Recommendation

Between 1987 and 1992, she studied painting and stage design at the Fine Art College of Ulaanbaatar and Academy of Theatre and Fine Art of Belarus.

Her works of art cover a wide range of forms, from painting, sculpture, collage, to video. She has participated in many major international exhibitions, such as the Venice Biennale (collateral solo exhibition). Her works have also been exhibited in Chinese cities, including Shanghai, Hohhot, and Lhasa.

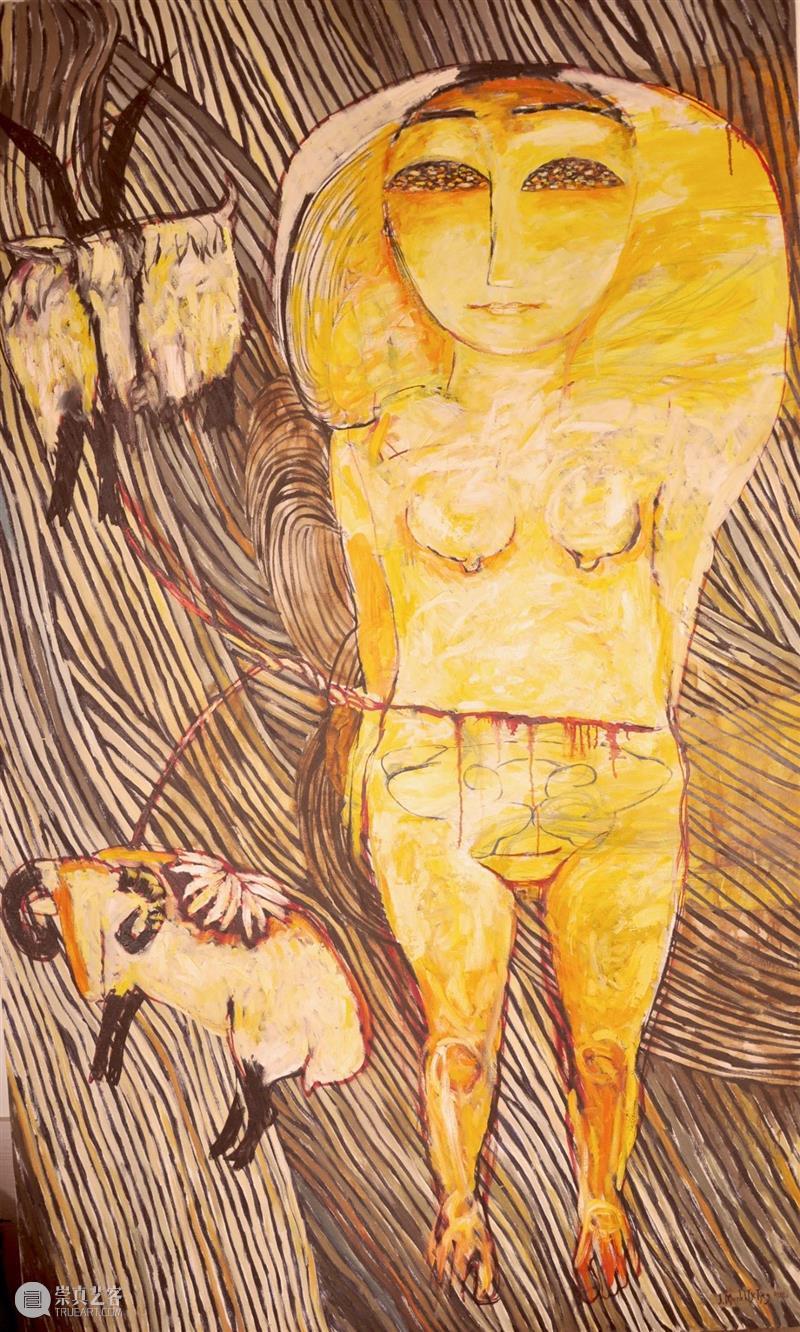

Her artistic creations have been influenced by the traditional Mongolian and Tibetan medical illustrations and modern spiritual therapy. From a unique female perspective, her works focus on ‘healing’ and ‘rebirth’, emphasising physical intuition and dreams. Using fragments of human and animal bodies, her paintings and sculptures visually narrate the process of collaging, stitching and assembling, aiming to heal the disordered social psychology and spiritual crisis. Her works attend to natural and social issues, always showcasing the importance of defending women’s rights.

