Watermelons, Mushrooms, Tents: A Giant Boy’s Resting Places

Lu Mingjun (Curator, researcher of art philosophy, Fudan University)

Desktop, broken wood, height, wandering wave, creek, pig head, firefly, sleeping bag, tent, watermelon, building, mushroom, box, lantern, ruins, scavenger, backpacker, ignition, the floating earth

Lichen, fire watcher, tents undulating like mountains, branches and tendrils, a bunch of pedestrians walking in the wind in the night, crouched bird looking like a heart, water grass, green watermelon, purple night sky

——Li Jikai 1

Li Jikai sent these strictly illogical words and phrases to me before the opening of the exhibition, which, as he admitted, reflected his true feelings and real-life experiences in the process of preparing for the exhibition. The artist explained that, unable to express his ideas using complete sentences, he recorded fragmentary thoughts and random ideas. Although fragmented, in my opinion, those words and phrases might be the best annotations added to describe the exhibition.

Most of the works on display were created after the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan. Today, as the pandemic is still yet to end, it has continually panicked and frustrated people as it did during the previous lockdowns. This may not necessarily suggest what Li Jikai intended to describe and explain the rationale for his idea, however, to be honest, the artist could have been potentially motivated by it2. Even though watermelons, mushrooms, and tents consist of the most essential image motifs of the exhibition, they appear to be illogically connected in the strict sense. They represent what he saw by accident and what he felt at the moment. Coincidentally, those things are not conventionally referred to as everyday “necessities”, but as “an excess” in daily life. Li Jikai chose to look into them as his subjects neither because they define any fundamental concepts nor because they are secondary or marginally represented. Li Jikai never works out plans ahead for what and how he is going to paint; instead, he only follows his heart. The reason why he painted watermelons, mushrooms, and tents is that he was touched, at the moment, by their unique shapes and the particular setting.

As always, brush, acrylic, and linen canvas are all Li Jikai need for painting. The flexibility of the brush, the water-based nature of acrylic, and the texture of linen canvas allow him not only to enjoy the pleasure of “writing” but also to freely indulge in the transparent medium to articulate his genuine feelings and personal aspirations. Again, the ageless youth appeared in his paintings. Although things have changed as time goes by, his expression remains unchanged. In Li Jikai’s words, “as a bystander”, he is “constantly flashing amorous glances at the complex, cruel world”.3 Just like the flying fireflies in the paintings, he is reviving, lighting up the absurdity of the dark night, and guarding his own melancholy, perplexity, restlessness, and innocence.

[1] Courtesy of the artist, written on 10 April 2022.

[2] Wuhan has never been so quiet in my memory by Li Jikai, Fly further than the butterfly, Ding Ding Co., Ltd., 2020, P12-17.

[3] Li Jikai, quoted from Li Jikai’s World by Su Tong, With You Without You, Beijing Dialogue Space Gallery, 2011, P9.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo

Anthropomorphic Allegory of Summer

Oil on canvas

134 × 96.5 cm

©️Sotheby's

In the history of Western art, watermelon is a common motif. As early as the 17th century, fruits and vegetables were deemed enormously important subject matters in still-life paintings where watermelons were broadly portrayed. At one time, watermelons were, on the rare occasion, depicted independently; they were arranged together with various fruits and vegetables. Obviously, the main subject was the flesh of watermelons other than watermelon rinds. Italian painters, such as Giovanni Stanchi and Giovanni B. Ruoppolo, painted many still-life paintings of fruits and vegetables containing watermelons.4 Contrastively, Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s depiction of fruits, vegetables, and figures appeared to be more representative. The painter known for his grotesque Mannerist compositions oftentimes created portrait heads that were made entirely of objects such as fruits, vegetables, and animals. Such a style had been referred to as “bad taste” until it was rectified upon its rediscovery by Surrealist painters in the early 20th century. Unlike the precedented representations of fruits, vegetables, and/or landscapes, Arcimboldo’s fruits and vegetables solely functioned as components of the portraits with no indication of self-sufficiency. In a sense, however, in the case of Arcimboldo, functioning as an element that constituted the body, the vegetables, and fruits had been endowed with a distinctive liveliness; they constituted a sense of blasphemy and offensiveness against the prevailing Classicist paintings at that time.

