Opening

June 5, Saturday

Guid Tour

11: 00-11: 30

14: 30-15: 00

17: 00-17: 30

Opening Time

10.00am - 6.00pm, Tuesday to Sunday

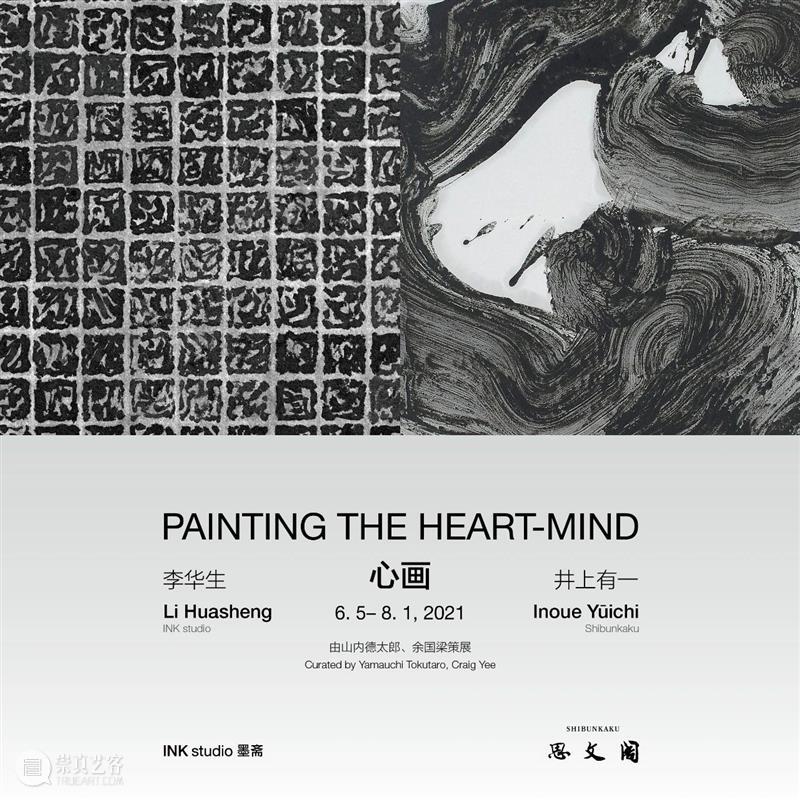

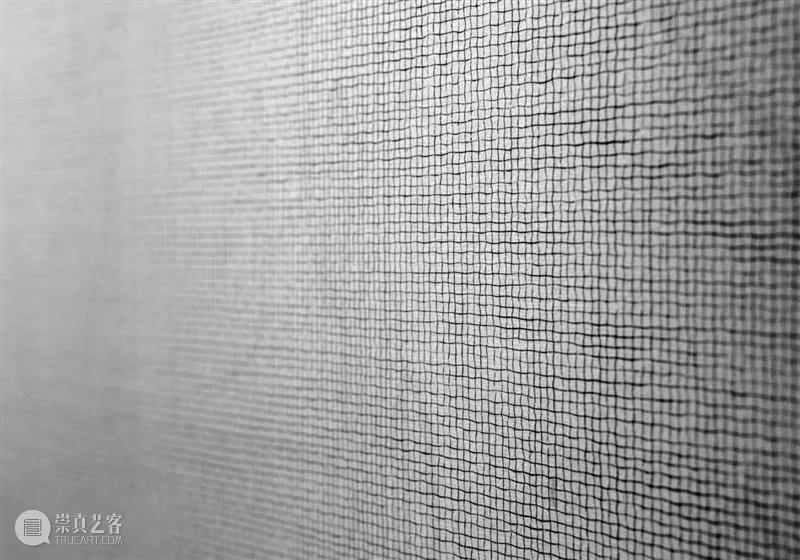

Painting the Heart-Mind: The Art of Inoue Yūichiand Li Huasheng installation view

