采访、编辑 | 杨紫

Interviewed and Edited by Yang Zi

“一切都是有意识形态的,包括品味本身。这是我想要表达的。”

我刚开始做收藏的时候主要收藏的是新水墨。2004年左右,收王冬龄,还有川美的一些不使用水墨媒介,但有很好水墨基础的艺术家。原因是存在一个政治正确的问题,但这个政治正确也不是因为我是中国人。对于当时十七、八岁的我,艺术品单件作品都算不上便宜。一、两万美元到后来的十几万或者更高的价格,都不算便宜。它本质上是一种投资,回到投资的角度,我作为一个投资人,就会产生一个道德问题:凭什么你可以按照自己的喜好和能力做好一笔投资?所以我并不觉得油画或西方特别当代的艺术品对我而言有任何的驻足点。因为我流的不是那样的血液。说白了,我不是在古堡里长大的。所以对于西方当代艺术家正在讨论的话题,我可能最多是一名前排的观众,不觉得自己能上台。西方收藏家、策展人和艺术家共同组成了那整个事件和整个环境。所以我对新水墨就更感兴趣,因为家里的长辈从小就接触水墨,我小时候就有很多家人的朋友也是在收藏水墨。所以我对于这些艺术家本身更能有体会,这种体会其实是对人的体会。新水墨的问题是没那么多好的艺术家。70年代之后就没有出过还有水墨文化根基的人——我觉得咱们这代人就是在很纯粹的资本主义环境里长大的。

回到“品味”这个话题,我觉得品味原本是一件很私人的事,最开始听到“品味”这个词,就觉得它特别高级。大概2002、2003年,我初中的时候,我妈书架上有一本书,她看了以后会和我聊书里的内容,是英国作家彼得·梅尔(Peter Mayle)写的《关于品味》,非常小资的一本书,主要讲法餐、衣服还有一些生活方式。我最近在抖音上看到有人提起这本书,比如说萨维尔的裁缝、米其林等等。我爸就非常鄙视那本书,他认为这些不是正经事。正经事应该是志向之类的。他把品味当作一种衍生品。我父亲对于品味本身还是有追求的,但他把品味当成品格或品德以外的衍生品,品味自己不是独立存在的。他的想法很传统,很中国人。

看完这本书之后我就比较能理解我妈。因为她出生在一个知识分子家庭,她爷爷是她浙江老家中学的校长,那所学校变成中学之前是一个私塾。她小时候,我外婆去上海出差,别人都往回带一些电饭锅这些东西,但我外婆带回来的是蕾丝边桌布,但我外公就觉得不是非常理解。那时候都流行看东欧和俄罗斯文学,但我妈是看西欧文学偏多,像简·奥斯汀。那时候我就觉得品味是非常女性向的,这是我最开始对品味的理解。有一部皮尔斯·布鲁斯南主演的《007》里说过这样的台词,特别性别主义:“男人最需要的就是责任心、勇敢和一些坏品味。”那时候我才意识到,哦,男性也可以有品位。后来,品味成为了我长时期在追求的东西,满足了我特别强烈的身份认同需要。一件事情如果你的做法和别人不一样的地方才是你自己,最不一样的那1%才是自己的缩影。

无题——人、海景与猫 |

Untitled - Person, Seascape and Cat

我成长在一个非常传统的中国家庭,母亲有自己的东西想偷偷跟我分享,父亲是一个半缺失但有严格框架的角色。我现在回想,我从小就对工业设计比较感兴趣,当时家里最有工业设计的东西基本上是我妈的化妆品的瓶子,我如果拿着看,父亲就会很生气。于我而言,品味一开始就是一个很标签化的、很女性向的东西。从那部《007》开始,虽然那段台词现在看起来很油腻,但从那时起我意识到,男性也可以有。

接着视野里就出现了一位关键人物:丘吉尔。他长得谈不上英俊,尤其是老年的丘吉尔,生活作风又很不严肃,作为一个政治人物甚至是一位战争英雄,他本质上还是挺纳粹的,包括一些对华政策,但是这个人又受到很多人的追捧,他对雪茄、威士忌又非常精通,甚至他的喜好成为了很多精致的人的追逐对象。