[4] Although watermelon was a common fruit among the various fruits and vegetables depicted, it appeared to occupy a quite superior position in these paintings because of its volume and the bright colors of the flesh. Oftentimes, it was placed in dim-lit setting of landscapes, being coupled with a unique flash of light; all of this could easily set off a heightened light of the fruits and vegetables and the visualized sense of tastefulness to the audience. Such an artistic creation was not developed from field sketching. David Hockney, in his Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters (translated by Wan Chunmu et al as 隐秘的知识, Zhejiang People’s Publishing House, 2012), observes that part of the conception and painting came from on-site learning, it could have been built with the help of visual instruments such as a camera obscura, however, most of the background sceneries might be artificial in all likelihood. By placing vegetables and fruits in the setting of landscape, on the one hand, the idea was to give a sign of a turn towards naturalism or secularization. On the other hand, it was to show a sense of classicism and sacredness that remained in the paintings, which was evident in the triangular composition of vegetables and fruits as well as the mysterious scenery added in the background. In contrast, the fruits and vegetables, including watermelons, painted by the Dutch artist Abraham Brueghel displayed an enhanced sense of secularity.

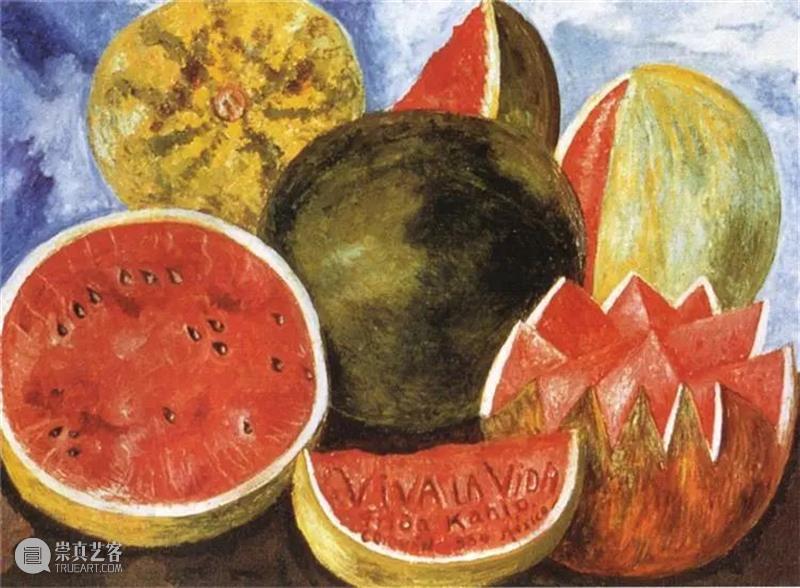

Frida Kahlo

Viva La Vida, Watermelons

1954

Oil on masonite

50.5 × 59.8 cm

cr. web

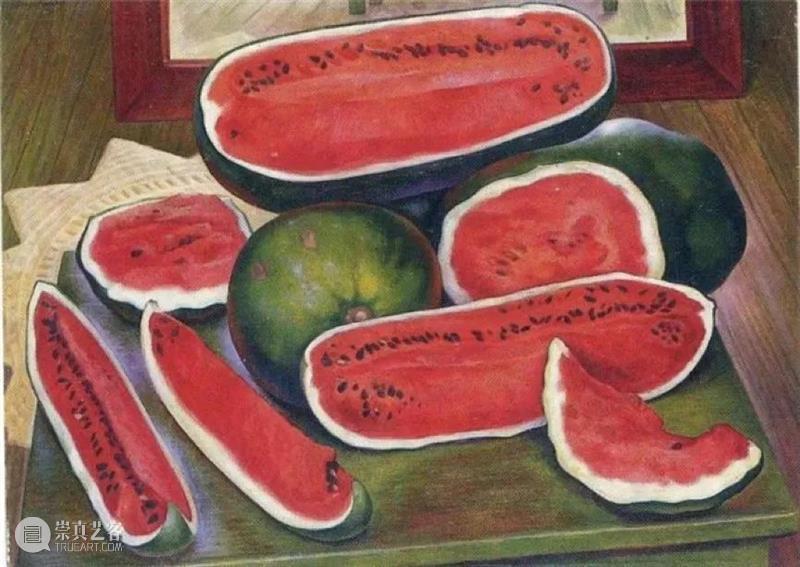

It was until the 20th century that watermelons were no longer attached to other things and become self-sufficient in the history of Western art. The Mexican painter Frida Kahlo’s last painting before she died was a still life of watermelons. The watermelons were painted in an orderly manner and took up a vast space of the picture. The vibrant red flesh and black melon seeds, together with the green rinds in different shades, provide a marked contrast, which allows the painting to suggest life and desire. The front segment in the foreground is labeled with “Viva la Vida” meaning long live life. The still life reiterates the double meaning of fragility and eternity suggested in the painting. It is worthy of note that the reason why watermelons are the subject is perhaps because watermelons, in Mexican culture, are inherently associated with despair and death.5 Three years later, Diego Rivera, Frida’s then husband, created a still life of watermelons in his final days before he died. The artwork can be understood as a “poetic response” to Frida’s final work; however, his painting appears to suggest a touch of gloominess and deadly silence.

