【展覽專文】喬治‧肖—歷史片斷 George Shaw—A Scrap of History

![]() {{newsData.publisher_name}}

{{newsData.update_time}}

浏览:{{newsData.view_count}}

{{newsData.publisher_name}}

{{newsData.update_time}}

浏览:{{newsData.view_count}}

来源 | {{newsData.source}} 作者 | {{newsData.author}}

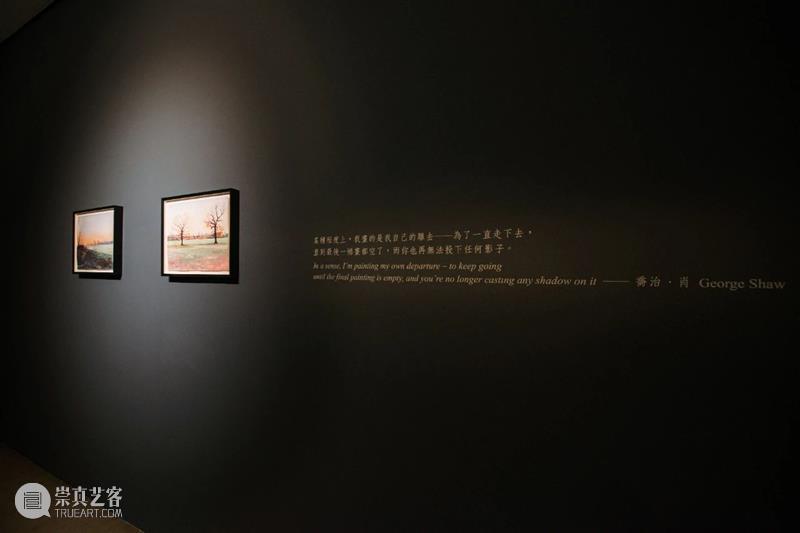

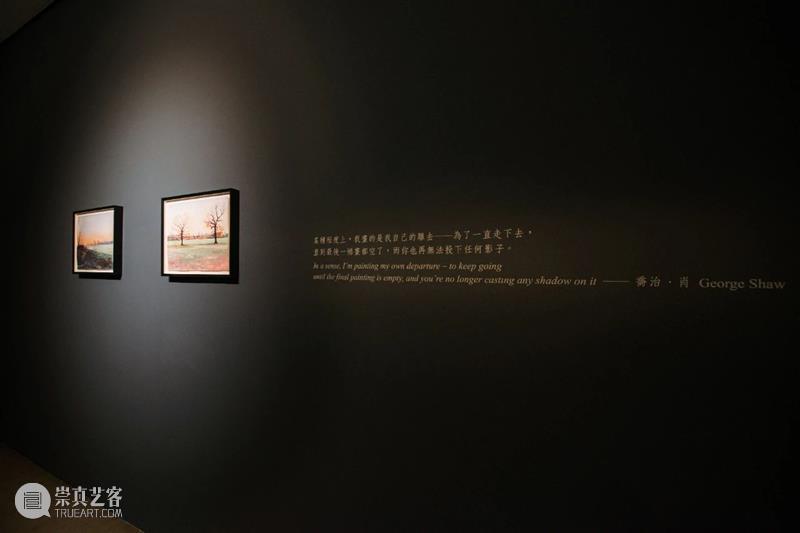

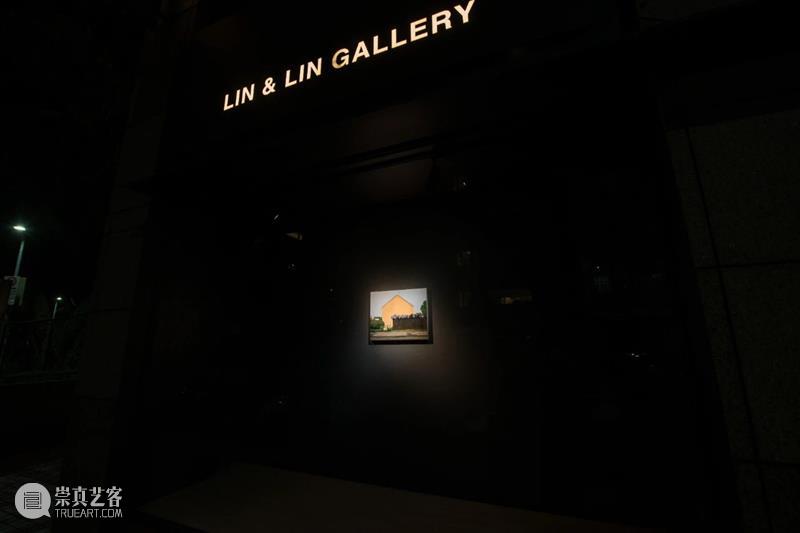

George Shaw—A Scrap of History策展人 Curators |Eli Zagury & Tamar Arnon展期 Dates|2021.09.04 - 10.09地點 Venue|大未來林舍畫廊 Lin & Lin Gallery

