In 1988, UNESCO launched a ten-year program, entitled “Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue.” This cross-national study viewed the Silk Road as the common heritage of East and West, which fostered cultural exchange in the Eurasian Continent. This program's definition of the Silk Road was primarily based on the concept of dieSeidenstrasse, an interlocking set of overland routes that connected the western Han dynasty and the Roman Empire, proposed by Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833-1905), a German geographer and founder of modern geography. In September 1868, von Richthofen arrived in Shanghai on a steamship, with the ambition to explore coal resources in inland China. In that quest, he traveled across the Gobi Desert seven times in four years. His map centered on Inner Asia, with China, the Mediterranean world, and even the Indian Subcontinent on the periphery of Eurasia. He understood the importance of the spice routes across the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, but for the Austro-Hungarian Empire, oceans were not a focal point of the imperialist competition for resources.

In 2007, Roderich Ptak published Die Maritime Seidenstrasse (The Maritime Silk Road ). He describes maritime navigation and trade in Asian seas prior to the sixteenth century and offers further insight into the indigenous peoples inhabiting the endless coastline and maritime worlds of the East China Sea, the South China Sea, the Sulu Sea, Java, the Strait of Malacca, the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, and even East Africa. During this time, trade between Asia and Europe was limited, but in the Age of Discovery, American silver extracted by Spanish colonizers was shipped to Asia (primarily China), and Asian products were sold all over the world as luxury goods. When the Europeans, who were more accustomed to navigating the Mediterranean Sea, arrived in Asian waters, they often needed to rely on the navigation skills and knowledge of local sailors. The monsoon was crucially important; in seas where the North Star was not visible, sailors navigated by identifying cloud forms and waves and observing the ocean surface and the behaviors of birds and animals near islands. Pre-modern rulers along the Maritime Silk Road had different conceptions of territory than sovereign states; sailors, merchants, and fishermen from different areas sailed and fished on the open seas, negotiating and trading with different groups.

With the advent of post-colonial deconstruction, the Maritime Silk Road in the twenty-first century became the focus of nation-building, politicization, and aestheticization efforts, such as China's New Maritime Silk Road project in 2013 and India's Project Mausam in 2014. Many Maritime Silk Road Museums and sites have been constructed. Conversely, the Maritime Silk Road could be envisioned as the interweaving of different worlds, which involve tributary systems, imperial trade, contemporary globalization, and different belief systems; Kunlun slaves, Persians, pirates, sailors, refugees, and boat people; Arabic, Sanskrit, Malay, and various pidgin languages; ports, islands, shipping, tropical climates, and plantations; spices, seafood, silk, porcelain, minerals, and opium… In this sense, the Maritime Silk Road has no center and no beginning.

Ptolemy's world map in the manuscript of Geography published in the 15th century. It represents the largest geographic range recognized by the Greco-Roman world in the classical times, and also reflects the communication between the Greco-Roman world and the Indian Ocean world.

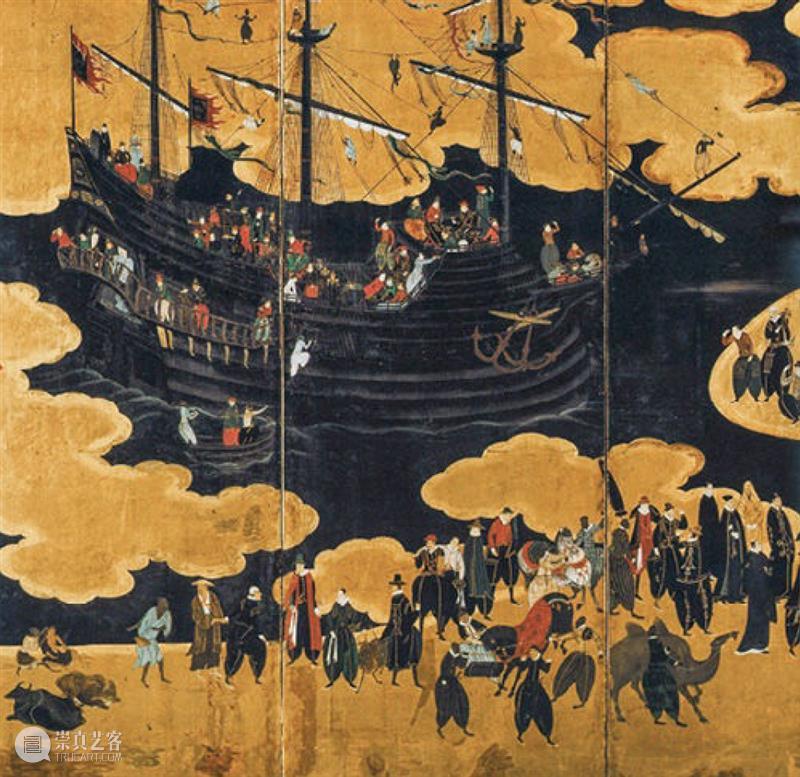

The "Nanban" merchants depicted on Japanese folding screens in the 16th century were Portuguese merchants who regularly came to the coastal areas of Japan to trade. The Japanese in the Azuchi-Momoyama period were keen to paint Nanban ships, various people and goods on folding screens.