Nomad Relays is very honoured to do an exclusive online interview with Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav and is grateful to her for allowing us to share it with you.

Chyanga (Qin Ga)

9 November 2021

Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav interview

Q

What led you to study art in the first place? Was there anything that left a deep impression on you during your study of art?

The beginning of my career as an artist seems to be a very slow process. In my work, the human figure plays an important role. When I was in art school, I first learned to draw a person's appearance truthfully in the tradition of realism, but it wasn’t enough for me.So, in order to create my own conception of the human, I embarked on new research. For example, I started to reassemble human organs such as the eyes, hair, and hands. It can be said that this became a bridge to my later work. An early encounter with Mongolian medical illustrations of human anatomy was really a crucial step for me. Illustrated books of ancient Tibetan medicine have had a great influence on me, too. These became the intellectual foundation that helped shape me as an artist.Inspired by the bodies depicted in medical books, I was able to give life into the human figures I have created in my work.

Q

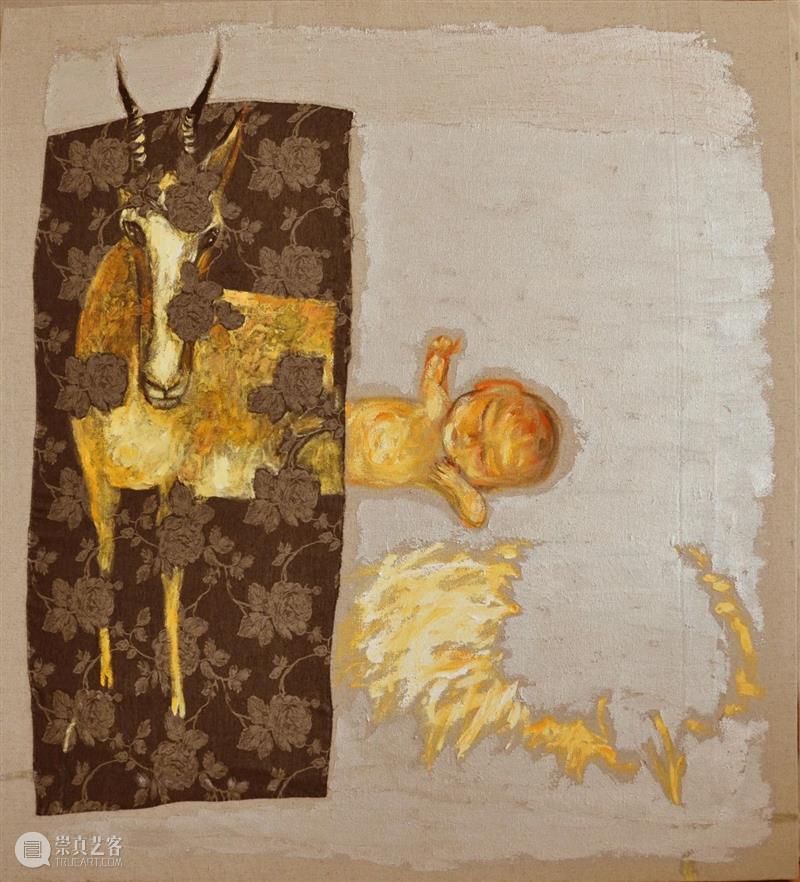

Your art works are grounded in Mongolian culture with its unique mode of thinking and in experiences of traditional life. ‘Dream of a Gazelle’ , for instance, is made of patches or different materials sewn into a whole piece. Please tell us the background of this piece of work and where you got your inspirations.