大未來林舍畫廊很榮幸於九月呈獻英國當代藝術家喬治‧肖(George Shaw)於亞洲首次個展《歷史片斷 A Scrap of History》。喬治‧肖2011年獲英國透納獎(Turner Prize)提名,並於2011年在英國BALTIC當代藝術中心、2016年在英國國家美術館(The National Gallery)舉辦個展。本次將展出藝術家琺瑯漆系列的全新創作,並透過肖筆下的英國市郊,引領我們在那些看似空寥,卻仍影影綽綽的風景中,踏上一段令人醉心,同時也侷促不寧的旅程。Lin & Lin Gallery is honored to present British Contemporary artist George Shaw's first solo exhibition in Asia, “A Scrap of History.” George Shaw was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2011 and held solo exhibitions at the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art in the UK in 2011 and at The National Gallery in 2016. This exhibition will showcase the artist's latest enamel paints series of works. The scenes of English suburbs painted by Shaw are devoid of people and bleak, but they are very much implicated in each painting. Through that, we, the audience are invited to be involved in a fascinating, yet unsettling journey.The paintings of George Shaw喬治‧肖(George Shaw)前陣子告訴我,有人說他的畫作總是「不見人影」,這樣的評論讓他感到不可思議:「我還覺得我作品裡的人太多了。」[1]過去幾十年來,透過繪畫、素描與攝影,他不斷重返同一個地方——位於考文垂(Coventry)邊陲,一處名為瓦丘(Tile Hill)的郊區—— 1970至80年代間,肖曾在此度過成長時期。雖然他的畫作中並未有人現身,但事實上,他們無所不在:正如那些最優秀的靜物畫一樣,總是令你感到某人才剛離開房間,或恰好流連於視線之外。儘管這些作品帶有一種凝止的氛圍,其中的時間感卻顫悠悠地打轉於現在和過去之間的某個點上—— 這真是再適切不過了。一如大多數的人,肖「總是想著過去發生的事」,即便他聲稱自己回憶過往的能力「相當薄弱」[2]。這點不只是他:有人就認為記憶交織了事實與虛構、佚失與渴望,因此並不可靠(套句俄國俗諺:「他的謊言說得好像親眼所見。」)要釐清發生過的歷史,是件難以招架的事。各式各樣—— 視覺的、語言的、聽覺的、情感的,以及,姑且美其名之為,精神的——線索令人應接不暇,無法僅用某種特定的方式統一處理。也因此,肖的作品中,那些模糊不定、在畫面上忽隱忽現卻又看似無關緊要的細節,恰恰指出,我們所見到的遠不只是眼前事物的集結。George Shaw recently told me how startled he was when someone commented on the absence of people in his painting. ‘I think there are too many in them,’ he said.[1]For the past few decades, he has returned again and again – via paintings, drawings and photographs – to Tile Hill, the council estate where he grew up on the edge of Coventry in the 1970s and ’80s. While people are not physically present in these pictures, they are, in truth, everywhere: as in the best still life paintings, it’s as if someone has just left the room or wandered out of shot.Despite their aura of stillness, the sense of time in Shaw’s paintings trembles at a point between the present and long ago. This is apt. Like most people, the artist is ‘always thinking about things that happened in the past’ although he describes his powers of recollection as ‘weak and thin’.[2]He’s not alone: few would argue that memory is fallible, a fusion of fact and fiction, loss and longing. (A Russian proverb: ‘he lied like an eye witness’.) Trying to make sense of our history is overwhelming. There are simply too many prompts– visual, verbal, aural, emotional and, for want of a better word, spiritual –to respond to it in a singular manner. As a result, seemingly inconsequential details surface and recede in Shaw’s work with an ambiguity and uncertainty that indicates that we are seeing is more than the sum of their physical parts. 關於這點,肖的說法是:「我畫鬼魂」。[3]然而,他的創作卻無法這麼一言以蔽之。畫家相信,雖然我們都被過去所糾纏,但在同時,我們更常成為那個糾纏者。幾年前,肖的母親過世,一家人最後一次搬離了居處。肖笑著道,「我們在那裡所度過的四十年光陰,可能正糾纏著現在住在裡面的人。我是出沒在他們生活中作祟的鬼魂,但他們卻一無所知。」不過他跟著解釋,與其說死後的生命是陰氣森森的魅影,不如說那是一段具有現實溫度的經歷。「我一直覺得,如果你不相信有鬼魂,那你應該也無法相信網路或書或音樂或藝術。人類歷史就是其一切的紀錄。」這話多少暗示著,我們的身體就是一具記錄器:帶有缺陷且反覆出現失誤的記憶裝置。肖用無數的手法來挖掘過往的線索,或許這也代表著,時間本身並不如我們所深信的那般直來直往。它既複雜又矛盾、曲曲折折又無始無終,活靈活現的賦予當下生命,讓我們不需移動分毫,就能在歲月間穿梭自如。對肖而言,攝影是「單程的時光之旅」,而繪畫——因為並不那麼依賴真實性——則是「將影像從時態中解放」。說白了,他認為繪畫這種紀錄方式,不僅記下他在這個世界所到之處的足跡,同時也記下他對於這趟旅行的看法。正如他寫給我的信中說道:「所有這些影像都是歷史的碎片,就像那些被我拋諸腦後的事物——無論繪畫還是髒內褲——也像我的身體,它不僅是我自己,也是我自己的故事。」[4]Sunrise Over the Ponderosa, 2021, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 90x120 cm.Shaw describes his approachas: ‘I paint ghosts’.[3]It’s not, however, as clear-cut an activity as it might sound. The artist believes that while we’re haunted by the past, we are also, more often than not, the haunters. When his mother died a few years ago, the family left their home for the last time. Shaw tells me, laughing, that ‘our presence in that house for 40 years will be haunting the people there now. I am an active ghost in their life and they’re not aware of it.’ He explained, though, that his concept of the afterlife is less spooky than it is empirical. ‘I always think that if you don’t believe in ghosts then you don’t believe in the internet or in books or music or art. The history of the human race is one of recording.’ The implication lingers that our bodies themselves are recording devices: imperfect memory machines that repeatedly malfunction.The myriad ways in which Shaw mines the past hints at the possibility that time itself is not as straightforward as we’ve been led to believe. It’s complicated and contradictory, pliable and cyclical, an active animator of the present that allows us to slip easily between the years without going anywhere. Unlike photography, which Shaw describes as ‘time travel in one direction’, painting, less rooted inveracity, ‘liberates the image from its tense’. Bluntly put, painting, for Shaw, is a way of recording where he has been in the world–and what he thinks about that journey now. As he wrote to me: ‘All these images are scraps of history, as are the things I leave behind me whether they are paintings or dirty underpants, just as I am myself and my own story.’[4]