INKstudio, Beijing, Shibunkaku, Kyoto, and the Li Huasheng Art Foundation are co-organizing a dual artist exhibition of modern calligraphies by post-war, Japanese calligrapher Inoue Yūichi(1916–1985) and abstract paintings by post-Cultural Revolution literati ink painter Li Huasheng(1944–2018). As part of the exhibition, the major single-character works Yama(1966), Hin(1972) and Taru(1973)—last exhibited and published in Inoue’s solo retrospective at the Kanazawa Museum of Contemporary Art in 2016 [1]—will be exhibited in China for the first time accompanied by eight other rarely seen calligraphies that document the breadth of Inoue’s artistic practice. Contemporaneously, a selection of early landscapes, abstract grid paintings and late abstract landscapes by Li Huasheng will be exhibited alongside the eleven works by Inoue. This visual juxtaposition gives viewers an opportunity to rethink debates about tradition and modernity often couched in terms of East and West as, instead, a dialog within East Asian between post-war Japan and post-Cultural Revolution China, between calligraphy and painting, between Buddhism and the arts, and between two socio-cultural icons and iconoclasts.

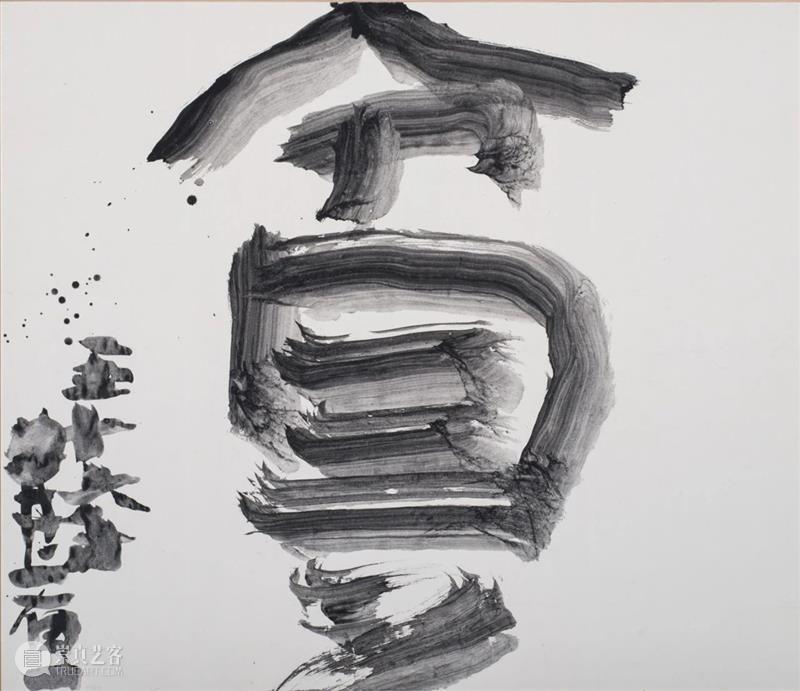

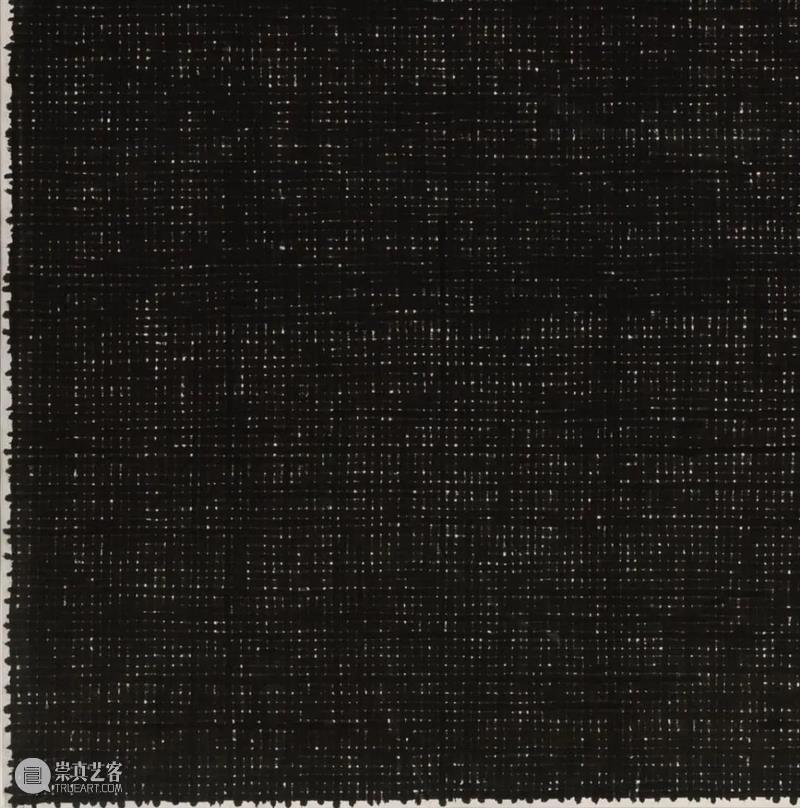

Inoue Yūichi, Hin [Impoverished], 1972, Ink on Japanese paper, 106 x 123 cm

Inoue Yūichi

