图片局部已被打码处理,原作无

original works are without mosaic

图片局部已被打码处理,原作无

original works are without mosaic

2012年北京的冬季,我采访了林天苗——她常被描述为中国仅有的几位女性主义艺术家。她很直白地告诉我:中国不存在女性主义。那是西方的东西。1她的意思是,我认为,欧美的女性主义和中国女性的经历相关性并不大——而且她拒绝被父权社会主导的中国艺术界归类为“女性艺术家”。正如学者崔淑琴所说,“很少有中国女艺术家愿意被贴上女性主义的标签,即便她们作品中女性主义的痕迹非常明显。”2 然而,很多艺术家使用性别的议题去挑战反常规的思维成见。3 女性主义的自我认同不是特别重要,就像艺术史学家Joan Kee所说的,“问题不在于亚洲女性艺术家将自己归类为女性主义艺术家,或者她们的创作被赋予女性主义的讯息,而在于用什么逻辑进行解读。”4 女性主义在中国很多当代艺术家的创作中都有所体现,只是呈现方式比较微妙并且承载了特定的文化寓意——即便她们不愿意承认女性主义的标签。我和跨学科艺术家曹雨以及廖逸君采访,她们对于被归类也持保留意见,但是她们的作品强有力地挑战了“女性主义”的本质。