關於這點,肖的說法是:「我畫鬼魂」。[3]然而,他的創作卻無法這麼一言以蔽之。畫家相信,雖然我們都被過去所糾纏,但在同時,我們更常成為那個糾纏者。幾年前,肖的母親過世,一家人最後一次搬離了居處。肖笑著道,「我們在那裡所度過的四十年光陰,可能正糾纏著現在住在裡面的人。我是出沒在他們生活中作祟的鬼魂,但他們卻一無所知。」不過他跟著解釋,與其說死後的生命是陰氣森森的魅影,不如說那是一段具有現實溫度的經歷。「我一直覺得,如果你不相信有鬼魂,那你應該也無法相信網路或書或音樂或藝術。人類歷史就是其一切的紀錄。」這話多少暗示著,我們的身體就是一具記錄器:帶有缺陷且反覆出現失誤的記憶裝置。肖用無數的手法來挖掘過往的線索,或許這也代表著,時間本身並不如我們所深信的那般直來直往。它既複雜又矛盾、曲曲折折又無始無終,活靈活現的賦予當下生命,讓我們不需移動分毫,就能在歲月間穿梭自如。對肖而言,攝影是「單程的時光之旅」,而繪畫——因為並不那麼依賴真實性——則是「將影像從時態中解放」。說白了,他認為繪畫這種紀錄方式,不僅記下他在這個世界所到之處的足跡,同時也記下他對於這趟旅行的看法。正如他寫給我的信中說道:「所有這些影像都是歷史的碎片,就像那些被我拋諸腦後的事物——無論繪畫還是髒內褲——也像我的身體,它不僅是我自己,也是我自己的故事。」[4]Sunrise Over the Ponderosa, 2021, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 90x120 cm.Shaw describes his approachas: ‘I paint ghosts’.[3]It’s not, however, as clear-cut an activity as it might sound. The artist believes that while we’re haunted by the past, we are also, more often than not, the haunters. When his mother died a few years ago, the family left their home for the last time. Shaw tells me, laughing, that ‘our presence in that house for 40 years will be haunting the people there now. I am an active ghost in their life and they’re not aware of it.’ He explained, though, that his concept of the afterlife is less spooky than it is empirical. ‘I always think that if you don’t believe in ghosts then you don’t believe in the internet or in books or music or art. The history of the human race is one of recording.’ The implication lingers that our bodies themselves are recording devices: imperfect memory machines that repeatedly malfunction.The myriad ways in which Shaw mines the past hints at the possibility that time itself is not as straightforward as we’ve been led to believe. It’s complicated and contradictory, pliable and cyclical, an active animator of the present that allows us to slip easily between the years without going anywhere. Unlike photography, which Shaw describes as ‘time travel in one direction’, painting, less rooted inveracity, ‘liberates the image from its tense’. Bluntly put, painting, for Shaw, is a way of recording where he has been in the world–and what he thinks about that journey now. As he wrote to me: ‘All these images are scraps of history, as are the things I leave behind me whether they are paintings or dirty underpants, just as I am myself and my own story.’[4]

憑著法醫學者般的一絲不苟,肖了解到,記憶的精準再現取決於細節:例如,灰色天空襯托著常綠樹木的獨特形狀與色澤,或是鄰居歪斜的煙囪,又或是空房中窗簾和暖氣之間的關係。話雖如此,記憶常會扭曲我們在心中所回想的重要關鍵,讓曾經知曉的事物變得陌生(佛洛伊德將「詭秘」(uncanny)一詞描述為「並非什麼新奇或外來的事物,而是原先在腦海中根深蒂固的某種熟悉,透過潛抑的過程而變得疏離」[5])。肖告訴我,他在離開一段時間之後重新造訪童年老家,想著眼前必定滄海桑田,但令人震驚的是一切如昔:「只有些草長了些,可能還有棵樹不見了。」

憑著法醫學者般的一絲不苟,肖了解到,記憶的精準再現取決於細節:例如,灰色天空襯托著常綠樹木的獨特形狀與色澤,或是鄰居歪斜的煙囪,又或是空房中窗簾和暖氣之間的關係。話雖如此,記憶常會扭曲我們在心中所回想的重要關鍵,讓曾經知曉的事物變得陌生(佛洛伊德將「詭秘」(uncanny)一詞描述為「並非什麼新奇或外來的事物,而是原先在腦海中根深蒂固的某種熟悉,透過潛抑的過程而變得疏離」[5])。肖告訴我,他在離開一段時間之後重新造訪童年老家,想著眼前必定滄海桑田,但令人震驚的是一切如昔:「只有些草長了些,可能還有棵樹不見了。」