During the post-war period, a group of avant-garde calligraphers lead by Morita Shiryū and Inoue Yūichi broke away from the calligraphy establishment and formed Bokujinkai as a modern, egalitarian movement in which calligraphers could practice their art with the freedom and autonomy of contemporary artists.[2]

Of the Bokujin calligraphers, Inoue Yūichi’s artistic path was perhaps the most radical. Inoue developed a theory of calligraphy as the quintessential contemporary art form: at its core, calligraphy brings linguistic meaning, sound, symbolic picturing and expressive gesture together into a unified expression; in addition, because everyone in society can write, calligraphy is the art form closest to people’s lives. [1]

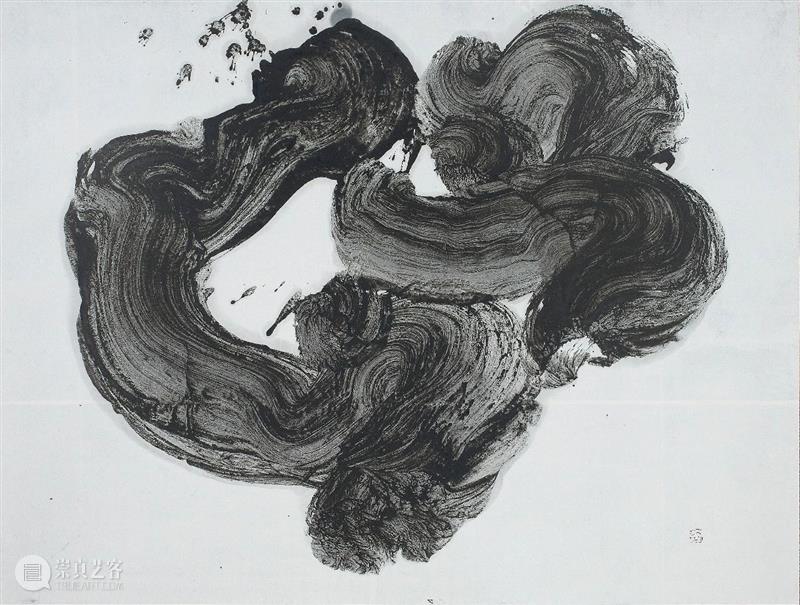

Inoue Yūichi, Yama [Mountain], 1966, Ink on Japanese paper, 146 x 231 cm

Rejecting the tradition of inscribing classic literary, philosophical or religious texts, Inoue developed a practice of rendering single words thereby treating individual characters—selected for meaning, shape and sound—as objects for artistic contemplation and transformation. Inspired by his early experiments in pure abstract calligraphy using black enamel, Inoue also altered the material constituents of his ink to expand its expressive range. [1] As a result, in Inoue’s calligraphy one can follow the movement, path, angle, speed and pressure of his brush—including its tip, body and heel—with almost complete fidelity. In this way, Inoue created a material medium and visual language of tremendous transparency and he used this new language to pursue an art of raw and utter directness.