曹雨:女性主义和祖先崇拜

Cao Yu: Feminism and ancestor worship

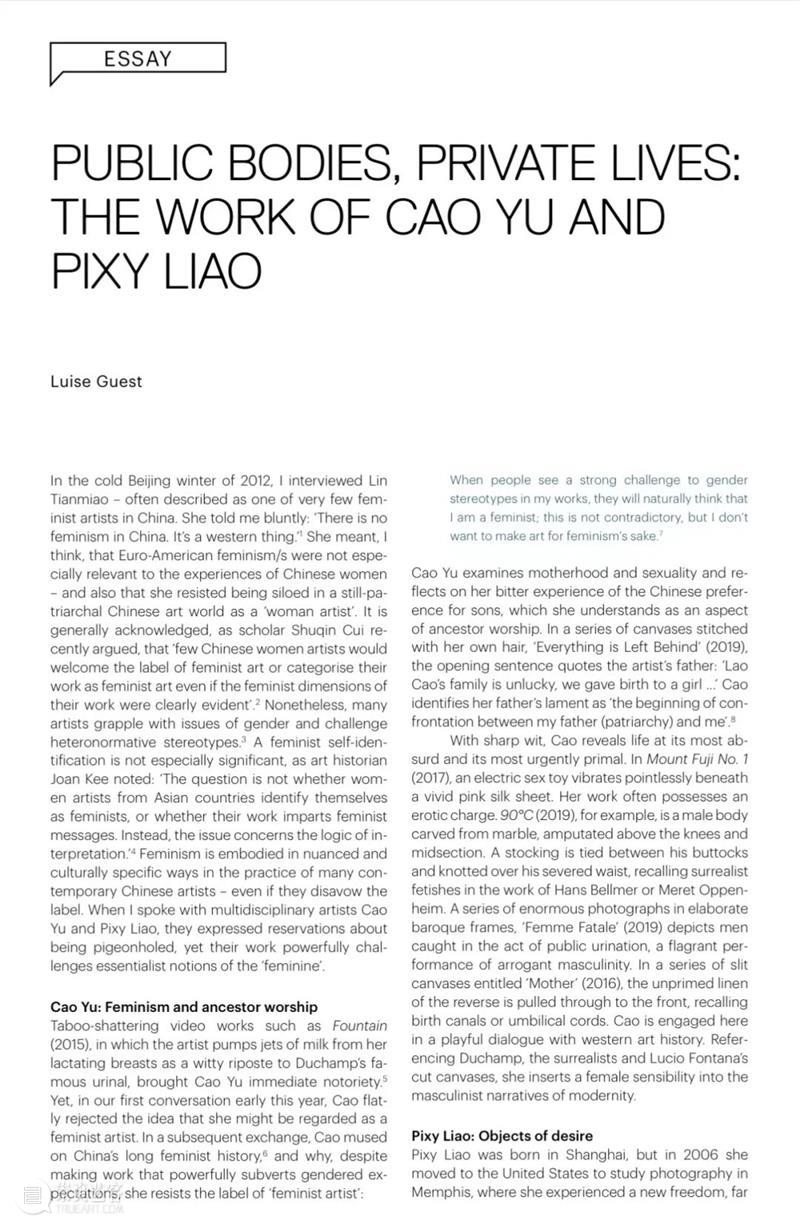

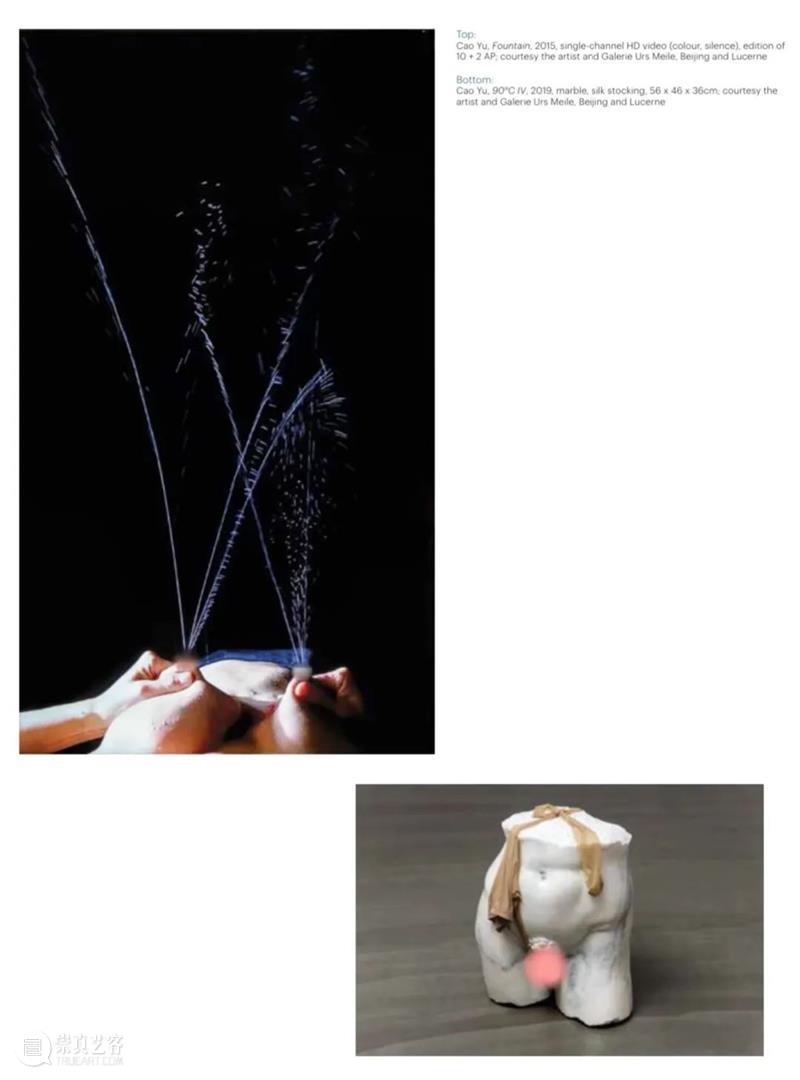

在其令人震惊的图腾般的影像作品,比如《泉》中,曹雨挤捏着自己哺乳期的乳房,纯白色的乳汁喷射而出,她的作品机智地回应了杜尚著名的小便池作品,这件影像作品很快让曹雨声名大躁。5 然而,在我们2020年初的第一次对话中,曹雨直白地拒绝了女性艺术家的标签。在接下来的交流中,她对中国长期以来的女性主义历史进行了深入思考6,以及为什么尽管她的作品强有力地颠覆了性别期待,但是她依然拒绝被贴上“女性主义艺术家”的标签:

