《刘索拉》展览现场,元典美术馆-北京,2023

The Exhibition view of Liu Sola, Yuan Art Museum-Beijing, 2023

刘索拉的活乐谱

Liu Sola’s Animated Scores

像任何一位音乐学院培养出的作曲家一样,刘索拉熟悉传统谱曲,但是这次展览的乐谱看起来更像视觉艺术,而不是一种音乐符号。那么除了看上去不同寻常,这些她早在1997年就开始制作的乐谱还有哪些可以探究的层面?以下是可供参考的4点:

Like any conservatory-trained composer, Liu Sola can write conventional scores, but the scores at this exhibition look more like visual art than a form of music notation. Besides being unusual, what else is there in these scores which she started producing in 1997? Here are 4 points among others to consider:

《形非形》,刘索拉,纸,1999

In-corporeal, Liu Sola, paper, 1999

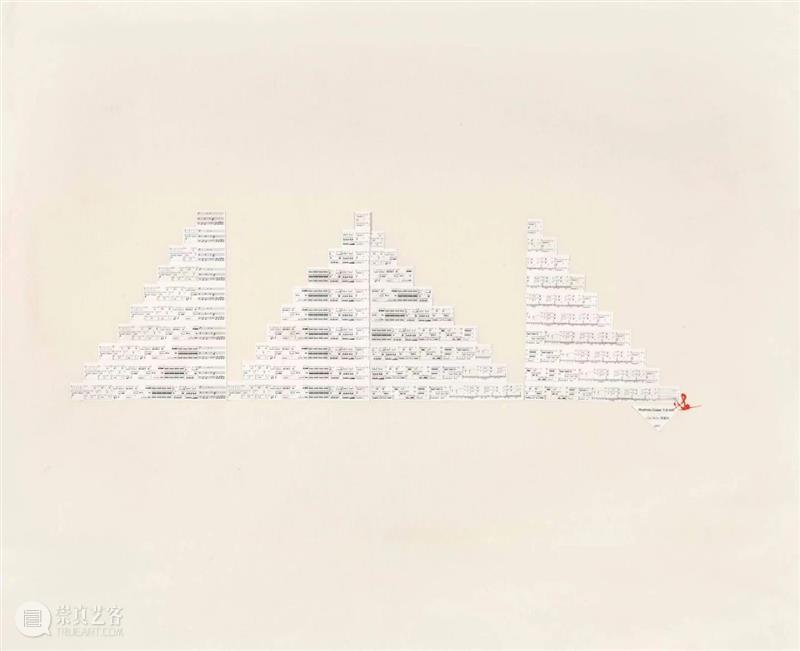

--“忘记之前所学”的过程

--A Process of “Unlearning”

索拉在国外作为作曲家和表演艺术家生活工作了15年,先是在伦敦,然后在纽约,在那里她吸收了许多关于当代音乐和自由爵士的新思想。然而,当她在2000年初回到中国,与中国音乐家合作创作中国音乐的时候,她开始了一个新的过程,与其说是将国外所学到的应用于未来的作品,不如说是将自己从之前所学中解放出来:“忘记之前所学”是一个充满悖论的创作过程。一个重要的步骤是恢复音乐的形体。

Sola spent 15 years abroad living and working as a composer and performer, first in London and then in New York, where she absorbed a lot of new ideas about contemporary music and free jazz. However, when she returned to China in the early 2000’s to work with Chinese music and musicians, she began a process not so much of applying what she had learnt abroad to her future work, but more a process of freeing herself from what she had learnt: “unlearning” as a paradoxical creative process. An important step was to restore body to music.

《大圣传奇》,刘索拉,纸,60 x 30 cm,2022

The Legend of Monkey King, Liu Sola, paper, 60 x 30 cm,2022

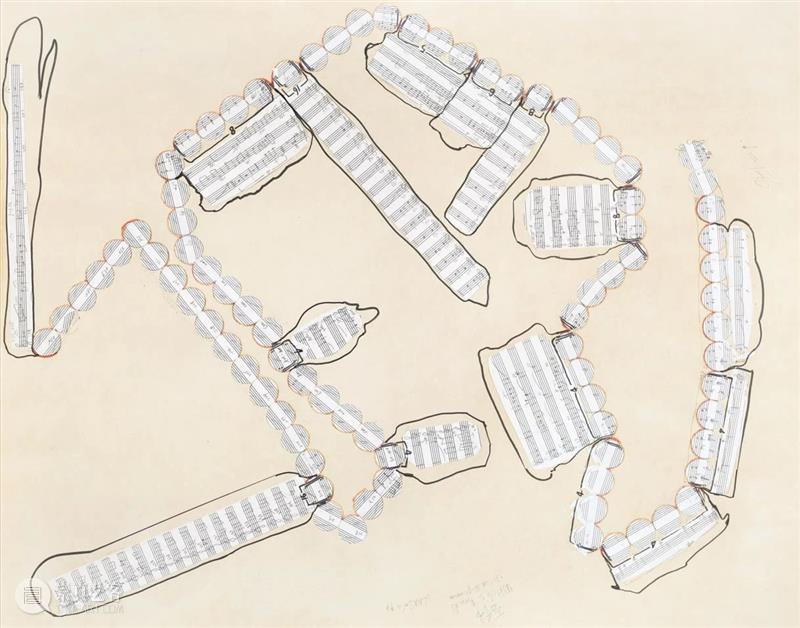

--生成-形体

--Becoming-Body

面对这些乐谱,我们首先注意到的是它们是多么生动有趣,多么不似抽象符号。这意味着音乐也是一种物体,这个“物体/音乐”对眼睛的作用不亚于对耳朵的作用。有些乐谱,如“爸爸椅”,甚至采用可辨识的物体形状,而其他的乐谱则不易辨识。音乐要求我们以全身来体验,而不仅仅是用身体的某一部分。【索拉是法国哲学家吉尔·德勒兹(Gilles Deleuze)的读者,尽管她是一位古怪的读者!】这些活乐谱向我们展示了,正如德勒兹可能观察到的那样,乐谱生成了形体。这在与音乐有亲密联系的画家保罗·克利(Paul Klee)作品中也有着突出的体现。克利将线条称为去散步的点,而不是抽象实体;也就是说,线是点生成的形体。