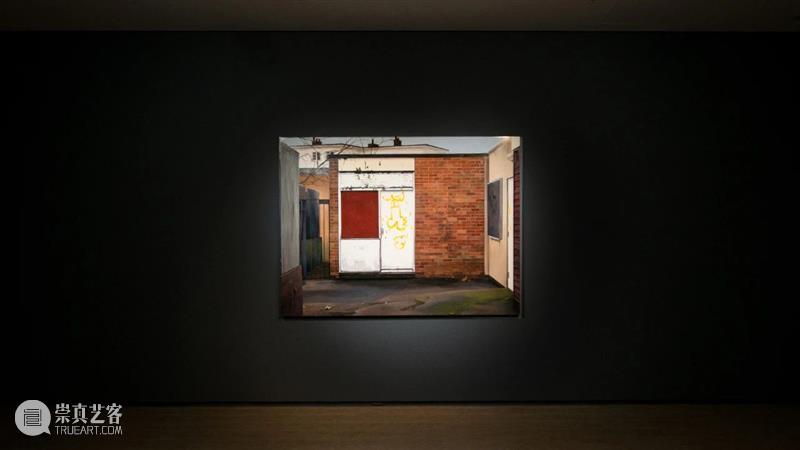

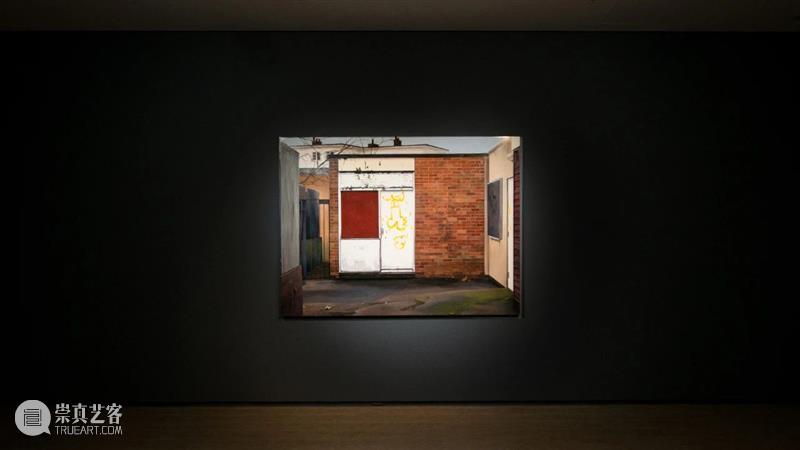

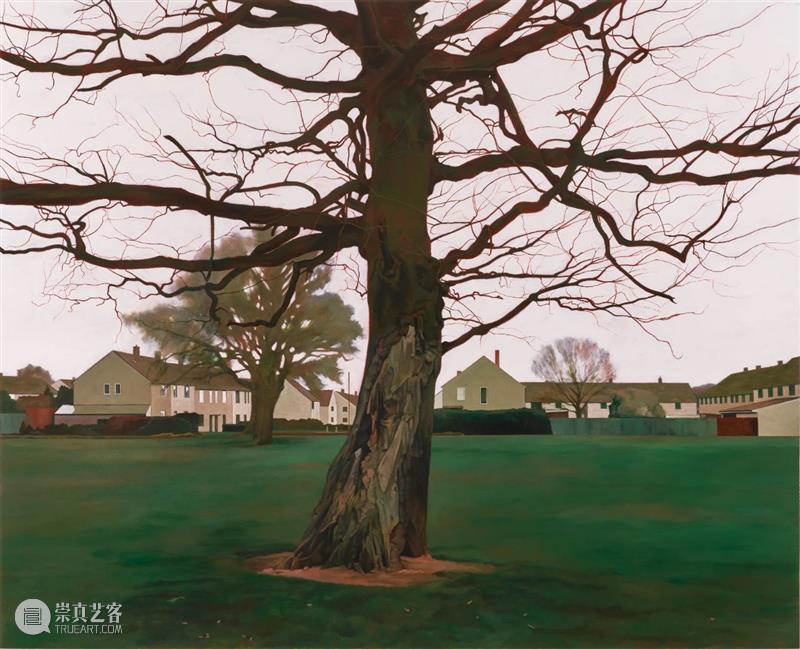

肖採用光滑的Humbrol琺瑯漆——一種比起所謂的藝術家,還更為模型迷所熟悉的媒材——細細地層層上色,藉此驅散他的回憶。肖說,每次被問到為何選用這種媒材時,他的答案都不一樣,但總的來說,他喜歡這種顏料的質地特性,及其暗含的可能隱喻。他解釋,「油彩乾的不是太快就是太慢」,而琺瑯漆則是一種「工人在車庫裡使用的」媒材(此外,「也被拿來繪製酒吧招牌」則是它另一個討喜的理由)。閃耀的光澤意味著顏料在乾燥後看來依舊濕潤——一種讓世界反身自照的性質。乍看之下,肖的畫面靜謐安詳,但觀察越久,景物就越發喧嘩。敘事的片段像電影劇照一樣積累:田野中一顆幽明如月的足球;紅磚牆上將就漆成的藍色球門;銀光粼粼的水坑——你幾乎就要聽到一位母親呼喚孩子回家晚餐,聽到遠方隱約的車水馬龍,也聽到突降陣雨的稀哩嘩啦。肖喜歡透過講故事,將原本對當代藝術無感的觀眾帶進來。他告訴我,雖然他的創作主調比較接近山謬‧貝克特(Samuel Beckett)所謂的「沒有演員的戲劇」,但他真正想做的是「在流行音樂的生態裡佔據一個位置」然後以「一首歌或一齣肥皂劇」的日常用語進行溝通。肖之所以決定專注於他的童年主題,部分的原因是出自他稱之為「對大腦運動的抗拒」,以及,用「感性、鄉愁與情感」繪畫的需求。他希望能創造出一種「幫你撐過一整天」的藝術形式。The Suburbian, 2018-2021, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 90x120 cm.With the scrupulousness of a forensic scientist, Shaw understands that an accurate recreation of a memory is dependent on its details: in, say, the very particular shape and shade of an evergreen tree against a grey sky or the wonky curve of a neighbour’s chimney or in the relationship between the curtains and a radiator in an empty room. That said, memory often distorts the significant places we mentally revisit and what was once recognisable is rendered strange. (Sigmund Freud described the ‘uncanny’ as ‘nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression.’[5])Shaw tells me that when he returned to his childhood home after some time away, he assumed it would look radically different, but the shocking thing was, nothing had changed: ‘some grass was longer and maybe a tree had gone.’The artist exorcises his memories with a meticulous build-up of glossy Humbrol enamel paint – a medium more familiar to model makers than so-called fine artists. Shaw says that his reasons for using it change every time he’s asked, but, generally speaking, he likes it as much for its metaphorical potential as its physical properties. He explains that whereas ‘oil paint dries too fast and too slow’, enamel is a medium ‘used by working-class men in sheds’. (The fact that it’s ‘also used to paint pub signs’ is another mark in its favour.) Its high gloss also means that even when it’s dry it still looks wet – a quality that ‘reflects the world back on itself’.In Shaw’s paintings, scenes that at first seem quiet and contemplative become noisier the longer you observe them. Snippets of narratives accumulate like film stills: a football glowing like a moon amid afield; a crudely painted blue goal on a red brick wall; the silver sheen of a puddle – you can almost hear a mother calling her children in for dinner, the distant hum of traffic, the hiss of sudden rain. Shaw likes the idea that storytelling brings people in who might not otherwise be interested in contemporary art. He tells me that although his preoccupations are perhaps closer to Samuel Beckett’s ‘notion of a play without actors’ than anything else, he wants ‘to occupy the space of pop music’ and to communicate in the everyday language of ‘a song or a soap opera’. When Shaw decided to focus on his childhood as his subject, he was partly motivated by what he describes as ‘are jection of a cerebral process’ and a need to paint with ‘sentiment, nostalgia and emotion’. He wanted to create an art form that ‘helped get you through the day’. 