Taboo-shattering video works such as Fountain (2015), in which the

artist pumps jets of milk from her lactating breasts as a witty riposte

to Duchamp’s famous urinal, brought Cao Yu immediate notoriety.5 Yet, in

our first conversation early this year, Cao flatly rejected the idea

that she might be regarded as a feminist artist. In a subsequent

exchange, Cao mused on China’s long feminist history, 6 and why, despite

making work that powerfully subverts gendered expectations, she resists

the label of ‘feminist artist’:

“人们在我的作品中看到了对性别既定期许强烈的挑战时,会自然而然认为我是女权主义者,这并不矛盾,然而我做艺术并不想为了女权而女权。”7

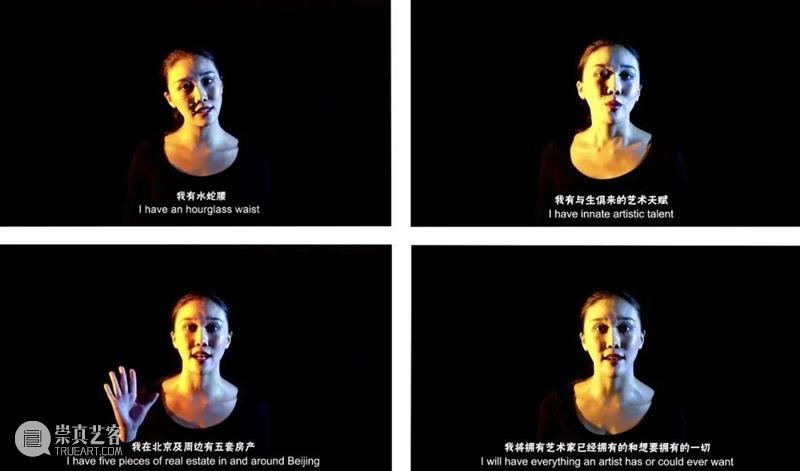

Cao Yu, I Have, 2017, single-channel HD video (colour, sound), 4'22", film still