[5] See Xiao Zhuang, The Watermelons that Save Your Life: What Watermelons Looked like in the Middle Ages, SOHU, https://www.sohu.com/a/333401320_119097.

Diego Rivera

The Watermelons

1957

Oil on canvas

68.7 × 92.7 cm

Cr.Dolores Olmedo Museum

In the history of Chinese painting, watermelons have been widely depicted, which were proclaimed by literati painters in particular. For example, as early as in the Yuan dynasty, Qiao Xuan created a watermelon that resembled an exotic animal with its mouth open in his “Picture of Vegetables and Fruits”. By the 20th century, Qi Baishi, Zhu Qizhan, Tang Yun, and Wang Senran among other ink wash painters depicted watermelons in various shapes and forms, all of which represented a sensibility of refined taste cultivated by literati painters. In contrast, Li Jikai’s paintings are more comparable to the good harvest of watermelons in propaganda posters. Li’s paintings are neither a bunch of fruits and vegetables that frequently appeared as still life nor a representation of the refined waste, they are simply a landscape composed of watermelon fields. The watermelons in Li’s paintings do not serve as a symbol of harvest and victory; the dull green rinds create a melancholy, dazed atmosphere. In this sense, Li’s watermelons are much the same as that of Frida and Rivera.

Qian Xuan

Vegetables and Watermelon

Scroll, color on silk

74 × 42 cm

Inscriptions: Yuan Qian Xuan Vegetables and Watermelon [题签:元钱选蔬果图 ]

Cr. web

Why watermelons? Perhaps, we can only get a clue from the round-headed boy that has been repeatedly present in Li’s paintings. Since the start of the last century, Li Jikai has continued to depict the figure to date. It’s been more than twenty years, and the artist himself is now in his forties, but the figure remains almost unchanged. Viewers may wonder why while the artist has become mature the boy depicted in his paintings seems to be the same: having a small body with a big, round head. He is either standing, lying down, or running; he rests his chin on his hand; he seems to feel awkward, and he even looks dazed and distracted. Li Jikai did not offer a definite answer or explain why he chose to paint the same figure repeatedly and why it remains the same as it was twenty years ago while the artist himself has aged. Possibly it is simply his subconscious or a feeling that pushes the idea, or, it may be a “condition” that he would fulfill.

