tongues of Lykavittos which you published on Heichi magazine. What you wrote reminded me of Nüwa creating humanity, especially in thinking about your more figurative sculptures. You and I have discussed before that traditionally “mountain” is regarded as something masculine. Mountaineering—especially as your Pataauw Stone (2015) executed in Beitou encapsulates—is like some sort of undisguised grapple. “Grapple” may not be the word and it’s probably easier to be likened to how you arrive at a certain limit with the use of your body and energy in that natural setting.

Yu Ji: Yes, that’s visible in the video. To be honest, I felt quite ashamed when I watched the video, for I tried so hard and looked awful, but the work made in Beitou wasn’t envisaged to be like that.

Lai Fei: I happen to think “trying so hard” is indeed the sincerity and charm in many of your works. Perhaps “trying so hard” or “trying to the fullest to live a life” ought not to be an aesthetic or formal pursuit.

Yu Ji: I wanted to look good though, and the outcome isn’t always as good.

Lai Fei: Maybe it turns out to be a different beauty in the end.

Yu Ji: That reminds me of a remark Yan Jun made about me in an article: “she sweats heavily”. I felt embarrassed. Perhaps I just overexert wherever I try.

Lai Fei: In terms of self-consciousness about the body, females may be more prone to inhibition and vulnerability. When making Pataauw Stone, is there any choreographic idea to control your movement?

Yu Ji: No, nothing choreographic at all. The idea of the Beitou project was to carry my stone—something I treat as the most intimate part of my body—to seek unrevealed secret landscapes.

Lai Fei: Is your exhaustion opposed to your expectation?

Yu Ji: Yes, I didn’t expect it to be so exhausting, as if it were killing me and couldn’t be finished. Finally, I made it to the end but earned myself a fever. I did not plan to make it a hard mission based on stamina and willpower. I tend to overexert, or maybe I always make wrong efforts, and such clumsy tendency faintly meddles in my practice. I come to realise that I have naturally become this way. What I did in Beitou is Part I, and I have an idea of Part II, conceived to be carried out in a desert in America.

Lai Fei: But, meanwhile, in many of your works, however tender, organic or light the objects and materials that attract you seem in an abstract sense, as a matter of fact, they need massive physical power and willpower to manage.

Yu Ji: That’s why I can’t prevent sweating, or I would feel unnatural.

Lai Fei: Perhaps perspiration is a signal of how much your body is engaged.

Yu Ji: I’m not sure, but body has always been my most direct instrument; I am a manual worker.

Lai Fei: Your “clumsiness” may be interpreted as not seeking any knack or shortcut to ease yourself.

Yu Ji: And it’s more of an instinct, a physical awareness and mental unawareness. Probably it results from my sculpture training over many years. Sculpture training is a body training.

Lai Fei: Indeed, you are keen on challenging and surpassing the boundary of sculpture within a studio, which positions you in an environment of uncertainty and fluidity.

Yu Ji: Exactly. That’s what attracts me the most. An “uncertain” environment can also be put as an unfamiliar and strange one.

Lai Fei: Such as placing 300kg wasted rebars in front of your door, which is incredible.

Yu Ji: Yes, the residential management was mad, and neighbours too are puzzled but dare not ask me. Earlier when my studio was at that pen factory, they thought I was a scrap collector and root carving crafter.

Lai Fei: In a way this little hill made up of rebars appears more impactive in front of your house than in a museum gallery.

Yu Ji: Absolutely. It was thrilling to transport rebars with a forklift truck.

Lai Fei: It evokes an image of little human beings moving mountains.

Yu Ji: I proposed the idea of using rebars to several museums, but all got declined out of safety concerns. I adapted a little bit this time, and finally it’s materialised.

Lai Fei: I’ve always looked forward to your presentation in Shanghai, as in here there is a stronger connection with this land.

Yu Ji: What I really want to present is a sense of ruins, urban ruins. The existence of body is also a wilderness, contorted and folded like a wasteland. Self-consciousness is already detached from corporeality.

Lai Fei: Listening to your verbal description, I would feel that the scene of ruins is quite gloomy, but the “wilderness” in your depiction is not merely bleak and barren.

Yu Ji: It’s double-sided, I think, and spreading toward two extremities. One’s interpretation of ruins varies from another’s, and to me, ruins are enchanting; the abandoned and deserted is more enchanting than the attended and occupied.

Lai Fei: In other words, places where traces of human presence fade away.

Yu Ji: Places where humans leave behind.

Lai Fei: What touched me greatly about the deserted school you brought me to in Fengxian was the verdure there. After humans left, such places abound with more exuberance instead.

Yu Ji: I love such places too! Freer and unconstrained.

Lai Fei: Since you moved to Fengxian, have you had more room to approach and establish that sense of ruins? We’ve talked before about how the size and location of your studio influence your sculptural creation.

Yu Ji: It’s ok, actually. In downtown there were many demolition sites too, though the atmosphere was somehow different. Speaking of the size of studio, I’ve always been fonder of relatively congested spaces, and my studios have always been modest.

Lai Fei: A major characteristic of deserted old houses in Shanghai is also the size, namely, the density of population who once dwelled there.

Yu Ji: As for the location of studio, I was in residence here and there for the last five years, so studio was mobile to me, and the one in Shanghai was like my heart. Now the change of studio is more out of the change of life.

Lai Fei: This year is very special, as most “mobility” and travels fall through.

Yu Ji: Yes, the beginning of this year was drastically impacted. All was shackled up.

Lai Fei: At the same time, your life and working environment went through changes. The external change, caused by the pandemic, and the change of your life happen to overlap.

Yu Ji: Yes. Having a child and moving to the suburb are two things that made my life and work feel isolated all of a sudden.

Lai Fei: And under such circumstance of isolation, on top of social distancing, life itself, as well as the physical energy it requires, is magnified.

Yu Ji: It challenged me a lot. My adaptability and resilience are pretty bad in this regard, and those are what I was mainly working on in the first half of this year during the outbreak.

Lai Fei: This is consistent with the “clumsiness” in your works that we mentioned just now. In life, you seem not to be a person who seeks knack or shortcut. I think that separating life and work may not apply to you. In your home and studio in Fengxian, your status being a mother and artist is integrated. Like we have said before, the most visible condition is that your studio and living space are conjoined, and I think such spatial awareness is quite feminist. An unmixed and undisturbed period of time in studio, and the distinct separation of working and living spaces, can be interpreted as a masculinist mode of working in contemporary society.

Yu Ji: Exactly. It is over the last two months that I’ve come to realise it.

Lai Fei: Not separating the work-life space and mode can be very consuming. I guess that means you’re up against all needs at all times.

Yu Ji: And I wasn’t mentally prepared for all this, can only grope my way ahead.

Lai Fei: I remember your analogy in Tongues of Lykavittos about creating bodies out of mud—life consumes soil, just like how childrearing consumes female bodies.

Yu Ji: Compared with the scene of ruins in the work we talked about earlier, another kind of vitality may have been nurtured in recent years. There are new things happening in life which require more commitment and stability. Today I just turned the soil for my aloes; their roots have almost surfaced, and one pot has turned into four!

*The interview was taken during June 2020.

Click Read More or scan the QR code below for

online journal 《》, Yu Ji

Image courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery

Photo by Quentin Qiu

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享