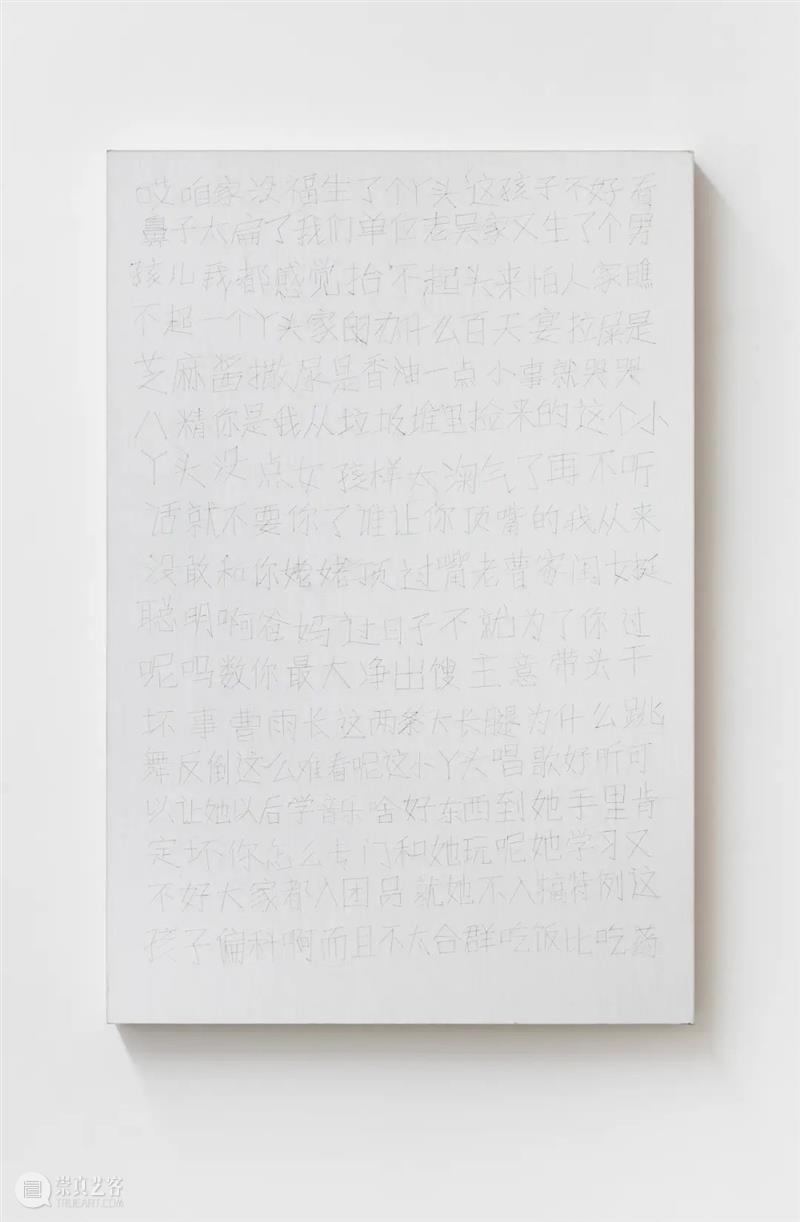

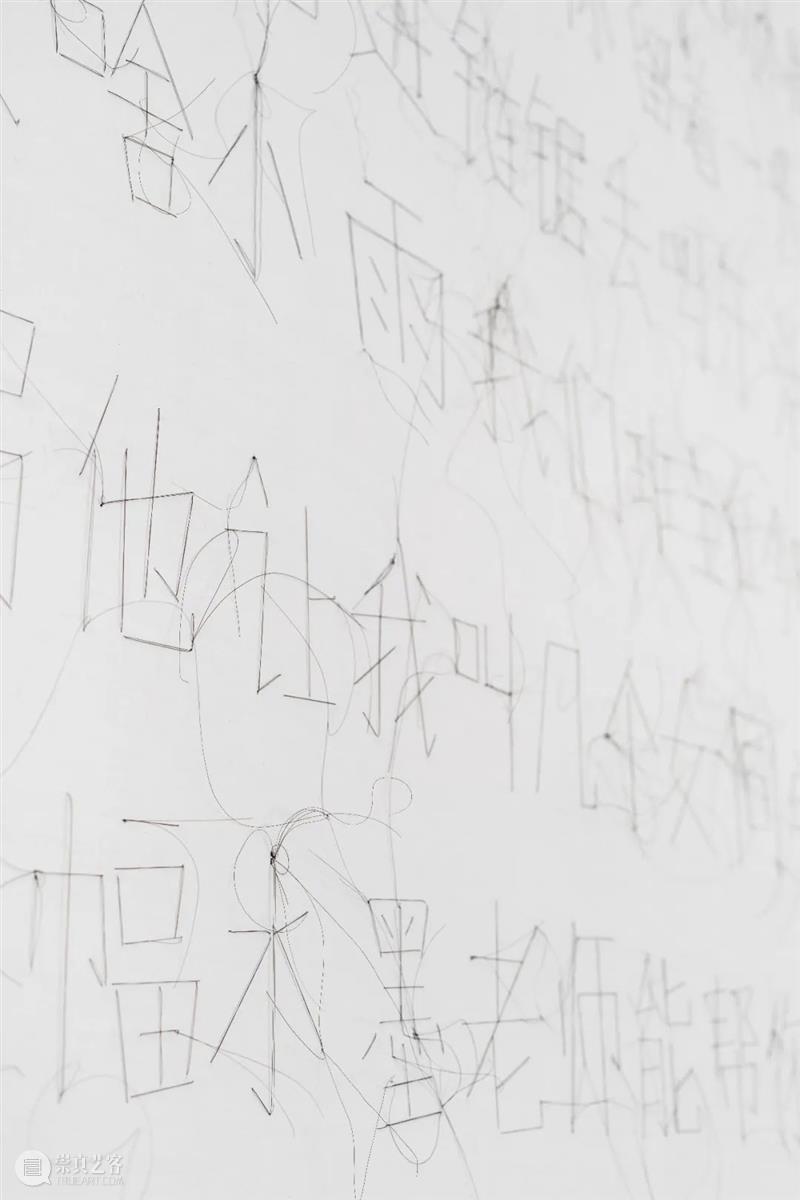

曹雨探讨了母性和性别的主题,并反思了她有关中国人对儿子的执念——在她看来这是祖先崇拜的一个方面——的痛苦回忆。她用自己的头发在画布上绣成文字,创作了“一切皆被抛向脑后”(2019)系列作品,开篇第一句话引用了曹雨的父亲的话:“哎,咱家没福,生了个丫头……”曹雨把父亲的这句叹息视为“父亲(父权制)和我冲突的开始。”8

Cao Yu examines motherhood and sexuality and reflects on her bitter experience of the Chinese preference for sons, which she understands as an aspect of ancestor worship. In a series of canvases stitched with her own hair, ‘Everything is Left Behind’ (2019), the opening sentence quotes the artist’s father: ‘Lao Cao’s family is unlucky, we gave birth to a girl ...’ Cao identifies her father’s lament as ‘the beginning of confrontation between my father (patriarchy) and me.’8