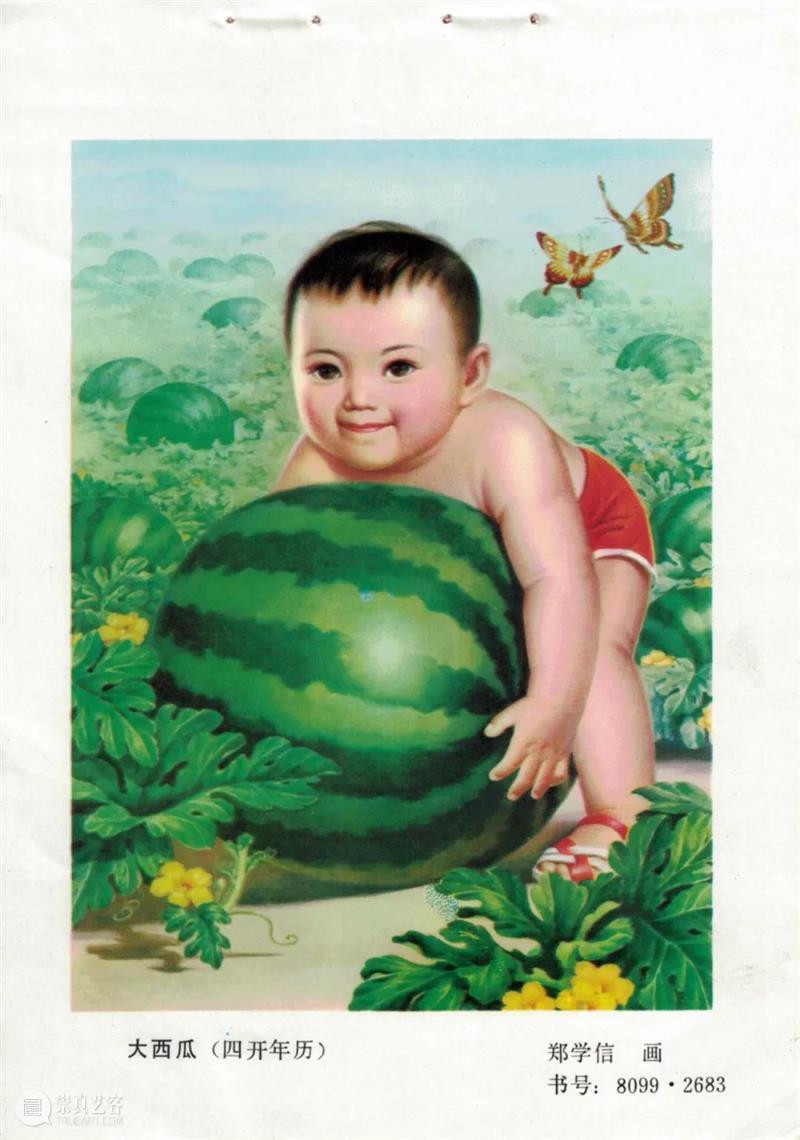

郑学信 Zheng Xuexin

大西瓜 The Big Watermelon

1983

年画 Chinese New Year paintings

The boy holding a watermelon has appeared in Li Jikai’s paintings time and again. In his most recent works “Watermelon Field” (2021) and “The Boy Resting in the Watermelon Field” (2022), the figure is seen to be holding a watermelon too, which has become a classic motif. A representative example is the New Year picture “Big Watermelon” by Zheng Xuexin, which was created in 1983 and widely circulated across China. The picture depicts a chubby little boy who’s trying to pick up a watermelon that is bigger than his head. With a round head and large eyes, the boy stares straight ahead, purses his lips, and smiles. How charming and innocent! How cute and lovely! The point here is that we may tend to imagine that the boy in the New Year picture created thirty years ago would have grown up as the watermelon-holding boy depicted by Li. Naturally, Li Jikai would not admit there is a close connection between the two figures anyways. What matters is that “Big Watermelon” provides us with a perspective and a point of entry into his artistic creation. For those who have lived through the 1980s, such a prominent image is nothing unfamiliar; in a sense, it has become a part of their upbringing. Possibly, the artist may have subconsciously integrated the image into his creation at the back of his mind when he decided to portray the subject matter. However, these two images are distinctively different, that being said, they may provoke different feelings. If Zheng’s “Big Watermelon” is suggestive of positivity and brightness, Li Jikai’s painting is rather indicative of negativity and bleakness. However, it is through the two images that we can catch a glimpse of very different times that the viewers have experienced from generation to generation. The artist himself also believes that those artworks are much more about the passage of time, social change, and the environmental and physical changes that individuals usually experience.6 Therefore, some viewers contend that Li Jikai has expressed a sense of confusion felt by individuals — the artist himself would also believe so, however, from a certain point of view, neither the boy in “Big Watermelon” nor that of Li Jikai’s painting represents an individual, the image rather represents a generation — even though we would also see the boy created by Li Jikai as a portrayal of ourselves. While holding a watermelon and staring at the watermelons in the field, the boy in “Watermelon Field” appears to be thinking about something and feeling lost at the same time. In “The Boy Resting in the Watermelon Field”, the boy’s expression reveals a sense of melancholy when he is leaning on a watermelon and lying in the field.

[6] Source: an interview with the artist published in National Arts (国家美术), https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/QvUz_fPcN8rD6rCQJPKLHw