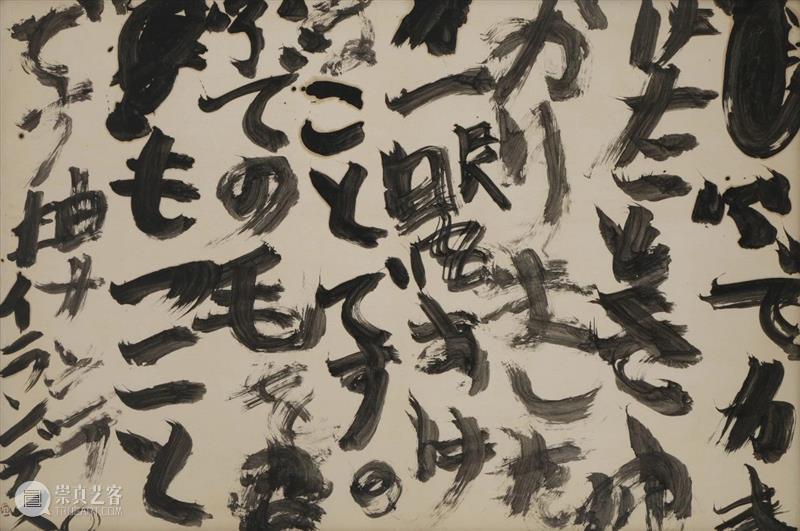

Inoue Yūichi, Fude ga Mogeta Toki (When my brush came apart), 1976, Ink on paper, 80.5 x 119.5 cm

Li Huasheng

In the early half of his career, Li Huasheng was widely recognized one of the pre-eminent traditional landscape artists of his generation and throughout the 1980’s and early 90’s was featured in national and international exhibitions of modern and contemporary Chinese painting at home in China and abroad. [5]

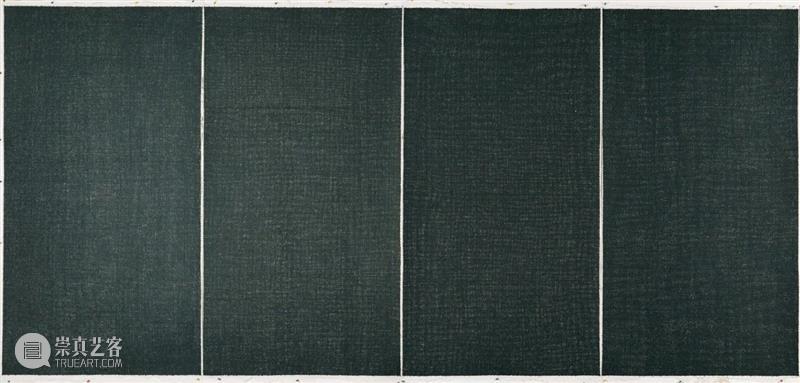

Li Huasheng, 0679, 2006, Ink on paper, 4 panels, 180 x 97 cm each panel

Li Huasheng, 0679 [detail], 2006, Ink on paper, 4 panels, 180 x 97 cm each panel

Li Huasheng described his travels in the United States as particularly liberating and upon his return to China, he felt unable to continue painting in the traditional manner. Instead, living as a reclusive, he departed on regular and extended excursions into the Himalayas; Chinese landscape artists had never addressed these mountains as a subject and he felt drawn to their remoteness. During his travels, Li Huasheng frequently stayed overnight in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and woke, in the early hours, to the rhythmic sounds of the resident monks chanting their morning prayers. It then occurred to him that the way he would paint the landscape was not by depicting its outward form but by recording his state of mind while living amidst the mountains themselves.[3]