曹雨,《一切皆被抛向脑后》,局部

Cao Yu, Everything is Left Behind, detail

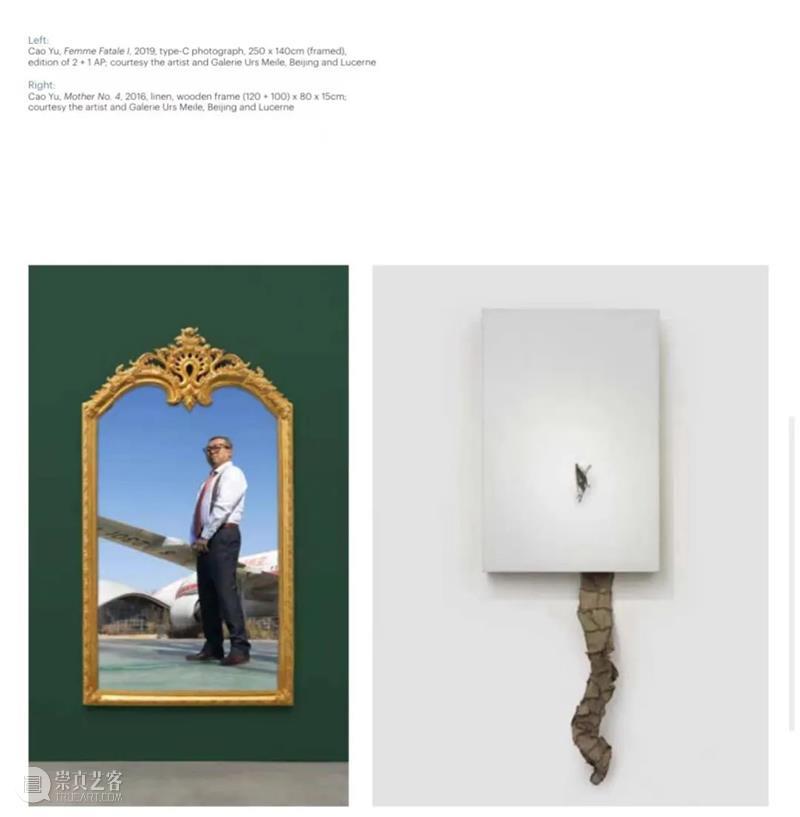

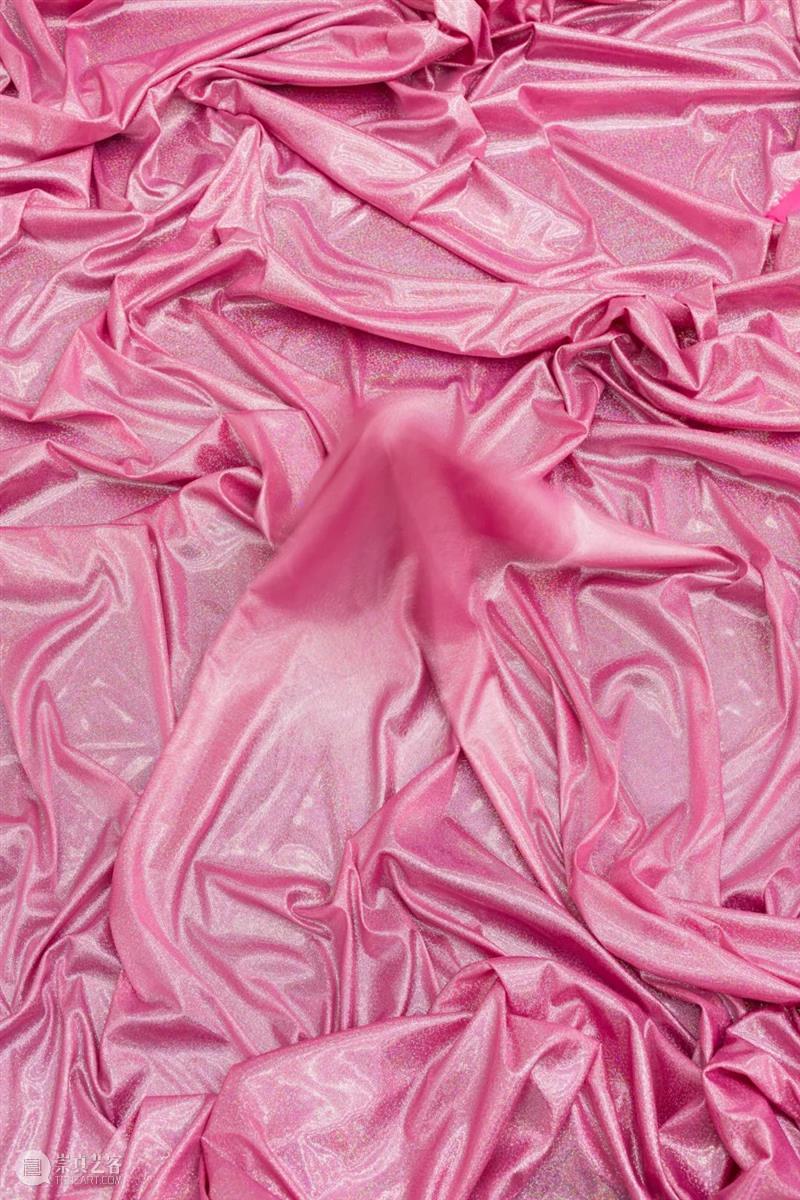

曹雨,《尤物》,2019,c-print, 像框

Cao Yu, Femme Fatale, 2019, c-print, frame

Cao Yu, Mother No. 4, 2016, linen, wooden frame, (120 + 100) x 80 x 15 cm

Cao Yu, Mount Fuji, 2017, electric sex toy, silk sheet, dimensions variable

1.作者2012年发布于The Culture Trip网站的与林天苗的采访,2016年以新的形式发布:https://theculturetrip.com/asia/china/articles/no- feminism-in-china-an-interview-with-lin-tianmiao/,最后一次登陆时间:2020年11月2日

The author’s 2012 interview with Lin Tianmiao for the websiteThe Culture Trip was republished in a new format in 2016: see https://theculturetrip.com/asia/china/articles/no- feminism-in-china-an-interview-with-lin-tianmiao/, accessed 2 November 2020.

2.崔淑琴,“Introduction: Why (en)gender women’s art?”,positions: asia critique,第28卷,2020年第一期,第6页

Shuqin Cui, ‘Introduction: Why (en)gender women’s art?’,positions: asia critique, vol. 28, no. 1, 2020, p. 6.