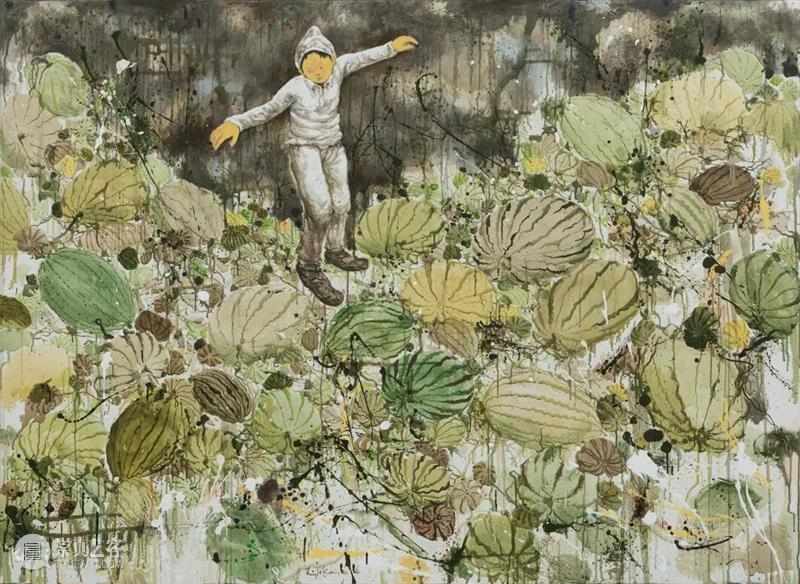

Li Jikai

The Boy Resting in the Watermelon Field No.2

2022

Acrylic on canvas

60 × 200 cm

Li Jikai

Watermelon in Dark Night

2022

Acrylic on canvas

145 × 200 cm

Different from the earlier-mentioned paintings, “Watermelon in the Dark Night” depicts a boy wearing a hoodie who appears to be terrified when staring straight ahead uneasily. He seems to be dancing, and the painting has captured the instant he was about to fall. Meantime, the black background creates a dark, misty atmosphere. The composition and the presentation of the painting remind me of Li’s previous work that has a similar title, which is “Standing in the Dark Night” (2016). The boy in the painting with a similarly gloomy background stares in horror at the scattered skulls on the ground. Certainly, we can think of the watermelons on the ground as a symbol of vigorous vitality, meantime, what it suggests is that the watermelon in the case is a metaphor for head or death. In this sense, it is more likely to be a reinterpretation of Frida and Rivera’s paintings of watermelons and what they symbolize. In my opinion, the movement of the boy in Li Jikai’s painting also suggests a critical state where we cannot confirm whether the painting is indicative of death or a new life as if there is an abyss at the back and the road ahead is full of uncertainties and fear.

Li Jikai

Standing in Darkness

2016

Acrylic on canvas

32 × 32 cm

Such a critical state has been accurately reflected in his method of painting. As mentioned earlier, Li is good at using brush and acrylic. While the flexibility of the brush (in addition to his fascination with texture) is apt to depict/write the texture of the watermelon rind patterns, the water-based nature of acrylic shows its unique advantages that can allow the exterior rinds to be accurately portrayed on the one hand and enable the vulnerability of the outer shells to be fully depicted on the other hand thanks to the semi-translucency of the pigment. In particular, the traces of the dripping pigments, either intentionally or unintentionally, can be understood not only as stems and branches that grow wildly but also as an “artistic force” that goes beyond/ is independent of images and forms. In Hal Foster’s words, such is a “philosophy of the remainder”—of the “recalcitrant detail, the personal punctum, the traumatic real”.7 However, this fascination can lead to an occlusion of reality, also a provocation of another underlying reality of truth.

[7] “Hal Foster on Ed Atkins’s The Worm” (in Chinese as哈尔·福斯特谈埃德·阿特金斯的〈虫〉), trans. by Feng You, Art Forum (Chinese), published on 5 October 2021. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/quYs07gDmcDb0wg7KutABA