儘管畫中瀰漫著濃稠的憂鬱氣息,肖的很多作品都帶有一種狡獪的幽默。除了向許多前輩藝術家的成就致敬之外,他也樂此不疲地藉由圖像與文字遊戲的結合戳破藝術史裝腔作勢的假面。例如,《大師》(The Old Master,2015-16)一作中畫了一棵樹,樹幹上塗鴉了一根火箭般昂揚的老二;在《古老鄉村》(The Old Country)裡,樹皮則像外陰一樣腫脹;而《情聖》(The Great Lover,2018)則是一幅習作,上面畫了一間青少年俱樂部暨社區活動中心的後門,門上信手塗抹了粗俗的射精漫畫。肖寫給我的信中是這麼提的:我一直深受這類塗鴉的吸引:直白、誠實、有趣、唐突……屬於一種非官方的野史。這幅作品在此展現的特別淋漓盡致,不只是一般陽具與睪丸,還有奶子和看上去很像陰部的圖樣,以及漫畫式的射精軌跡。如果它是法國洞窟裡的壁畫,或是白堊山坡上的線形圖像,那肯定會被好好保存下來。[6]同樣的,在《愛情學院》(The School of Love,2015-16)中,一個被棄置在灌木叢中的破舊紅棕條紋床墊,明顯暗喻著被打斷的親密行為。此作以標題呼應目前收藏於倫敦國家藝廊(National Gallery)的《維納斯、墨丘利與邱比特》(Venus with Mercury and Cupid ,年代約在1525);後者另外又名The School of Love,由義大利畫家安東尼奧‧達‧科雷吉歐( Antonio da Correggio)描繪了維納斯、墨丘利與邱比特一家三口赤條條的置身林中——從這點來看,我們可以說肖的《愛情學院》一脈相承了高雅與淫穢所混血的古老繪畫傳統。Survivors 1, 2020, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 123.5x152 cm.Despite their all-pervasive mood of melancholy many of Shaw’s paintings have a sly sense of humour. While in thrall to many of the achievements of long-dead artists, he also enjoys deflating the pomposities of art history via a combination of image and wordplay. The Old Master (2015-16), for example, is a picture of a tree graffitied with a cock as cheerful as a rocket. In The Old Country, the bark of a tree swells like a vulva and The Great Lover(2018) is a study of a door at the back of a youth club-cum-community building defaced with a crude cartoon of an ejaculation. Shaw wrote to me about the painting that:I’ve long been fascinated and drawn to this type of graffiti; explicit, honest, funny, offensive ... an unofficial history. This is a particularly elaborate example showing not only the usual cock and balls but also some boobs and what could be a hairy fanny and a comical ejaculatory trajectory. If it had been found in a French cave or on a chalk hillside it would be preserved.[6]Similarly, in The School of Love (2015-16) a tatty red-and-brown mattress is pictured propped up in a thick copse, the intimation of interrupted intimacy explicit. The painting – its title a nod to Antonio da Correggio’s depiction of a naked family in a wood, Venus with Mercury and Cupid (The School of Love) (c.1525), that hangs in London’s National Gallery – is part of a centuries-old lineage of paintings in which the elevated and the bawdy commingle.肖對藝術史的援引以及對日常語彙的著迷,不僅直接記錄了他的個人經驗,也遙指那些隨著時光流轉而改變意義的事件與物件。他曾說道:「象徵之美在於曖昧模糊。如果你要的是具體明確,那就別用象徵——改用符號。」在舉例時,他告訴我,小時候會覺得吊掛在樹上的鞦韆很好玩,但是近來,這個意象卻變得幽微晦暗,常讓他想起自殺的朋友。同樣的,在他的父母過世之後,肖繪製了兩幅大尺寸的《倖存者》(Survivors,2020),接著又畫了《日出西黃松》(Sunrise Over the Ponderosa,2021),透過作品重訪舊居屋前的兩棵樹,藉以緬懷已經過世的父母在他生命中所留下的回憶。他在給我的信中寫著:「我很清楚,這兩棵西黃松的創作,既是我對父母死亡的冥思,也是一段從喪親之痛緩慢復原的過程……我想要將它們呈現為紀念碑,一種超越時代的存在,如巨石般神秘而又毫無意義。」[7]時間的流失,無可避免地引領我們遭逢所愛之人的死亡。因此,肖的許多畫作彷彿一首傷悼的輓歌;或者沉浸在消逝的光芒中,或者暗示事物的破碎、散佚與創痛。在《受傷時刻》(Injury Time,2019)裡,一棵裂成兩半的樹幹,主宰了平凡郊區的街景。在《安養中心的日出》(Sunrise Over the Care Home,2018)裡,令人目眩神迷的天空如同新創的傷口一般鮮活;雖然太陽正在升起,對某些人來說卻剛好相反。近來,肖一直在畫他家房中空無一物的房間,藉著鉅細靡遺觀察窗簾、窗戶以及陽光在地板落下的陰影,細細咀嚼他的悲傷與失落。放眼今日,鮮少有藝術家能透過創作,如此清晰地闡明自小生活的所在是怎麼型塑一個孩子成年之後的樣貌。現年五十多歲的肖告訴我,他在13 至21歲之間為其創作做足了所有需要的功課。多年來攝影與自畫像的實驗,讓他領悟「我唯一能創作的主題,就是我的舊家和童年。」一次又一次畫著故居「成為我在模仿法蘭西斯.培根與林布蘭時,所能創作出最接近自畫像的東西。」(但矛盾的是,他也意識到「當我不再畫自己的臉時」,反而可以更精準地掌握自己。)瓦丘逐漸成為「一個充滿寓意的所在,讓我能於其中自由探索一切事物,從音樂、階級到種族」。說到底,這段探索本身就像謎一般的費解,重點不在結果,而在喚起一種心情,一種氛圍,一種場所感。正如他在一次訪談中所說的:「其中的寓意非關時間,而是正在流逝,以及,已經流逝的時間,你所看到的每個意象都標示著某條路上的某個景點,而在那裡,原本毫無意義的世俗的一切,都在瞬間變得,神秘起來。」[8]