3. Monica Merlin表示关于21世纪头十年的中国女性主义艺术的学术探讨与艺术家的作品并没有同步,参考:“Gender (still) matters in Chinese contemporary art”, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, 第六卷,2019年第一期,第 5–15页。

Monica Merlinargues that scholarly investigation of Chinese feminist art in the first decades of this century has not kept pace with the work of artists: see ‘Gender (still) matters in Chinese contemporary art’, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, vol. 6, no. 1, 2019, pp. 5–15.

4. Joan Kee, ‘What is feminist about contemporary Asian women’s art?’,发布于展览画册Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art, 纽约布鲁克林博物馆,2007,第107页。

Joan Kee, ‘What is feminist about contemporary Asian women’s art?’, in Global Feminisms: New Directions in Contemporary Art, exhibition catalogue, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 2007, p. 107.

5.《泉》(2016)是曹雨于中央美院毕业展展出的作品,这件作品让人感到被冒犯并招致警告。学校的很多教职人员和观众认为它是色情作品,并试图将其从展览中撤除。曹雨的名字也被从获奖提名名单中被去除,观众对这件作品往往表示鄙夷和震惊。从那之后,这件作品在麦勒画廊北京展出,这个画廊也是曹雨目前的代理画廊,2017年该作品在悉尼的艺术空间The Public Body .02’中展出。

Fountain(2016) was exhibited for Cao Yu’s MFA graduation exhibition at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts. It caused what might best be described as affront and alarm. Many faculty members and visitors considered it to be pornographic, and attempts were made to remove it from the exhibition. Cao Yu’s name was withdrawn from a nomination list for a prize, and visitors often expressed disgust and shock. Since that time the work has been shown in Cao Yu’s solo show at Beijing’s Galerie Urs Meile, which represents her, and also in 2017 at Sydney’s Art space in ‘The Public Body .02’.

6.中国的女性主义理论和实践起源于晚清时期,20世纪初随着西方当代主义的影响——在共和国时期、五四运动时期以及新女性崛起——而加速。女性和他们同时代的男性们竞争获得受教育权和投票权。重要的女权主义者包括穿男装的革命烈士秋瑾(1875-1907年),她呼吁推翻旧王朝,呼吁女性解放,并因此被处死;还有一位重要的无政府主义女权主义者是作家何殷震,1907年,她的文章《女子解放问题》以及《女子复仇论》于2013年首次被译成英文,Lydia H. Liu,Rebecca E. Karl和Dorothy Ko(编),《中国女权主义的诞生》,纽约哥伦比亚大学出版社

Feminist theory and practice developed in China in the late Qing dynasty; it accelerated in the early twentieth century with western modernist influences during the Republican period, the May Fourth movement and the creation of the xin nüxing (new woman). Women fought alongside their male peers for the right to education and to vote. Significant feminists included cross-dressing revolutionary martyr Qiu Jin (1875–1907), whose advocacy of dynastic overthrow and female emancipation resulted in her execution, and anarcho-feminist writer He-Yin Zhen who published ‘On the Question of Liberation of Women’ and ‘On the Revenge of Women’ in 1907, translated into English for the first time in 2013: Lydia H. Liu, Rebecca E. Karl and Dorothy Ko (eds), The Birth of Chinese Feminism, Columbia University Press, New York.

7.作者和曹雨于2020年5、6月进行了首次采访,文章于9月1日发布于燃点网站《展示与讲述:曹雨的性别化象征》。2020年10月,该采访之后的几个星期我们又通过微信和电子邮件进行了沟通。曹雨用中英文进行的回复。文中的引言出于简洁和符合情理的考虑酌情进行了编辑。

The author first interviewed Cao Yu in May/June 2020 for an article published byRandian on 1 September 2020, ‘Show and tell: Cao Yu’s gendered embodiment’. See www.randian- online.com, accessed 2 November 2020. This interview was followed-up with a conversation via WeChat and email over several weeks in October 2020. Cao Yu responded in both English and Chinese. Quotes have been lightly edited for brevity and sense.

8.同上。

ibid.

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享