有一支以丘吉尔命名的雪茄,最近因为疫情的原因暂时停产了,价钱现在翻了十倍,因为伦敦人把它买光了。当时我就在想为什么有人会觉得丘吉尔品味,在我眼里他就像是我爸类型的人。我爸怎么可能品味好呢?所以后来我发现品味好像不是完全独立的,我爸说得好像也对,品味好像不是独立存在的,甚至和品德、品格败坏都有关系。

丘吉尔这件事让我觉得品味这件事不值得专门研究。我认真买过画,但后来我就不喜欢买画了,手里留着的画也越来越少。我2017年买了两位艺术家的画,那时候还挺便宜,后来涨得特别多,尤其是今年,大概涨了十倍。当时我买画的原因是一位认识的代理人和那位艺术家关系很好,他也很少给我强推作品,所以我就买了。后来价格疯涨,他又问我要不要卖掉,因为他有其他的客人向他询价,所以我就又把那幅画委托他帮我卖掉了。但是从始至终,我是比较讨厌那幅画的。我觉得那幅画做作,特别追求品位,而且追求的是坏品味。就像是90年代纽约的风格。他使用艳色,但又不是发自内心的。不是他心里想用荧光黄,而是他觉得荧光黄这个颜料值得投资。

后来我就发现品味是很政治正确的,它并不是像我小时候想象中的那样那么个人化。它是不能讨论道德败坏的,当它与道德败坏相关的时候,它连被称为品味的价值都失去了。比如说,现在有几个男同志在一起聊天,特别大声地对男性的喜好评头论足,这时候旁边的人可能会觉得有点烦,这种烦和听到几个男性在特别油腻地讨论女人是一样的。但如果这件事发生在60年代的密西西比或德克萨斯,这就不是品味问题了,他们甚至会被抓起来。但现在来看,它就是一个品味问题。

我一直认为艺术与道德是强相关的,基本上中国书法家的道德与他作品的留世和传颂是有很大关系的,但西方并不是这样。道德和艺术的强相关的看法我从没和别人聊起过,觉得是不是太迂腐了。其实我也没觉得迂腐是件坏事,但感觉一旦你谈道德,大家就会觉得你太正经、太严肃了,甚至这种严肃程度要超过谈硬科技,现代人不想贴上任何迂腐的标签,但道德一旦和实践挂钩就显然是一件太迂腐的事,所以我就一直偷偷在心里关注艺术家的道德和他作品之间的关系。

忻慧妍 Winnie Yan Wai-yin

局部失明 | Localized Blindness

2019

单频录像,彩色及黑白,有声 |

single-channel video,

colour & B&W, sound

19’45”

我昨天还仔细思考过这个问题,我现在不喜欢什么?不喜欢哪个类型的艺术家?我觉得是那些不敢探讨道德,但他们的作品中却无时无刻不在表达自身立场的一类人,他们的行为和他们塑造出的环境是相违背的。这就不太自主了,或者说,不太自由。

自由对我来说,是主观和客观上能不能承受和逃离。如果一直拥有这两个选项或能力,那么我就是自由的。不能承受就不承受了,这就叫逃离。但还有一种情况是,你既无法逃离,也不能承受,我觉得这就是不自由。承受不了但能够逃离,或逃离不了但能承受,我觉得这还算自由。

从财务上来说,我是一个生意人,是一个投资者。我要承担市场的波动。如果单纯从财务的角度出发,我是极不自由的。比如说人对人的方面,从投资角度来说是机构对机构,比如说我是做地产的,对方是做二级市场的,那我们可以比比谁现在资产更自由,谁的流通性更好。人和人之间如果探讨自由,那么肯定是讨论财务以外的问题。