儘管畫中瀰漫著濃稠的憂鬱氣息,肖的很多作品都帶有一種狡獪的幽默。除了向許多前輩藝術家的成就致敬之外,他也樂此不疲地藉由圖像與文字遊戲的結合戳破藝術史裝腔作勢的假面。例如,《大師》(The Old Master,2015-16)一作中畫了一棵樹,樹幹上塗鴉了一根火箭般昂揚的老二;在《古老鄉村》(The Old Country)裡,樹皮則像外陰一樣腫脹;而《情聖》(The Great Lover,2018)則是一幅習作,上面畫了一間青少年俱樂部暨社區活動中心的後門,門上信手塗抹了粗俗的射精漫畫。肖寫給我的信中是這麼提的:我一直深受這類塗鴉的吸引:直白、誠實、有趣、唐突……屬於一種非官方的野史。這幅作品在此展現的特別淋漓盡致,不只是一般陽具與睪丸,還有奶子和看上去很像陰部的圖樣,以及漫畫式的射精軌跡。如果它是法國洞窟裡的壁畫,或是白堊山坡上的線形圖像,那肯定會被好好保存下來。[6]同樣的,在《愛情學院》(The School of Love,2015-16)中,一個被棄置在灌木叢中的破舊紅棕條紋床墊,明顯暗喻著被打斷的親密行為。此作以標題呼應目前收藏於倫敦國家藝廊(National Gallery)的《維納斯、墨丘利與邱比特》(Venus with Mercury and Cupid ,年代約在1525);後者另外又名The School of Love,由義大利畫家安東尼奧‧達‧科雷吉歐( Antonio da Correggio)描繪了維納斯、墨丘利與邱比特一家三口赤條條的置身林中——從這點來看,我們可以說肖的《愛情學院》一脈相承了高雅與淫穢所混血的古老繪畫傳統。Survivors 1, 2020, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 123.5x152 cm.Despite their all-pervasive mood of melancholy many of Shaw’s paintings have a sly sense of humour. While in thrall to many of the achievements of long-dead artists, he also enjoys deflating the pomposities of art history via a combination of image and wordplay. The Old Master (2015-16), for example, is a picture of a tree graffitied with a cock as cheerful as a rocket. In The Old Country, the bark of a tree swells like a vulva and The Great Lover(2018) is a study of a door at the back of a youth club-cum-community building defaced with a crude cartoon of an ejaculation. Shaw wrote to me about the painting that:I’ve long been fascinated and drawn to this type of graffiti; explicit, honest, funny, offensive ... an unofficial history. This is a particularly elaborate example showing not only the usual cock and balls but also some boobs and what could be a hairy fanny and a comical ejaculatory trajectory. If it had been found in a French cave or on a chalk hillside it would be preserved.[6]Similarly, in The School of Love (2015-16) a tatty red-and-brown mattress is pictured propped up in a thick copse, the intimation of interrupted intimacy explicit. The painting – its title a nod to Antonio da Correggio’s depiction of a naked family in a wood, Venus with Mercury and Cupid (The School of Love) (c.1525), that hangs in London’s National Gallery – is part of a centuries-old lineage of paintings in which the elevated and the bawdy commingle.肖對藝術史的援引以及對日常語彙的著迷,不僅直接記錄了他的個人經驗,也遙指那些隨著時光流轉而改變意義的事件與物件。他曾說道:「象徵之美在於曖昧模糊。如果你要的是具體明確,那就別用象徵——改用符號。」在舉例時,他告訴我,小時候會覺得吊掛在樹上的鞦韆很好玩,但是近來,這個意象卻變得幽微晦暗,常讓他想起自殺的朋友。同樣的,在他的父母過世之後,肖繪製了兩幅大尺寸的《倖存者》(Survivors,2020),接著又畫了《日出西黃松》(Sunrise Over the Ponderosa,2021),透過作品重訪舊居屋前的兩棵樹,藉以緬懷已經過世的父母在他生命中所留下的回憶。他在給我的信中寫著:「我很清楚,這兩棵西黃松的創作,既是我對父母死亡的冥思,也是一段從喪親之痛緩慢復原的過程……我想要將它們呈現為紀念碑,一種超越時代的存在,如巨石般神秘而又毫無意義。」[7]時間的流失,無可避免地引領我們遭逢所愛之人的死亡。因此,肖的許多畫作彷彿一首傷悼的輓歌;或者沉浸在消逝的光芒中,或者暗示事物的破碎、散佚與創痛。在《受傷時刻》(Injury Time,2019)裡,一棵裂成兩半的樹幹,主宰了平凡郊區的街景。在《安養中心的日出》(Sunrise Over the Care Home,2018)裡,令人目眩神迷的天空如同新創的傷口一般鮮活;雖然太陽正在升起,對某些人來說卻剛好相反。近來,肖一直在畫他家房中空無一物的房間,藉著鉅細靡遺觀察窗簾、窗戶以及陽光在地板落下的陰影,細細咀嚼他的悲傷與失落。放眼今日,鮮少有藝術家能透過創作,如此清晰地闡明自小生活的所在是怎麼型塑一個孩子成年之後的樣貌。現年五十多歲的肖告訴我,他在13 至21歲之間為其創作做足了所有需要的功課。多年來攝影與自畫像的實驗,讓他領悟「我唯一能創作的主題,就是我的舊家和童年。」一次又一次畫著故居「成為我在模仿法蘭西斯.培根與林布蘭時,所能創作出最接近自畫像的東西。」(但矛盾的是,他也意識到「當我不再畫自己的臉時」,反而可以更精準地掌握自己。)瓦丘逐漸成為「一個充滿寓意的所在,讓我能於其中自由探索一切事物,從音樂、階級到種族」。說到底,這段探索本身就像謎一般的費解,重點不在結果,而在喚起一種心情,一種氛圍,一種場所感。正如他在一次訪談中所說的:「其中的寓意非關時間,而是正在流逝,以及,已經流逝的時間,你所看到的每個意象都標示著某條路上的某個景點,而在那裡,原本毫無意義的世俗的一切,都在瞬間變得,神秘起來。」[8]