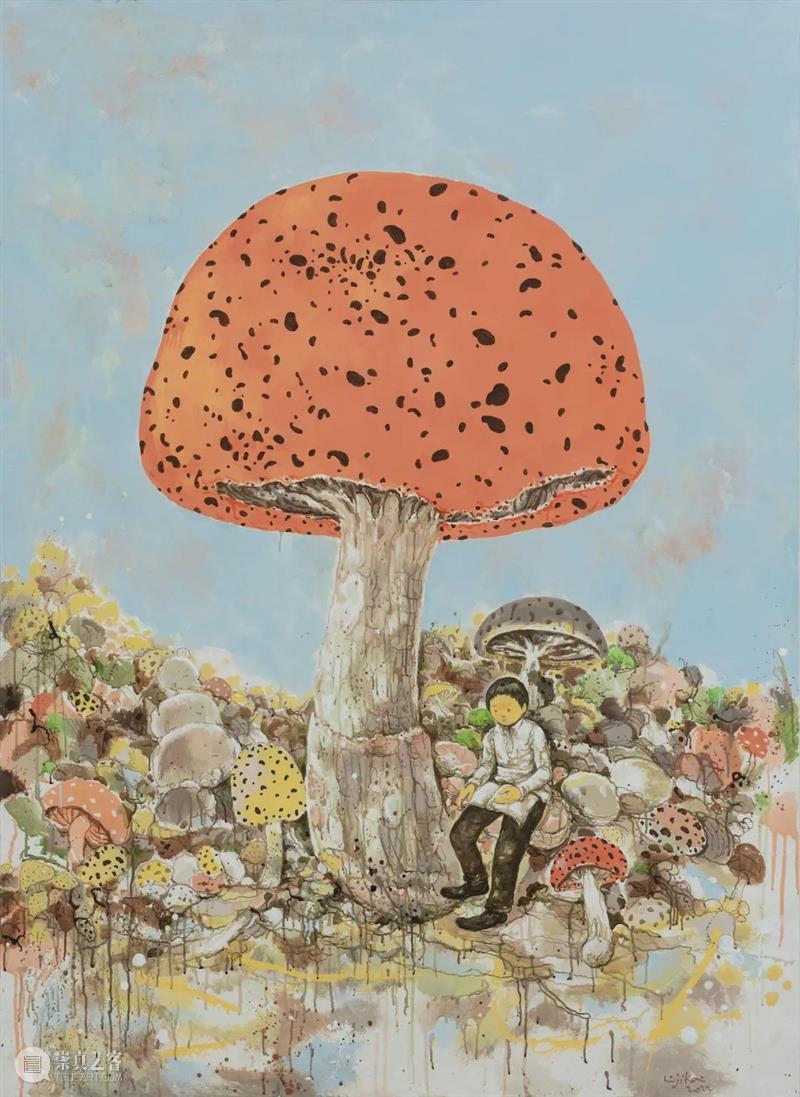

In Li Jikai’s another series “Mushrooms” where there appears to be a new resting place, watermelons have been replaced by mushrooms. Different from the “Watermelon” series, what Li Jikai depicted in the “Mushrooms” series was not the mushrooms that he saw with his naked eyes but the “giant mushrooms” and/or “super mushrooms” that had been mutated in his imagination. Those mushrooms rather resemble towering trees with slender branches topped by a giant umbrella-like cap. Unlike the mushrooms that grow in the dark and damp forest among grasses where humus is formed in soil, Li’s mushrooms grow in the middle of a dry desert. The bright and transparent sky in the background seems to remind us that they are more likely to be exposed to sunlight other than growing in the dark and damp places. Just like those giant mushrooms, such a fictionalized account of the unnatural growth perhaps originated from the artist’s imagination, which means that the artist did not see the mushrooms as real mushrooms in the first place.

Li Jikai

Giant

2019

Acrylic on canvas

205.5 × 185.5 cm

The reason why he chose such a theme, according to Li Jikai himself, is that he discovered that the plump, rounded shape of mushrooms was quite similar to a boy’s image in his imagination. The small mushroom heads and stones on the ground were also stylized as children’s faces. Although most of the big mushrooms are where the boy leans, mushrooms have gone beyond an object of nature. In other words, the mushrooms in Li’s paintings are an embodied, personified existence. This reminds me of the “Giant” series created by the artist in 2019. The composition of the figures is obviously influenced by Georg Baselitz: the giant physique with a small head together with the looking-up perspective clearly highlight the grandness and absurdity of the “mutated” body. In addition to that, the whole body has a quite unique composition, as if it is piled up by stones or sandbags of varied shapes and sizes or covered with a self-made bloated “armor”. I would say, such is an alienated form of life that cannot be named or categorized. With this, we might consider the “big mushrooms” as a variant of the “giant” - which here is some kind of psychological projection of the young man in the painting.

If the artist's depiction of the “giant” is a presentation of the boy that projects his feelings onto the painting as every young person has/had a fantasy or dream of becoming a giant. Perhaps in the artist’s subconscious, it is his distinct to depict “giants” as a way of ensuring safety. Similarly, the boy resting under the big mushroom seems to have a sense of safety. The difference, however, is that while the big mushroom, as a figurative giant, functions as a representation of the boy’s feelings, the giant can be seen as an ideal incarnation of the boy even though the big mushroom is independent of the boy. That being said, such a surreal, fictionalized depiction is by no means a simple representation of material dependence.