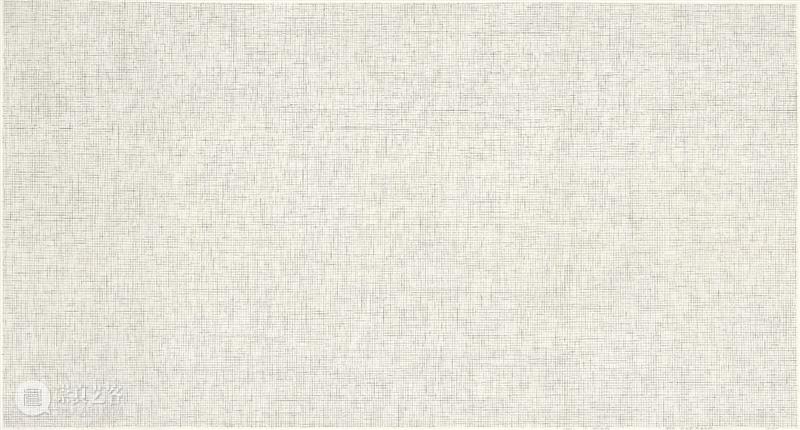

Li Huasheng traveling in the Himalayan Mountains, 2014

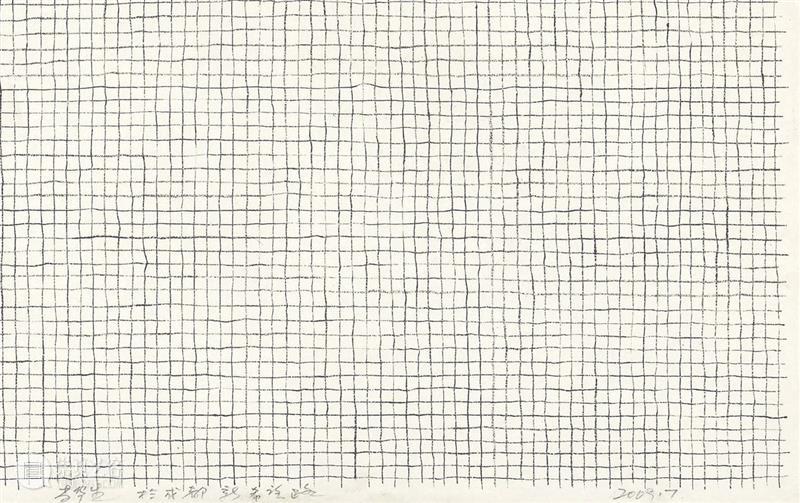

By 1998, this insight led Li Huasheng to develop an entirely novel, unprecedented practice as an ink artist: while in a disciplined, meditative state, Li Huasheng hand-limned vast grids of horizontal and vertical lines. Each hand-brushed line captured and recorded the moment-by-moment state of his body, perceptions, feelings, emotions and thoughts. Holding the brush as only a painter trained through decades of practice is able, Li Huasheng deployed each line in a state of meditative concentration, so that any minor fluctuations are directly attributable to fluctuations in qi, or the vital energy of his body and mind. [3]

Li Huasheng, 0097, 2009, Ink on paper, 95 x 178 cm

Li Huasheng, 0097 [detail], 2009, Ink on paper, 95 x 178 cm

This practice occupied him for the next twenty years and led to radical transformations in his contemporaneous landscape painting practice culminating in an iconic series of one-stroke paintings.

Li Huasheng, 0824, 2008, Ink on paper, 53 x 234 cm

Eastern Modernisms

The curatorial impetus for this exhibition began with Li Huasheng who, throughout the latter half of his career, expressed a keen interest in the modern calligraphic works of Inoue Yūichi. Inoue’s modern calligraphy was and still is frequently compared to the oil paintings of Abstract Expressionists such as Franz Kline.[2] Similarly, Li Huasheng’s abstract grid paintings have been compared to the minimalist grid paintings of Kline’s contemporary Agnes Martin. Such East-West framings are what Eugenia Bogdanova-Kummer calls “false friends” or false cognates: on the surface there appears to be a connection, but in reality, the two—Inoue and Kline; Li and Martin—are completely different artistically and conceptually.

Instead, Li Huasheng’s interest in Inoue’s practice prompts us to reconsider how we think about brush and ink as a medium and as a language for art making—not in terms of ink is Eastern and therefore traditional and other media are Western and therefore modern or contemporary—but in terms grounded in the historic, East Asian discourse on the brush-and-ink arts—calligraphy in the case of Inoue and landscape painting in the case of Li Huasheng—and in terms cognizant that plural modernisms of global importance may arise anywhere a regional discourse—such as the Bokujinkai modern calligraphy movement in Postwar Japan and the contemporary ink movement in post-Cultural-Revolution China—asserts a compelling, international influence.

Buddhism and Art

Intriguingly, both artists openly acknowledged the influence of Buddhism in the development of their art—Inoue Yūichi by a form of Modernist Zen which exerted a tremendous influence on art of the Postwar period both inside Japan and throughout the rest of the world and Li Huasheng by the Chan thought endemic to literati thinkers and artists since the Six Dynasties inflected by the esoteric Buddhism practiced in the temples of his native Sichuan and neighboring Tibet.