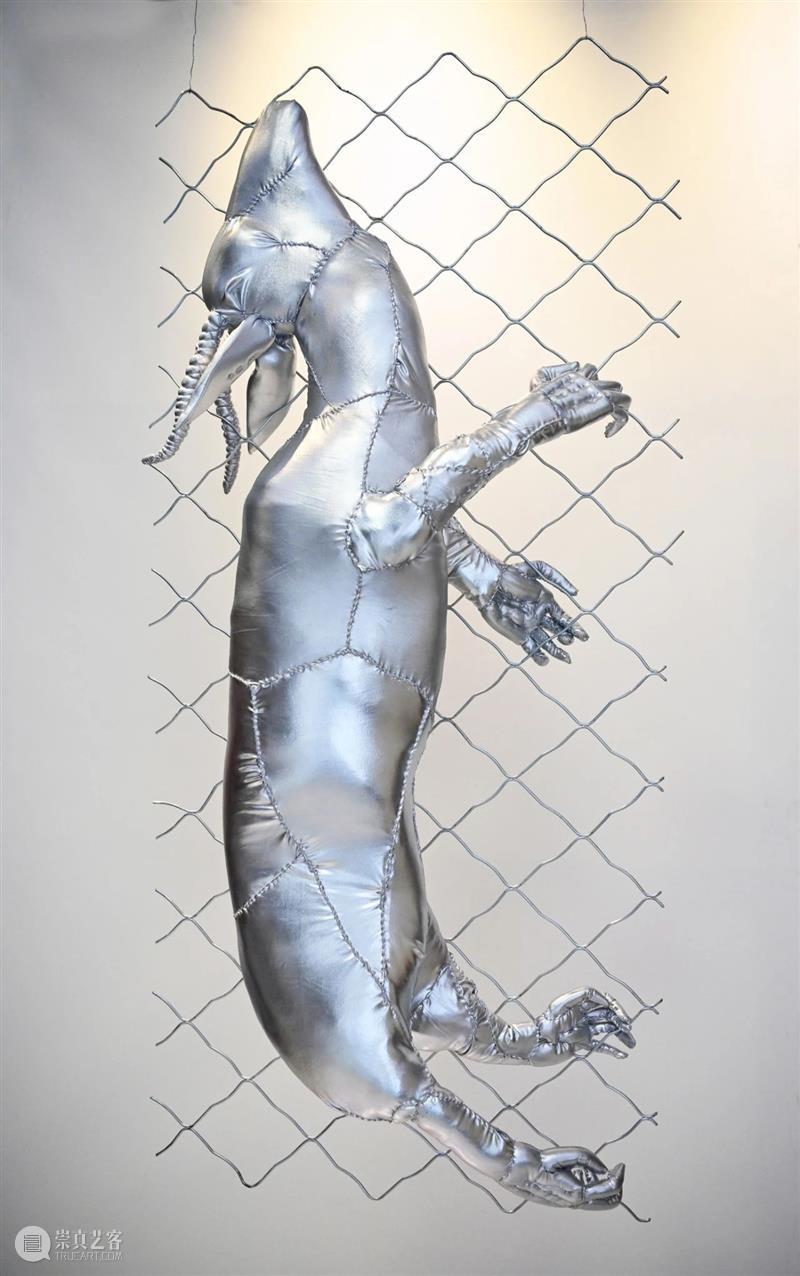

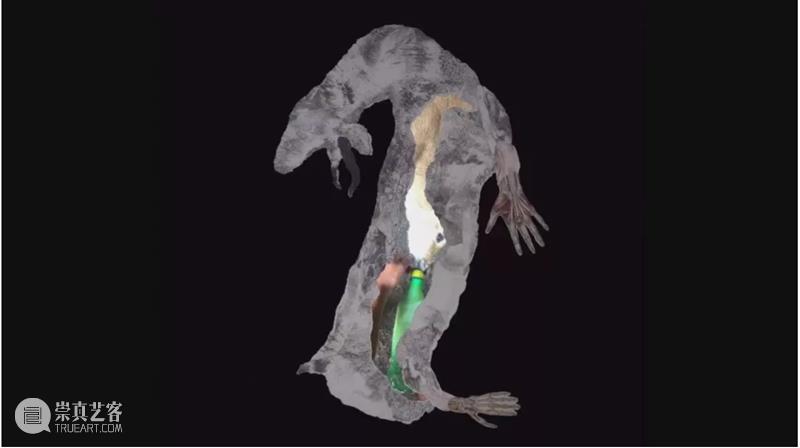

‘Dream of a Gazell’ is about tragic deaths of large numbers of gazelles on Mongolian grasslands trapped by hundreds of kilometres of iron fences built along railway lines. This is a fact that is not well known to the public, and it left me no choice but to address this issue and express my voice.In my previous works I have portrayed gazelles to convey ideas and conceptions about after life, caring, catharsis and healing, and human-nature connections. Gazelle is one of the key animals that constitutes the Mongolian ecological system and therefore it is an integral part of our nomadic life. The main narrative of this work is this: it portrays the metamorphosical transformation of a gazelle with its legs turning into human hands when it has no open space to go to.In other words, the fear of the gazelle has caused its transformation. By bringing the unknown deaths of hundreds of gazelles to people's attention through my artwork, my aim was to initiate a dialogue so that we pay more attention to this issue.

Dream of a Gazelle, 2021

mixed media,150x80x30cm

©Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav

Q

Let us explore your work from a linguistic perspective. The Mongolian word for patch/fragment is өөдөс. However, өөдөс does not just mean leftover pieces as it is usually understood. It is actually associated with the verb өөлөх, which means trimming and rearranging. The verb could thus also imply a critical attitude. Could I therefore ask whether your art creation has a sense of criticism embedded in it, if so, what is it?

Q

Leftover pieces or өөдөс has also a significant meaning in Buddhism. A monk’s clothes, for instance, are made with patches of cloth discarded by people, and wearing such garments is intended to show one’s renouncement of this world. To be sure, Mongolian reincarnated lamas tend to wear resplendent clothing and they also accumulate wealth. This could be justified as an act of absorbing the bad karma on behalf of the donors. We are just curious whether you have been exploring the Buddhist meaning of өөдөс and reflecting it in your art work. Forgive us if we are reading too much into your work.