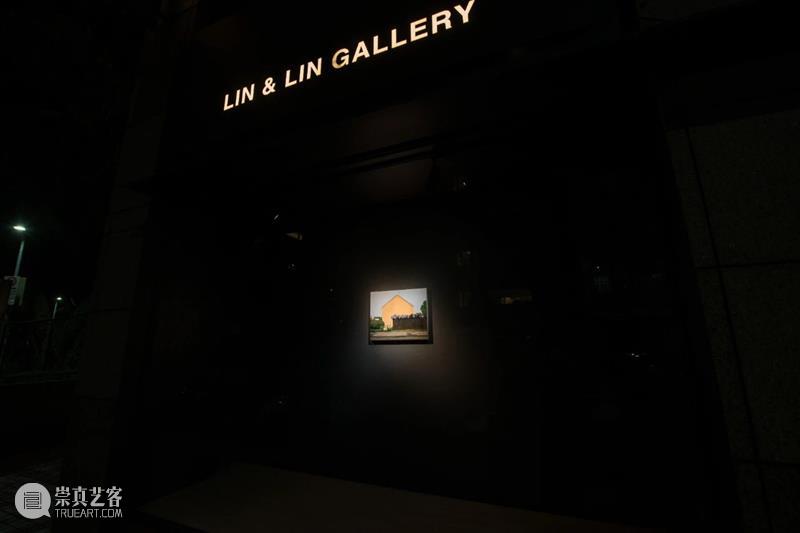

Short Loved, 2020, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 43x53 cm.Shaw’s art-historical references and his fascination with vernacular languages are at once a record of his direct experience and allusions to incidents and objects that shift in meaning as the years go by. He explained: ‘The beauty of symbols is that they are vague. If you want to be specific don’t use a symbol – use a sign.’ As an example, he told me that whereas a swing that hung off a tree was exciting when he was a child, in recent years, it assumes a darker meaning, recalling friends who have taken their own lives. Similarly, since his parents died, two large paintings called ‘Survivors’ from 2020, and then Sunrise Over the Ponderosa(2021), revisit two trees in front of his family home which have become something of a memorial to the presence of his late parents in his life. He wrote to me that: ‘I don’t think it takes too much effort for me to see my focus on the two Ponderosa trees as a meditation on the deaths of my mum and dad and the slow removal of myself from the scene … I wanted to show the trees as monuments, as something dragged from one age to another and as mysterious and meaningless as megaliths.’[7]The passing of time inevitably involves the death of people we love. As a result, many of Shaw’s paintings feel elegiac, soaked in an atmosphere of dying light or the intimation of something broken, lost or wounded. In Injury Time (2019) a tree, its trunk split in two, dominates the view of a bland suburban street. In Sunrise Over the Care Home (2018), the hallucinogenic sky is as vivid as a fresh wound; although the sun is coming up, it’s obviously setting for some. Of late, the artist has been drawing the empty rooms of his family home, dealing with his grief and loss by scrutinising the curtains and windows and how the sunlight casts shadows across the floor.There are few artists working today who illustrate so well that the place where a child grows up shapes the adult he or she is to become. Now in his fifties, Shaw told me that he did all of the research he needs for his work between the ages of 13 and 21. After years of experimenting with photography and self-portraiture, he realised that ‘making a painting of my family house and my childhood was the only subject I had.’ Painting his family home again and again ‘became something closer to self-portraiture than anything I could have imagined when I was apeing Francis Bacon and Rembrandt.’(Paradoxically, he realised he could render himself more accurately ‘when I stopped painting my face’.) Tile Hill gradually became ‘an allegorical place where I could explore everything from music to class to race.’ But ultimately, the exploration is an enigmatic one, less about conclusions than about an evocation of a mood, a feeling, a sense of place. As he put it in one interview: ‘The allegory is not of time, but of time passing, of time having passed, and each image marks a point in a road where the mundane and the meaningless become briefly mysterious.’[8]