比如我的负债率可能是相对较高的,我的可支配财富总量可能高过一部分人,但高过的这部分人,我们的负债率可能又是一样的。我只是基数比较大,所以我的可支配部分的绝对值比较大,但是可能我的负债率要更高。当市场出现较大波动时,我要承担的会更多。所以我觉得关于自由的问题好像就只能探讨财务或资本以外的部分。我觉得我的不可逃避和承担不了,很多时候都是心理上的。

我原来主要在和一些国内国外的资金方、资本或者说机构一起房地产和相关的资产,但忽然间就不能做了。对我而言就存在由浅到深的诸多挑战,我十年的从业经验就没有用了,本身积攒的工作上的社会关系也就没有用了,打磨出的工作方式和方法论也没有用了。就像是一位语言学家,一夜醒来,他研究的这门语言就不存在了,或者都是错误的。这首先就会让我产生一种巨大的自我怀疑。这个时候,如何跟自己相处就是一个很大的问题。

更具体的是,我需要遣散我整个团队。团队里我招进来的有五个人,此前他们都是自己领域里的佼佼者。我偏向于有明确的工作方式,大家用自己的工作方式互相磨合,所以我们招的人都不是那种之前在很有性格的投资机构工作的人,而是专业人士,比如律师、会计师或咨询师,没有之前企业的很强的烙印,又很想转行做投资的人。我习惯就工作方式和同事展开激烈讨论,但不习惯对投资风格和品味的问题展开讨论。投资是一个很讲品味的事。

换句话说,我的公司里,投资的方向都是我的方向。我统一了方向,大家再去讨论谁的方法更好。这个团队在一起的六年,可能一年里只有三个月在看项目,有三个季度的时间都在研究方法。但突然之间好像就什么都没了,需要遣散大家——之前有半年的时间是明知不行了但还在坚持的状态。

他们进公司的时候都30多岁了,陪着一个20多岁的小孩儿干了小十年,在快40岁本该定下来,找到自己在行业中位置的时候,他们的行业消失了。我那时候在工作上还有点傲慢,对自己工作方向都很笃定,但后来客观上又阶段性地证实了它是正确的,这就有养料去滋养了那种傲慢。

决定方向是很个人化的,我没有办法在团队里做到民主、公正、自由,因为它们在小范围的团队里将消耗大量的成本。我运营的不是一个体系,只是一个运输工具,这辆车怎么跑得更快,跑得更准,需要用很强权的方式。现在看来,这种事和我的性格是很违背的。我不是一个很享受强权的人,但我的企图心和虚荣心又很强,就导致我选用了一种自己不习惯、自己看来不道德的方式,去成就自己的企图心和虚荣心。后来一衰落,退潮了,浮出水面就是这些礁石,需要在礁石上行走的只剩下我自己了。这就是既无法逃离也无法承受的不自由。

一个人的过往是他最不能逃离的,这些事确实是你自己为之,你自己又没办法理解那时候的你为什么这样做,所以你就又没法承受。自己的过往不单单不能逃离,人们还会倾向于把自己的过往变成一种特别笃实的、不能变化的东西,变成一种道德体现。我们想的事可能和道德有关系,但我们做事时,事情的发展往往不受道德的逻辑支配。

Everything is ideological, including taste itself. That is what I want to express.

When I first began collecting, I was mainly collecting new ink art. Around 2004, I was collecting Wang Dongling, alongside some other artists from the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, who were not working in ink but had a strong foundation in the medium. This choice had something to do with political correctness, but this political correctness was not because I am Chinese. For someone like me, then in my late teens, a single artwork was not cheap. They went from ten to twenty thousand yuan up to several hundred thousand or more, which was not cheap. It was in essence an investment, and getting back to this investment perspective, as an investor, a moral question arises: what makes you think you can make a good investment based on our own preferences and abilities? For that reason, I never found oil paintings or very contemporary Western artworks compelling. It just wasn't in my blood. Simply put, I didn't grow up in a castle. When it came to the issues being discussed by Western contemporary artists, I was at most a listener sitting in the front row. I didn’t think of myself as someone who could take the stage. Western collectors, curators and artists together comprised the entire affair and atmosphere. I was more interested in new ink art. Everyone in my family had been steeped in ink art from a young age, and many family friends were collecting ink art. This gave me a better feel for these artists, a feel for them as individuals. The problem with new ink art is that there aren't that many good artists. After the 1970s, no one else has come up with deep roots in ink culture—I think our generation came of age in a rather pure capitalist environment.