The influence of Modernist Zen thinkers such as D.T. Suzuki on not just the Abstract Expressionist painters in New York but on Postwar artists worldwide working in media synonymous with contemporary art practice —such as the ready-made, installation, performance, light-and-space, sound, concrete poetry and land art—has been well documented in major exhibitions and publications by instituttions such as the New York Guggenheim. [4]

In East Asia, however, the connection between Buddhism and the arts is not a new phenomenon but a very old one beginning with the introduction of Buddhist principles—through trade and religious exchange along the Silk Road—into the aesthetics of the Six Dynasties (220–589). The introduction of calligraphy to Japan from China in the 6th century was inseparably influenced by the subsequent transmissionof Buddhism, particularly Chan/Zen Buddhism from Tang Dyansty (618–907) China to Nara (710–794) and Heian (709–1185) period Japan. Painting in China, particularly literati painting, was also inseparable from Chan as almost every major development in the theory and practice of literati ink painting was precipitated by artists—Wang Wei (699–759) of the Tang, Su Shi (1037–1101) of the Song (960–1279) and Dong Qichang (1555–1636) of the Ming (1368–1644)—who were deeply learned in and influenced by Chan thought.

Inriguingly, although both artists purport to draw inspiration from Buddhism, Inoue’s calligraphic line and Li Huasheng’s painterly line couldn’t be more different:

Time dimension. Whereas Inoue Yūichi expands the capacity of his medium to capture dynamic and sometimes sudden changes in brush direction, speed, pressure, and angle, Li Huasheng radically reduces and simplifies the dynamic range of his brushwork so that within a single work, his brushwork appears at first never to change. If a line’s time-dimension records a process, Inoue’s is a discrete, dynamic event—like a shout—and Li Huasheng’s is a subtle, unbroken, sometimes oscillating, recurring action—like breathing.

Inoue Yūichi, Haha [Mother], 1961, Ink on Japanese paper, 131.5 x 141.5 cm

Li Huasheng, 1231 [detail], 2012, Ink on paper, 69.5 x 137 cm

Expressive dimension. While Inoue Yūichi simplifies form through his focus on a single, linguistic symbol, Li Huasheng abandons form and the expression of meaning through image or metaphor altogether. Whereas Inoue’s focus on a single word shifts our attention from history and classical scripture to a single idea and our personal experience, Li Huasheng’s line no longer depicts form, rather it becomes form itself; it doesn’t express—through human symbol, image or metaphor—rather, it records naturally and directly his heart-mind void of any object, image or form.

Human dimension. Whereas Inoue Yūichi’s calligraphic line captures his personality and inspiration with unprecedented rawness and freedom, Li Huasheng’s processual line records his heart-mind and body engaged in an unfolding act of self-discipline. Although his heart-mind is emphatically present and its intent focused and clear, Li Huasheng’s personality, unliked Inoue’s, is undetectable, sublimated.

Inoue Yūichi never claimed to be enlightened or to practice Zen. Rather, it was the Zen scholars who found in his art parallels with Zen principles. Similarly, Li Huasheng never claimed to be a Buddhist or to practice Buddhist meditation. Nevertheless, he did admit that his grid painting process might share some parallels with Buddhist cultivation practices. That Buddhism has provided inspiration for artists throughout history and into today has been established beyond question. But can art, in turn, provide us with insight into the nature of the Buddhist path? Or perhaps even serve as a path of enlightened self-cultivation in and of itself?

INKstudio, Shibunkaku and the Li Huasheng Art Foundation are honored to present the works of these two great masters in dialog on the contemporary expression of the classical East Asian brush-and-ink arts of calligraphy and painting and their importance to East Asian and international notions of modernity and contemporaneity, and to both classical and contemporary practices of self cultivation and spiritual enlightenment.

Sources

[1] Akimoto, Yuji. A Yu-Ichi Inoue Retrospective: 1955–1985. Tokyo: Kamimori Foundation, 2016.

[2] Bogdanova-Kummer, Eugenia. Bokujinkai: Japanese Calligraphy and the Postwar Avant-Garde. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 2020.

[3] Erickson, Britta. “Li Huasheng: He Swallows in All the Great Wilderness . . . He Becomes Wildly Free.” Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 17, No. 3: 48–57.

[4] Munroe, Alexandra. The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860–1989. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2009.

[5] Silbergeld, Jerome and Gong Jisui. Contradictions: Artistic Life, the Socialist State, and the Chinese Painter Li Huasheng. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1993.