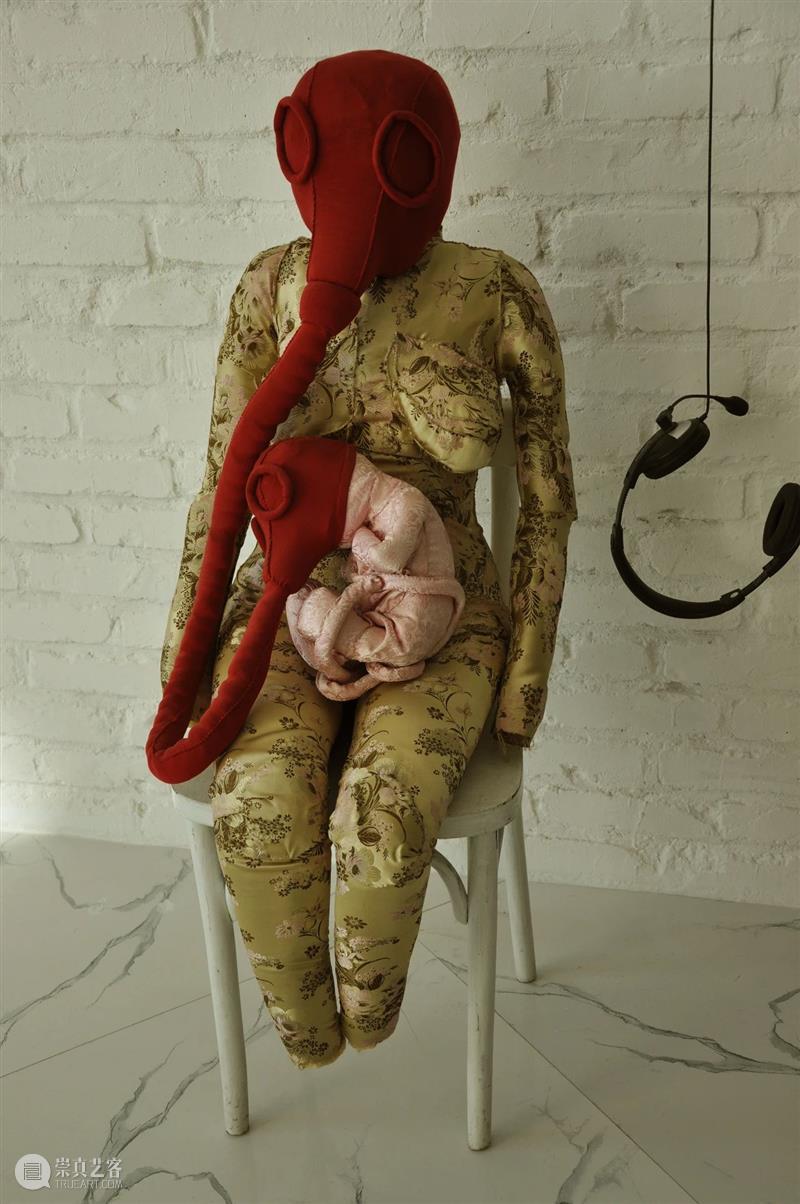

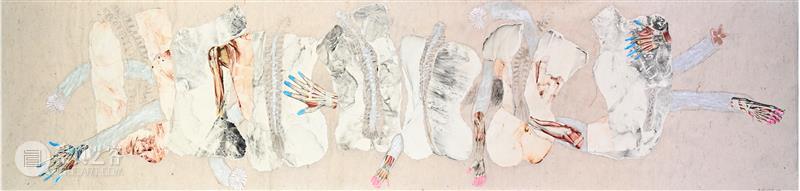

There is a fundamental concept in Buddhist philosophy that everything is interdependent. I have been trying to incorporate this idea into my work. In the cosmic sense, we are all fragments and pieces (өөдөс). Just as our bodies are comprised of numerous parts (өөдөс), so too is our mind made up of millions of pieces (өөдөс). The human body is a combination of many things, so I put together ripped pieces of paper and cut pieces of fabric to complete the idea of becoming whole. From this I got the idea of becoming whole and united. For me, the idea of becoming whole in my work is to imply the idea of healing. Humans have a natural intuition for becoming a whole and finding a balance. I believe that healing is a process by which many small parts come together to accomplish a unity.

Self Creation, 2011

stretch fabric, thread and needle, 80x40x35cm

©Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav

Q

You have depicted multi-faceted human bodies in your multi-media works. For example, we see human bodies in unsewn animal skins with exposed internal organs or skeletons. Bestiality of the human animal in your works is, if we understand you correctly, intended to challenge human or animal ontology. But what meanings or messages do you want to convey by showing internal organs and skeletons?