Back to the question of “taste,” I think it is a very private thing. When I first heard the word, I thought it sounded classy. In about 2002 or 2003, while I was in middle school, there was a book on my mother's shelf, which she would tell me about after reading. It was Acquired Tastes, by British writer Peter Mayle. It was a very bourgeois book about things like French cuisine, clothing, and lifestyles. I've seen people mentioning this book on TikTok recently, talking about Savile Row tailors and Michelin restaurants. My father disdained this book, finding these pursuits frivolous. What really mattered to him was aspiration and ambition. He treated taste as a derivative. My father did pursue tastes of his own, but he saw taste as a derivative product, outside of personal character or moral fiber, not something with its own independent existence. His thinking was very traditional, very Chinese.

After reading this book, I was better able to understand my mother. She was born to an intellectual family. Her grandfather was the headmaster of the middle school in her hometown, which had been a traditional private academy before that. When she was young, her grandmother went on a business trip to Shanghai. The others came back with rice cookers and the like, but she came back with a lace tablecloth. My grandfather wasn't very understanding about that. In those days, literature from Eastern Europe and Russia was popular, but my mother preferred Western writers such as Jane Austen. At the time, I thought of taste as a very feminine thing. This was my earliest understanding of taste. In one of the James Bond movies, Pierce Brosnan has this really sexist line: “What a man needs most are responsibility, courage, and bad tastes.” That was when I realized that men could have taste too. Later, taste became a longstanding pursuit of mine, something to satisfy my powerful need for identity affirmation. If there’s something you do different from others, that is what makes you you. That 1% that is different is the real microcosm of you.

I grew up in a very traditional Chinese family. My mother had things of her own that she wanted to share with me on the sly, while my father was somewhat absent, but also had a very strict framework. Thinking back now, I was interested in industrial design from a young age. At the time, the closest things to industrial design in the house were my mother's makeup bottles. My father would get mad when I played with them. For me at first, taste was a very stereotyping, very feminine thing. Though that line from James Bond may sound slimy today, it led me to the realization that it could be masculine as well.

Then a key figure soon appeared in my field of vision: Winston Churchill. He's not exactly dashing, and especially in his later years, he was not a very buttoned-down person, but as a political figure, he was a real war hero. He was actually a bit of a Nazi, including in terms of his policies towards China, but he is revered by many people. He was also very well-versed in cigars and whisky, and his habits became a model for many to emulate.

There's a cigar named after him, and when production was halted by the pandemic, prices exploded, because Londoners bought up all the supply. I was wondering why people thought of Churchill as someone with taste. In my mind, he was someone like my father. How could my father have good taste? That is why I eventually realized that good taste is not entirely independent. I think my father was right in a way. It seems taste is not independent, and may be connected to character, moral fiber, or lack thereof.

The case of Churchill got me thinking that taste is not worthy of dedicated research. I was serious about buying paintings in the past, but after a while, I didn't enjoy buying paintings anymore, and am holding on to fewer and fewer paintings. I bought works by two artists in 2017. They were quite cheap then, but then the price rose a lot, especially this year, roughly ten times the original price. I bought them because a dealer I knew was close with the artist. The dealer rarely gave me such a strong recommendation, so I bought it. Then, when the price was rising like crazy, he asked me if I wanted to sell it, because he had other clients asking about it, so had him sell it for me. I hated that painting the whole time. I thought it was very pretentious, very intent on pursuing a particular taste: bad taste. It was like the New York style of the late 1990s. He used bright colors, but they weren't from the heart. He didn't want to use fluorescent yellow from the bottom of his heart; he just thought this paint was a worthy investment.