Li Jikai

The Boy & Big Mushroom

2022

Acrylic on canvas

147 × 270 cm

In “The Boy and Big Mushrooms” (2022), two giant mushrooms grow towards each other. Being wrapped around one another, the evolves seem to form an inverted triangle. In the foreground, the boy leaning against the stipe looks straight ahead as if lost in thought. This appears to be a daydream scene of an autistic person — as suggested by the yellowed face and his hands — who imagines himself becoming a giant mushroom so as turn into a thriving creature. It is possible that the artist saw the mushroom as a part of the boy’s body, that is, the external male genitalia. In a sense, this is evident in the shape of the mushrooms. However, the difference is that the phallus here is a proper name, a “feigned” signifier. The phallus simply resembles a penis; however, it has been worshipped because of the function of the reproductive system.8 In this sense, “mushrooms”, like “giants”, are a phallic symbol of self-worship. In “Mushroom and the Boy who is Reading” (2022), a boy is depicted to be reading under a huge tree-like mushroom. We have no clue about what the boy is reading, but what we cannot deny is that reading could be a process of imagining and comforting oneself. In addition, I would argue that it hints at an inner tension between sexual arousal and repression; in other words, what the painting reveals is the instant that the boy is in a trance-like state of sexual awareness.

[8] Chih-chung Shen, A Gleam in Eternal Night: Lacan and the Unending Revolution of Psychoanalysis, Taipei: National Taiwan University Press, 2019, p. 422.

Li Jikai

The Mushroom & the Boy Who Reads

2022

Acrylic on canvas

200 × 146 cm

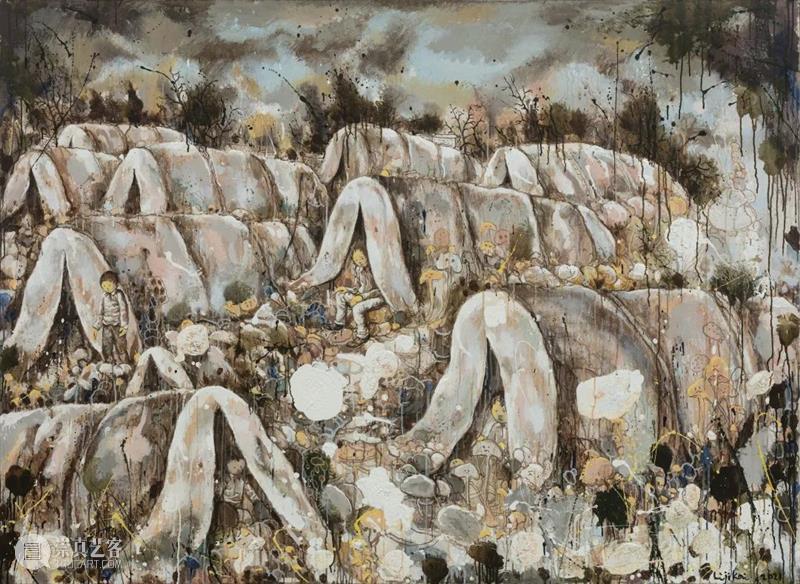

Only from a psychological perspective can we understand the corresponding series “Tents” recently created by the artist. In “The Tents Undulated Like Hills” (2021), there is a scatter of tents on a mountain slope; the scattered tents look like rolling hills where the color of the tents integrates with the color of the ground. With a unique technique, the artist deliberately constructed the tents that resemble mushrooms in terms of shape and texture. Such a technique enables the tents to be characterized by a distinctive embodiment and vitality. Like a row of giant reptiles, those tents being scattered one by one appear to be lying on a slope. As evident in “Lichens— Tents”, another work from the same series, the artist sees tents as lichens. Lichens, in fact, grow only on the surface, however, in Li Jikai’s paintings, lichens are inseparable from soils, it is a part of the land.

However, neither for the artist nor for the viewers, the land and “lichens” perhaps are no longer objects being represented, they are rather autonomous subjects. As evident in the shape of the entrances of the tents, they are an embodiment; if the mushrooms in the “Mushrooms” series embody a sexual reference, i. e. male genitalia, the tents in this series clearly embody the female genitalia. To put it another way, the two embodiments constitute a yin and yang relationship. This is also evidenced by the overall atmosphere of the paintings. While the “Mushrooms” series suggests a sense of transparency and brightness, the “Tents” series highlights a sense of darkness and gloominess.