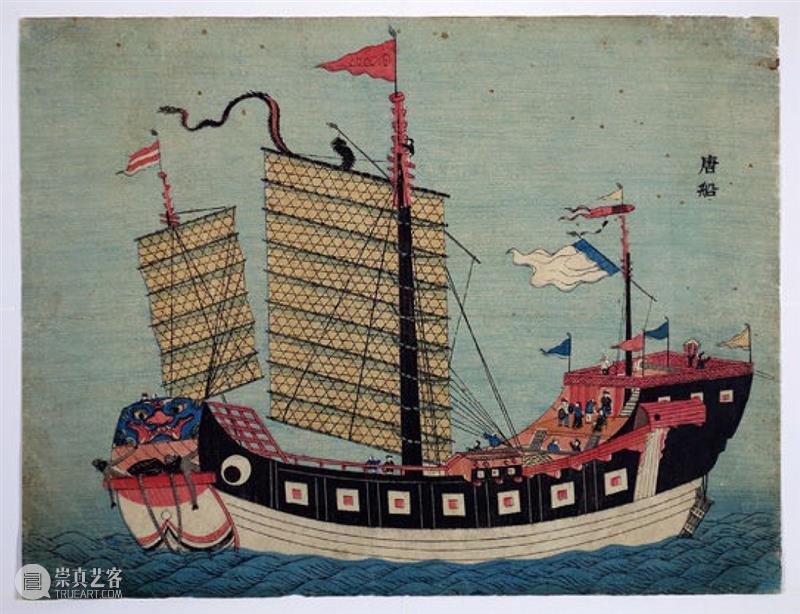

The "Tang Boat" depicted in a Nagasaki print is a Chinese merchant ship. China and Japan had maintained long-term trade relations, and Nagasaki was an important port where Chinese merchant ships call.

The above three pictures are adopted from Roderich Ptak, Die Maritime Seidenstrasse, Post Wave Publishing | China Friendship Publishing, 2019

On a basic level, the South sits on your right-hand side as you face a rising sun, or it is located on the lower part of the map, opposite to the North. In the context of colonialism, the South can symbolize the uncivilized wilderness, the tropics, primitiveness, nature, tradition, and backwardness. From its inception, this geographic concept with an embedded binary structure has inspired diverse visions of geography and networks of action. The term "Global South," which is related to the idea of the Third World, refers to south-south cooperation and solidarity among developing countries, as well as resistance to capitalist globalization. Due to the relatively free flows of capital and products and the relatively difficult flows of natural resources, technologies, and people, the South is easily consolidated under geo-political or post-colonial labels, or trapped by positionality of being the Other, the periphery, and the victim. Dependency theory, first proposed by Latin American scholars in the late 1960s, stresses that, because relatively backward periphery countries are dependent on advanced core countries, they are often exploited in international trade, which produces corruption and other ills.

Globalization has created counterpoints and spillover effects between the South and the North, creating the South in the geographic north, or the North in the geographic south. The northern centers of modernity in the current world system have experienced or are experiencing southernization. Examples include the southward migration of China's economic and trade centers since the Tang and Song dynasties, the capitalist industrialization that was built on the African slave trade and the plundering of natural resources in the Southern colonies, the southward transfer of China's excess capacity within the One Belt, One Road framework, and the tropicalization of several temperate northern countries due to climate change. Furthermore, the energy-intensive raw materials extraction and infrastructure construction related to developed countries' information industries often take place in less-developed regions in the South. In the context of the intensifying climate crisis, increased focus on the ecological fragility of the Global South has given rise to criticism of and resistance to extractivist. Extractivism is considered a short-sighted development model in which multi-national corporations make huge profits from the large-scale extraction of natural resources from a given area. However, these benefits are seldom shared with local communities and these practices further exacerbate the destruction of ecosystems and the displacement of indigenous people. These geographic visions and processes transcend historical cycles and national boundaries, becoming the foundation of today's epistemological plurality, which prompts us to ask, "What is the South? Whose South is it?"

Nikita Yingqian Cai is the Deputy Director and Chief Curator at Times Museum. She has curated such exhibitions as Times Heterotopia Trilogy (2011, 2014, 2017), Jiang Zhi: If This Is a Man(2012), Roman Ondák: Storyboard (2015), Big Tail Elephants: One Hour, No Room, Five Shows (2016), Pan Yuliang: A Journey to Silence (Villa Vassilieff in Paris and Guangdong Times Museum (2017), Omer Fast: The Invisible Hand (2018), Neither Black/Red/Yellow Nor Woman (Times Art Center Belin, 2019), and Zhou Tao: The Ridge in the Bronze Mirror (2019) and Candice Lin: Pigs and Poison (2021). She runs the Para-curatorial series and the research network of All the Way South, and is the co-editor of On Our Times and the podcast host of Rolling Congee. She was awarded the Asian Cultural Council Fellowship in 2019.

The Greater Bay Area Keywords Project is an ever-expanding think tank. We have collected 31 keywords from scholars around the world to launch the first round of thought processes. The project is continuously open to submissions worldwide, and we look forward to writers engaging in critical imaginations on culture, geopolitics, and technology around these questions, as mentioned above. Each keyword is illustrated in 300 words in English (500 words in Chinese). Please get in touch with us via email before you submit your manuscript. Once your manuscript is accepted, it will be published in English and Chinese on the Media Lab’s official website. Please find us at medialab@timesmuseum.org

推荐阅读

TACB展览:远方,大海在歌唱

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享