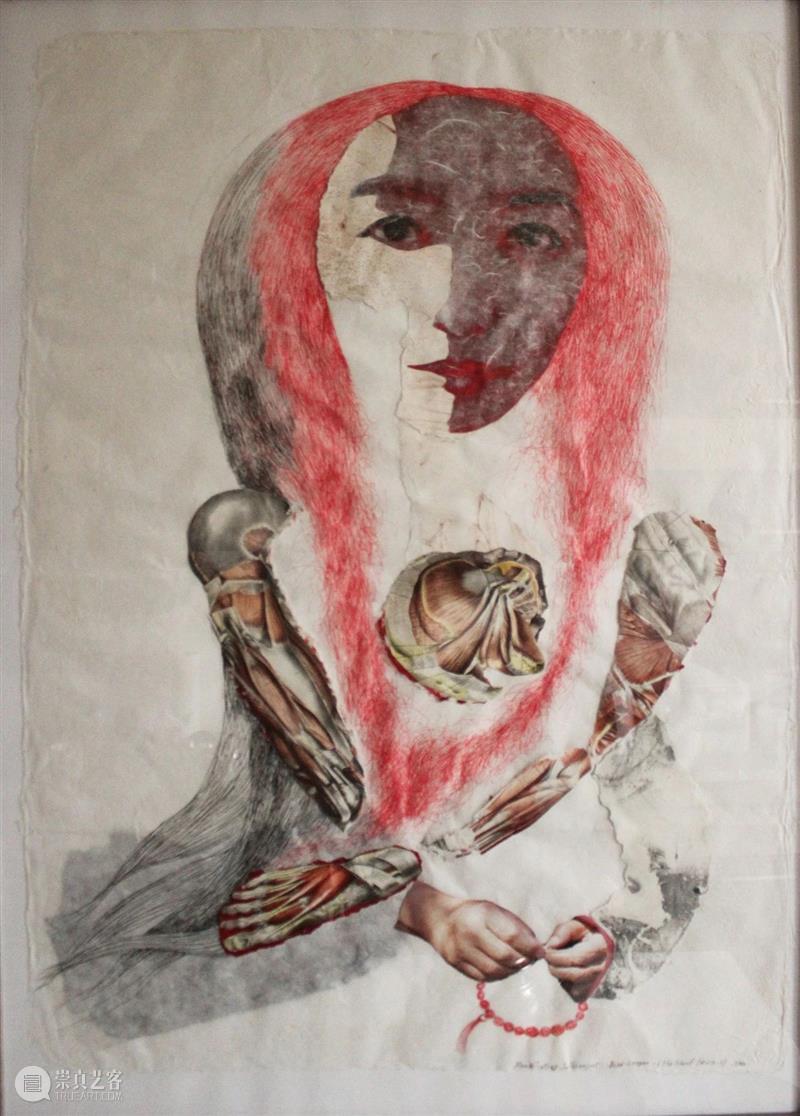

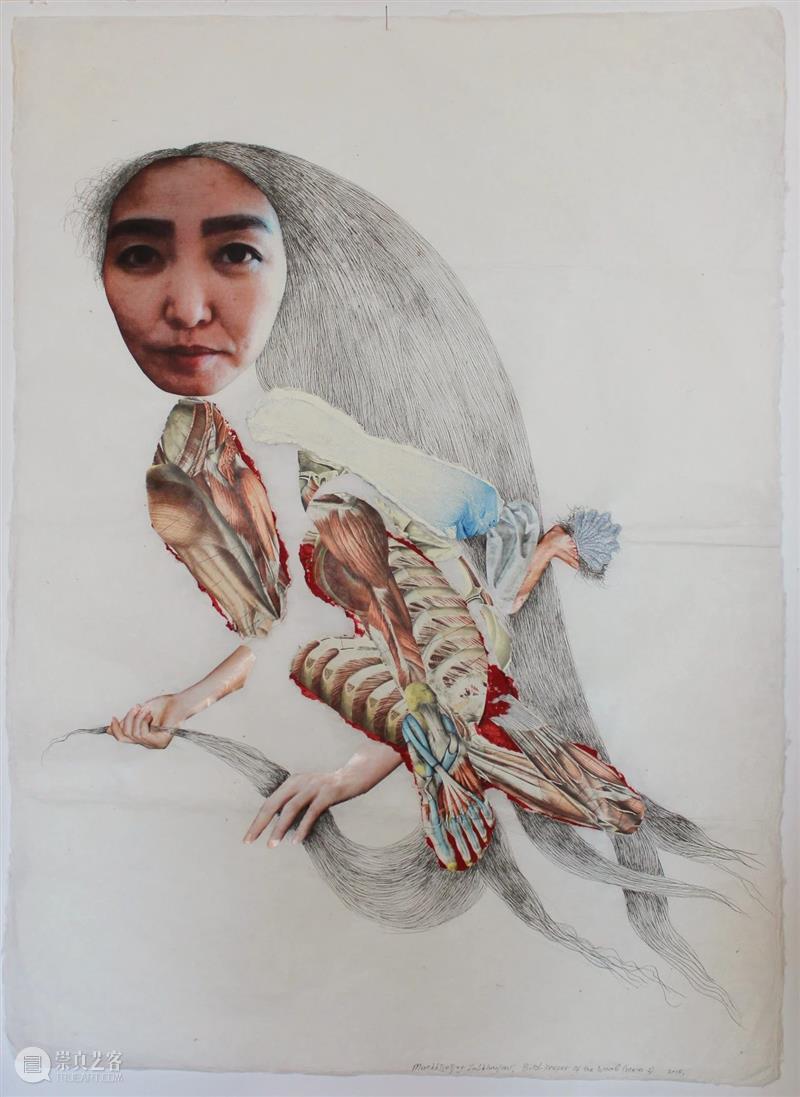

I aim to express the extraordinary power of the inner world through the internal organs, skeleton, blood vessels, and heart. On the other hand, by revealing all the inner organs of a body, I want to show how fragile it can be. For example, let's talk about the umbilical cord in my work: a human body organ. The umbilical cord exists temporarily in a woman's body. In my work, I use it to symbolise the connection between the human world and the spiritual world. And this also shows the inner power of the human body. It can be seen as the link between the body and the soul of a person who is about to be born in the mother's womb. In my work, I show the details of the fusion of people with animals. This suggests that humans symbolise their intuition through animals.In the world of intuition, humans and animals are alike. The depiction of the fusion of animals and humans as though they were mixed and blended into each other is intended to imply that animals are a substitute for human instinct. The power of animals is great. When a person loses their balance, they try to regain it with the energy of animals. It means that a person is syncing with animal instinct. For example, my work ‘The Bird Keeper of the Womb’ is about a character I created with the idea that a mother has the natural power/ability to transform her body to protect her child.It is an image that combines the characteristics of a crow with those of a woman's hair.

The Bird Keeper, 2013

bronze with silver patina, 40x40x30cm

©Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav

Q

Skeleton is a very important element in Buddhist art. Have you in any way been inspired by Buddhist art?

In Buddhist medical practice, medicine falls into the real world, and healing falls into the spiritual world. I have turned the idea of spiritual healing into a concept in my art practice. So, basically the traditional folk medicine has become the conceptual bedrock of my work. Therefore, the ideas and images in traditional