I later discovered that taste is very politically correct; it is not as individual as I had originally imagined. It cannot discuss moral depravity. As soon as it gets involved in moral depravity, its value as something called taste is lost. For example, if several homosexual men get together and debate the habits of men in a loud manner, they may annoy the people around them, but that annoyance would be the same as if they were loudly and lewdly talking about women. But if this were to take place in 1960s Mississippi or Texas, it would no longer be a question of taste. They might even be arrested. Today, however, it is a question of taste.

I have always felt that art is strongly connected to morals. The moral character of Chinese calligraphers is closely connected to how well their works have survived and been praised through the generations, but this is not the case in the West. I've never discussed my views on the strong connection between morals and art before. It feels too pedantic. I actually don't think being pedantic is a bad thing, but as soon as you discuss morals, people think you're too serious, rigid like hard science. No one wants to be labeled pedantic, but linking morality to practice is apparently too pedantic, so I have always just secretly watched the connections between artists’ morality and their artworks.

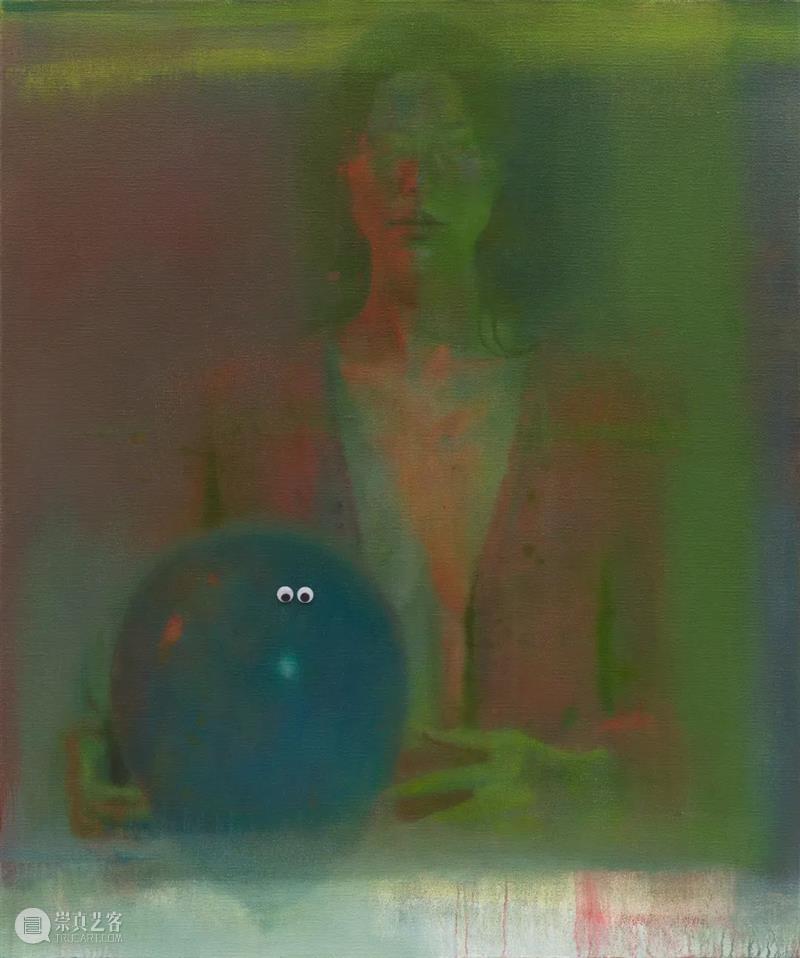

谢其 Xie Qi

夺目之看 | The Glorious Glance

2020

布面油画 | oil on canvas

120 × 100 cm

I was thinking yesterday about what things I don't like these days, what kinds of artists. I think it’s those artists who don’t like to talk about morality, but are still always expressing their viewpoints in their works. Their actions are antithetical to the environment they are creating. This is not very proactive, or to put it in other words, not very free.

Freedom is about whether you can objectively and subjectively endure and escape. If you always have those two choices, then you are free. If you can't endure, then you don't endure. That is called escape. But there can be a situation where you cannot escape, but you cannot endure either. This is not freedom. If you cannot endure, but you can escape, or you cannot escape but you can endure, I think that counts as freedom.