Li Jikai

Tents of Rolling Hills

2021

Acrylic on canvas

146 × 200 cm

The boy that looks distinctly familiar appears in the “Tents” series too, either lying outside the tent or lying at the entrance of the tent; and in some cases, he is invisible, perhaps he hides himself inside the tent. Like the giant mushrooms, the tents are also the boy’s resting spots; stepping into the tents simply means he has returned to Mother Earth, which is, for him, another way of having a sense of safety. It is also at this point that the two series and the “Watermelons” series inherently create a connection and a difference at the same time; that is, if the artist ever put the boy in a dangerous situation where there were voids and confusion, then the idea of the “Mushrooms” and “Tents” series was to find a safe, reliable place that would provide shelter. Either way, the artist’s inner world has been genuinely reflected.

As we have gone through the three above-mentioned series, we may now have a more thorough understanding of the “ageless boy” and the “giant boy” created by Li Jikai. For him, such a unique image is not simply a description of an individual’s memories but rather a depiction of a generation’s collective psychological experience: being fragile and sensitive, that means giants cannot hide their anxieties and fears even if they have been “successfully” transformed into giants. This way, Li made up a world of innocent fairy tales and allowed the negative emotions experienced by himself (or perhaps the whole generation), that is, feeling empty and self-aggrandizing. It is precisely in this process that Li constantly deals with the relationship between himself (his life and work) and reality. In doing so, he may have realized that returning to the basic desires and fundamental needs perhaps is a most essential, critical way of living. To put it into his own words,

Hiding in the corner, switching into a living/working mode where material needs are minimized,

insignificant human beings living on an insignificant speck of dust,

as if impossible to catch up with the times.

In painting, I experience, I feel, and I explore possibilities.

Constant frustration in the process of making art keeps us away from all the complacency.

In painting, either working too hard or lacking honesty makes people feel that they are the ultimate losers.

The significance of the creative labor is that one can silently listen to their own breath and leave traces of lives that they have lived.

The failures in everyday life can lead our hopes to being turned to dust.

Only when being given less choice can one create paintings in a more honest, effective manner. 9

[9] Courtesy of the artist, April 10th, 2022.

关于艺术家

李继开

1975年生于四川成都。1999年毕业于四川美术学院油画系。2020年毕业于中国艺术研究院美术学专业,获博士学位。现任教于湖北美术学院。

其作品曾于中国美术馆、北京今日美术馆、上海龙美术馆、上海民生美术馆、上海当代艺术馆、美术文献艺术中心等重要机构展出,也曾于英国、美国、德国、瑞士、荷兰、日本、韩国等海外各国展出。亦被北京今日美术馆、上海龙美术馆、深圳何香凝美术馆、广东美术馆、湖北美术馆、武汉美术馆、新加坡MoCA、伦敦Franks-Suss收藏等国内外重要艺术机构与私人所收藏。

RELATED LINK

关于画廊

偏锋画廊坚持对中国当代艺术进程的洞察以及对欧洲及战后艺术大师的探索,并在两者的对话与碰撞中寻找各种可能的艺术力量。偏锋既是中国最早推动抽象艺术研究与发展的重要画廊,也是持续探讨具象绘画在当下多种可能性的主要机构。我们深信,艺术的体验产生于一个又一个的变革中创造的新世界;艺术家的作品正是探索世界的第三只眼睛。对于收藏家,偏锋为其提供专业知识,鼓励他们发掘个人独特的视角,只因两者的充分结合才能构建卓越的收藏。我们希望更多的藏家可以秉持鉴赏家的心态,更深入地理解当代艺术以及欣赏画廊发掘、重塑并坚信的艺术家。

About the Gallery

PIFO Gallery concentrates on the participation of the course of Chinese contemporary art and the exploration of post-war European master artists and seeking for all possibilities of art power in the dialogue and collision between the two aspects. As a major gallery in China specialized in the study and promotion of abstract art, and also the main institution to continuously explore the various possibilities of figurative art at present, PIFO is convinced that the experience of art emerges from the new world created by one revolution after another; The artist's work is the third eye to explore the world. For collectors, PIFO provides expertise and encourages them to explore their own unique perspective because only the combination of the two can make a great collection. We hope to see a growing number of collectors to take on the roles of a connoisseur, with a more in-depth understanding of Asian and Western contemporary art, and appreciate the artists discovered, reshaped and firmly believed in by the gallery.

媒体 / 图片垂询

Press enquiries/images

张梅颖 Mabel Zhang

mabel.zhang@pifo.cn

T: +86 10 59789562

其他垂询

All other enquiries

王彧涵 Sophia Wang

sophia.wang@pifo.cn

M: +86 18210011135

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享