spiritual healing are reflected in my work both directly and indirectly. The depiction of how spiritual healing comforts the organs in my work is an intellectual expression of healing the mind. Buddhist art has taught me how to turn powerful ideas, abstract things, metaphors, and symbolism into the visual language, in a way that exemplifies for me to become free-spirited as an artist.

Born From Flower, 2012

mixed media on sa paper,80x55cm

©Munkhtsetseg Jalkhaajav

Q

You seem to have a special interest in depicting human hands. What do hands signify in your works? Do they have any metaphoric meanings?

In my work, human hand shows up quite a lot and plays a key role. This is derived from the performing arts which I once studied.In the language of performing arts, the hand represents the human body. Hand gestures, movements, and expressions represent a major part of the meanings expressed in my work. On the other hand, in traditional folk medicine a hand is used to diagnose the human body by feeling the pulse. In this sense, a hand symbolises a pulse in my work. So, the hand is like a mirror of the human body. Also, although the hand represents creativity, one can also say that what has been created may pose a threat to animals indirectly, depending on what impact it brings on them.

Q

Many of your art pieces are about dreams. What is your perspective on the relationship between dream and reality?

Dreams are abstract in many ways, but the plot and events in the dream can be narrated as a story. And that narrative is what makes it real for us. It is through this reality that a person retains and communicates dreams. In my work, abstract ideas are made concrete and real in a process just like a dream is narrated. This is very much like the [Mongolian] saying that ‘The truth of a tale is in the intuition.’

So, I personally think that dreams are the reality in the abstract world.Bardo Thodol, or, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, gives an interesting spatial description of dreams in terms of the realm of the in-between world.