For all media inquires (Chinese, English) please contact yang.fan@inkstudio.com.cn

For all other inquiries:

Inoue Yūichi sales (Japanese, Chinese, English): artfair@shibunkaku.co.jp

Li Huasheng sales (Chinese, English): xu.xu@inkstudio.com.cn

Curatorial (Japanese): artfair@shibunkaku.co.jp

Curatorial (English): yee.craig@inkstudio.com.cn

Curatorial (Chinese): yang.fan@inkstudio.com.cn

INKstudio, Beijing, China

www.inkstudio.com.cn

INK Studio is an art gallery based in Beijing. Its mission is to present Chinese experimental ink as a distinctive contribution to contemporary transnational art-making in a closely-curated exhibition program supported by in-depth critical analysis, scholarly exchange, bilingual publishing, and multimedia production. Representing more than 13 artists, including Bingyi, He Yunchang, Peng Kanglong, Li Jin, Li Huasheng, Wang Dongling, Wang Tiande, Yang Jiechang, and Zheng Chongbin, the gallery exhibits works of diverse media, including painting, calligraphy, sculpture, installation, performance, photography, and video. Since its inception in 2012, INK Studio has regularly appeared at art fairs such as the Armory Show (New York), Art Basel Hong Kong, and West Bund Art & Design (Shanghai) and placed works into major public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, and M+, Hong Kong.

Dr. Britta Erickson, INK Studio’s Artistic Director, drives all aspects of its programming and scholarly activities. An independent scholar and curator living in Palo Alto, California, she has curated major exhibitions at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington, D.C. (Word Play: Contemporary Art by Xu Bing) and the Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford (On the Edge: Contemporary Chinese Artists Encounter the West). In 2007 she co-curated the Chengdu Biennial, which focused on ink art, and in 2010 she was a contributing curator for Shanghai: Art of the City (Asian Art Museum, San Francisco). Dr. Erickson has written numerous books, articles, and essays on contemporary Chinese art. She has produced a series of short films about ink painting entitled The Enduring Passion for Ink. Ms. Erickson is on the advisory boards of The Ink Society (Hong Kong) and Three Shadows Photography Art Centre (Beijing), as well as the editorial boards of Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art and ART Asia Pacific. In 2006 she was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to conduct research in Beijing on the Chinese contemporary art market. Dr. Erickson received her Ph. D. in Chinese Art History from Stanford University

Shibunkaku, Kyoto, Japan

www.shibunkaku.co.jp

Shibunkaku was established in Kyoto in 1937 as one the of foremost dealers of classical and modern ink painting and calligraphy in Japan. Drawing upon the arts and culture of the former imperial capital, Shibunkaku has developed a unique gallery program that spans cultural and geographical borders, periods and genre. Specializing in early modern and modern Japanese fine art with an emphasis on calligraphy and painting, Shibunkaku has expanded its program to include postwar and contemporary art including the post-war modernist calligraphers Inoue Yūichi and Morita Shiryu, post-war abstract ceramicists of the Sodeisha movement and contemporary artists working in the traditional media of ink, ceramics, glass and bronze.

Shibunkaku’s gallery program is based on extensive scholarly research and, in addition to its own publications, supports the research, publishing and exhibition programming of academic institutions and museums both locally in Japan and internationally. Shibunkaku was a lender and contributor to the retrospective exhibition A Centennial Exhibition Inoue Yūichi at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa (2016) and Yuichi Inoue: Bell Tolls from Japan at the Tsinghua University Art Museum in Beijing (2020-2021) and a supporter of and contributor to Professor Eugenia Bogdanova-Kummer’s monograph Bokujinkai: Japanese Calligraphy and the Postwar Avant-Garde (2021).

The Li Huasheng Art Foundation, Seattle, WA, USA

The Li Huasheng Art Foundation was established in 2018 and endowed by the artist Li Huasheng. The Foundation is a Public Benefit Nonprofit Foundation organized and operated exclusively for charitable purposes. Its mission is to advance ink as a medium, language and means of expression in the visual arts. The Foundation pursues its public mission through a Public Collection of contemporary ink artwork for use by artists, scholars, researchers, universities and museums; Scholarly Research on the field of ink art and its contemporary practice; Public Exhibitions of modern and contemporary ink art for the general public; and Documentary Books and Media on the topic of ink art and its contemporary practice by living artists.

The Foundation is currently organizing a major museum retrospective exhibition of Li Huasheng’s artwork, publishing a academic monograph on Li Huasheng’s artistic career and compiling a catalogue raisonné for the artist.

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享