Financially speaking, I am a businessman, an investor. I must endure the turbulence in the market. From a purely financial perspective, I am not free. In comparing between one person and other, or from the investing perspective, between one organization or another—let's say I’m in real estate, and the other person is in the secondary market—we can talk about whose assets are freer, and who has better liquidity. But when people talk about freedom between one another, they're certainly talking about things other than finances.

For example, my debt levels are relatively high, and I may have access to more wealth than some people, but we may have a comparable level of debt. I just have higher base numbers, so the absolute value of the disposable portion is relatively large, but my debt level may be higher. When there is turbulence in the markets, it hits me harder. That is why I feel that any discussion of freedom should talk about those things outside of wealth or capital. I think that a lot of my inability to escape or endure is often psychological.

I was previously working together with different Chinese and international investment groups on real estate and related property, but then suddenly I couldn’t do it anymore. I was faced with many challenges of increasing depth. My decade of industry experience became useless, as did the social relationships I had cultivated, and the working methods and methodologies I had honed. It was as if a linguist woke up one morning to find that the language he researched had ceased to exist, or was completely wrong. At first, this caused a great deal of self-doubt. It was hard to figure out how to just get along with myself.

蔡坚 Cai Jian

Hyperfocus

2021

布面丙烯 | acrylic on canvas

Φ200 cm

On a more concrete level, I had to dissolve my entire team. There were five people I had hired personally, all of them already outstanding in their own respective fields. I prefer a clear working method, where everyone comes together using their own approach, so we don't tend to hire people who have worked at investment firms with very distinct personalities. Instead, we hire professionals, such as lawyers, accountants, and consultants who do not have a strong imprint from their previous company, and would really like to shift into the field of investing. I’m used to engaging in heated debates with my coworkers about working methods, but not about questions of investment style or taste. Investment has a lot to do with taste.

In other words, the investment direction of my company is my direction. I set the direction, and everyone discusses who has the best approach. In the six years the team was together, we would spend three months of the year looking at projects, and three quarters discussing research methods. But suddenly it seemed there was nothing, and we had to dissolve the team. There was half a year before this when it was already clear things were bad, but we continued to hang on.

They were in their thirties when they joined the company, and spent the better part of a decade working for a kid in his twenties. Now, at forty, they should be finding their place in their industry, but their industry has vanished. I was a bit arrogant about work back then, and was very confident about the direction of my work, but it was objectively shown to be correct over time, and that fed into this arrogance.

Choosing a direction is a very personal thing. I could never make the team democratic, just, and free, because that costs too much in a small team like that. I wasn't operating a system, but a vehicle. It required very concentrated control to operate it with speed and accuracy. Looking now, this is quite unlike me. I’m not someone who enjoys power, but I am also ambitious and vain, which is what led me to choose an approach that I find strange and immoral. Then, the decline. The tide receded, revealing these rocks. I’m left to walk on these rocks alone. This is that lack of freedom of being unable to either escape or endure.

One's own past is the most impossible thing to escape. These are things you actually did, but you cannot understand why you did them at the time, so you cannot endure them. Not only is the past inescapable, people tend to treat their past as a solid, immutable thing, an embodiment of morality. Our thoughts may be connected to morality, but when we do things, these things may not always develop according to moral logic.

本次展览将持续至2022年8月7日。

The exhibition will continue through August 7, 2022.

相关链接

“贮藏(2022)”展览项目系列推送「艺术家」之(五)魏晓光

“贮藏(2022)”展览项目系列推送「艺术家」之(四)赵要

“贮藏(2022)”展览项目系列推送「艺术家」之(一)何迟

“贮藏(2022)”展览项目系列推送「文章」| 杨紫:贮藏,以及枝形挂灯的案例

“贮藏(2022)”系列推送「文章」| 杨紫对谈王光乐:“路过缓慢的货架”

【展讯】麦勒画廊恢复开馆 | 当前展览“贮藏(2022)”已对外开放

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享