‘The foetus in the mother's womb; the dreamer who is asleep; the meditator who is detached from the surroundings’: these are the environments in the realm of the in-between world.It is fascinating to think about how this world coexists with this airy world that we breathe in, and how such a delicate connection has been created.We perceive what is happening in dreams as real.Making it into an artwork seems to be relevant to people's daily lives.

Q

In your art world, it seems that males exercise violence by alibi as though they have an unforgivable original sin, whereas females are brave guardians of humanity. Once again, please forgive us if we get it wrong. But what do you think is the place of women’s identity in art, or what is the role of feminism in your art creation?

I think that the mental and intellectual strength of women to overcome problems of nature and society is very unique, even in the field of art .I believe that women's natural power, as well as the strength acquired from life experiences, can turn anything into healing and protection.Based on this idea, I have tried to show in my work that as long as a woman becomes conscious of her natural power, she can heal all the injuries and mental illness caused by sufferings in the past.In my opinion, feminism is about attempts at restoring the lost equal rights in a society. I think it's an effort to find strength for self-defence. So, I think my work relates to feminism in terms of defence of rights, or women’s participation in issues concerning nature or society in order to protect their rights.

Q

You have attended many international exhibitions and art events. How to get one’s work, which is often culturally embedded, recognized internationally must be quite a challenge. We would like to hear your reflection on the center-periphery relationship in the discursive power structure of culture.

Cultural differences among countries are huge, but today, I think those differences are disappearing as those cultures merge with each other. The Westerners used to and still think they are the centre of the world, but this centre has now pluralised and it can be anywhere and in any number. The Westerners tend to think in a realistic and logical way. Probably they insist on that way. However, whether in Western traditions or in Asia, no matter where it is, there have always been various types of abstractions, strange metaphors, and symbols. No matter where we come from, we are connected on this narrative and visual language.

Q

Today’s art world tends to be over commercialized because of the impact of capital. We often say that it is difficult to judge an artwork by money, but in reality, the worth of our art is often judged in terms of how much money it can fetch. What is your thought on the relationship between art and business?

Any art is created for a purpose. From the earliest times of human art to the present day, it has been created for a purpose. The commercial art also has a purpose. Whatever the purpose, the value of an artwork lies in what idea it contains. Only time and destiny will test it.

Q

Accelerated urbanization is a common phenomenon in ‘post-development’ countries, and Mongolia is no exception. What is the state of ‘nomadic culture’ in Mongolia today, or what is the place of nomadic culture for a rapidly urbanizing country like Mongolia, whose nomadic heritage is the marker of its national identity? We are particularly interested in your thoughts on the contemporaneity nomadic spirit, and how artists can make more contribution to promoting it.

The Mongolian traditional nomadic culture is a unique way of life.But it had been damaged so much during the 70 years of socialism. It was almost destroyed.People have been cut off from their own culture. Mongolia’s current situation of nomadic culture is an effort to revive the past.On the other hand, like other countries, it has a dream to develop in a modern way.

It seems to me that we are going in two [opposite] directions of development, and we are in a state of chaos while trying to reconcile them.In such a messy situation, Mongolian artists are trying to find their own voices.There is also a tendency to recover their own identity and carry on from there.But it is precisely this chaotic situation in Mongolia that in a way feeds artists with interesting data, facts, and meanings.Just like bad things don't always go bad, I think that some problems come with their own solutions.At a time when the social psych is so damaged and out of balance, I believe art can heal and restore it.

Interviewer: Chyanga(Qin Ga),Uradyn E.Bulag

Video and editing: Jantsankhorol Erdenebayar

Translation: Gunsen Khurelchuluun

English Editor:Uradyn E.Bulag

Type setting:Yundan

The copyright of the material on this site (including without limitation the text, artwork, photographs, images, music, audio material, video material and audio-visual material) is owned by NomadRelays. You may request permission to use the copyright materials on this site by email to nomadrelays@hotmail.com

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享