Short Loved, 2020, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 43x53 cm.Shaw’s art-historical references and his fascination with vernacular languages are at once a record of his direct experience and allusions to incidents and objects that shift in meaning as the years go by. He explained: ‘The beauty of symbols is that they are vague. If you want to be specific don’t use a symbol – use a sign.’ As an example, he told me that whereas a swing that hung off a tree was exciting when he was a child, in recent years, it assumes a darker meaning, recalling friends who have taken their own lives. Similarly, since his parents died, two large paintings called ‘Survivors’ from 2020, and then Sunrise Over the Ponderosa(2021), revisit two trees in front of his family home which have become something of a memorial to the presence of his late parents in his life. He wrote to me that: ‘I don’t think it takes too much effort for me to see my focus on the two Ponderosa trees as a meditation on the deaths of my mum and dad and the slow removal of myself from the scene … I wanted to show the trees as monuments, as something dragged from one age to another and as mysterious and meaningless as megaliths.’[7]The passing of time inevitably involves the death of people we love. As a result, many of Shaw’s paintings feel elegiac, soaked in an atmosphere of dying light or the intimation of something broken, lost or wounded. In Injury Time (2019) a tree, its trunk split in two, dominates the view of a bland suburban street. In Sunrise Over the Care Home (2018), the hallucinogenic sky is as vivid as a fresh wound; although the sun is coming up, it’s obviously setting for some. Of late, the artist has been drawing the empty rooms of his family home, dealing with his grief and loss by scrutinising the curtains and windows and how the sunlight casts shadows across the floor.There are few artists working today who illustrate so well that the place where a child grows up shapes the adult he or she is to become. Now in his fifties, Shaw told me that he did all of the research he needs for his work between the ages of 13 and 21. After years of experimenting with photography and self-portraiture, he realised that ‘making a painting of my family house and my childhood was the only subject I had.’ Painting his family home again and again ‘became something closer to self-portraiture than anything I could have imagined when I was apeing Francis Bacon and Rembrandt.’(Paradoxically, he realised he could render himself more accurately ‘when I stopped painting my face’.) Tile Hill gradually became ‘an allegorical place where I could explore everything from music to class to race.’ But ultimately, the exploration is an enigmatic one, less about conclusions than about an evocation of a mood, a feeling, a sense of place. As he put it in one interview: ‘The allegory is not of time, but of time passing, of time having passed, and each image marks a point in a road where the mundane and the meaningless become briefly mysterious.’[8]

本文作者Jennifer Higgie為旅居英國倫敦的澳洲作家,曾於frieze雜誌擔任編輯,目前為自由撰稿人,並於播客節目《Bow Down》擔任主持,討論藝術史中的女性。作者同時也為童書《There’s Not One》的作者暨繪者;《The Artist’s Joke》的編輯與小說《Bedlam》的作者。其關於女性自畫像的新書《The Mirror & The Palette》已由Weidenfeld & Nicolson出版發行。她同時也為一劇作家。

Jennifer Higgie is an Australian writer who lives in London. Previously the editor of frieze magazine, she is now editor-at-large and the presenter of Bow Down, a podcast about women in art history. She is the author and illustrator of the children’s book There’s Not One; the editor of The Artist’s Joke and author of the novel Bedlam. Her new book on women’s self-portraits, The Mirror & The Palette, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson. She also writes screenplays.[1] 除非特別註明,否則所有的引言均來自筆者與喬治‧肖(George Shaw)於2021年2月22日在Zoom上面的對話。[2] 引自The Art Newspaper podcast:班‧路克(Ben Luke)與喬治‧肖於2019年2月8日的對話。[4] 筆者與肖於2021年2月21日的電子郵件。[5] 此定義引自倫敦佛洛伊德博物館:https://www.freud.org.uk/2019/09/18/the-uncanny/[8] 與德米崔‧帕帕洛尼(Demetrio Paparoni)於2021年1月17 日在《明日》(Domani)上的訪談。[1] Unless otherwise mentioned, all quotes from zoom conversation between the author and George Shaw, 22 February 2021[2] Quotes from this paragraph from The Art Newspaper podcast: Ben Luke in conversation with George Shaw, 8 February 2019[3] Ibid

[4] Email from George Shaw to the author, 21 February 2021

[5] Definition cited by the Freud Museum, London: https://www.freud.org.uk/2019/09/18/the-uncanny/[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] Interview with Demetrio Paparoni, Domani, 17 January 2021

{{flexible[0].text}}

{{newsData.good_count}}

{{newsData.good_count}}

{{newsData.transfer_count}}

{{newsData.transfer_count}}

Short Loved, 2020, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 43x53 cm.

Short Loved, 2020, 琺瑯漆‧木板 Humbrol enamel on board, 43x53 cm.

分享

分享