The first thing we notice about these scores is how animated and playful they are, how unlike abstract notation. The implication is that music is also an object, and object-music addresses the eye as much as the ear. Some scores, like “Daddy’s Chair”, even take the shape of identifiable objects, while others are less easily identifiable. Music requires us to use the whole body and not just a part. (Sola is a reader of the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, though an eccentric reader!) These animated scores show us, as Deleuze might observe, scores becoming-body. A similar emphasis can be found in Paul Klee, a painter with an intimate relation with music. Klee speaks of a line not as an abstract entity but as a dot going on a walk; i.e., the line as the dot becoming-body.

《节奏密码》,刘索拉,纸,98 x 84 cm,2007

Rhythmic Codes, Liu Sola, paper, 98 x 84 cm, 2007

--如同一套乐高玩具

--As Lego Set

一套乐谱还可以启示我们该如何看待音乐和我们所生活的世界。古典乐谱将音乐记为水平音符和垂直和弦之间的关系,而横轴和纵轴同步的能力反映了一个有序而等级分明的世界。我们可以把十二音体系音乐这种不同寻常的作曲法的引入看作是对一个不协调世界的直觉的反应;一个抛弃了横轴和纵轴的无调性音乐;一个以偶然性、不确定性和失序为特征的音乐。尽管如此,无调性音乐现在已经成为“当代音乐”的体系,而恰恰在这一点上,孩子们玩的乐高玩具套装可以看作是对索拉乐谱亦庄亦谐的模拟。乐高是由一个个独立部件组成的模块化系统,这些部件的组合允许我们创造任何我们可以想象的东西。在索拉趣味十足的乐谱中,音符不必以标准的方式强制相互跟随;它们可以跃线或进行“量子飞跃”。这些乐谱向我们揭示了音乐既精确又不可预测的特性。

《压缩》,刘索拉,2017, 2021年元典美术馆-北京展览现场

Compress, Liu Sola, 2017, The exhibition view of Yuan Art Museum–Beijing, 2021

A music score can also give some idea of how we think about music and the world we live in. The classical score notates music as the relation between horizontal notes and vertical chords, and the ability to synchronize the horizontal and vertical axis reflects an orderly and hierarchical world. We can think of the introduction of 12-tone music which is scored very differently as the intuition of a world out of sync; an atonal music that abandoned the horizontal and vertical axis; a music marked by chance, indeterminacy, and the loss of order. Nevertheless, the atonal has now become the system of “contemporary music”, and here is where the idea of the Lego set that children play with suggests itself as a half-serious analogue for Sola’s scores. Lego is a modular system consisting of independent parts whose combination allows us to create whatever we can imagine. In her playful scores, notes are not constrained to follow one another in standard ways; they can jump lines or make “quantum leaps”. These scores give us an idea of music as something both precise and unpredictable.

《仙儿念珠》,刘索拉,纸,98 x 84 cm,1998

Witch's Beads, Liu Sola, paper, 98 x 84 cm,1998

--变化中的传统形态

--The Changing Shape of Tradition

当我们想到传统时,我们必须克服一种双重偏见:或是认为传统已经过时,或是认为它已包含全部的答案。我们可能已经忘记了部分传统,或者我们无法觉察到它的相关性。例如,中国古代音乐中一个未被普遍承认的方面是,它使用了我们认为是现代发展的十二音音阶。这12个音可以排列在一个圆圈上,因此它顺时针的运动可以表示从阴到阳的运动,逆时针的运动则表示从阳到阴。形状可以改变:作为结构的圆可以转变成双三角形。在一种情况下,底部(阳)在上面,变窄到顶点(阴);在另一种情况下,顶点在上面,并向底部变宽。刚刚描述的是索拉的一个乐谱的形状。借鉴传统不应该被视为对关注当代的对立;而是说,它涉及到重新审视被忽视的事物,并将其置于当代经验的语境之中。

《自在魂》,刘索拉,2009

The Afterlife of Li Jiantong, Liu Sola, 2009

When we think of tradition, we have to overcome a double prejudice: the view that tradition is outdated or that it has all the answers. There may be parts of tradition we have forgotten or whose relevance we are not able to discern. For example, one aspect of ancient Chinese music that is not generally acknowledged is that it uses a 12-tone scale which we think of as a modern development. The 12 tones can be arranged on a circle, so that a clockwise movement can indicate a movement from Yin to Yang, and a counter-clockwise movement, from Yang to Yin. The forms can change: the circle as structure can transform into a double triangle. In one, the base (Yang) is on top, and it narrows to an apex (Yin); in the other, the apex is on top and it widens towards its base. What has just been described is the shape of one of Sola’s scores. Drawing on tradition should not be seen as antithetical to a concern with the contemporary; rather it involves looking again at the overlooked and and placing them in the context of contemporary experience.

阿克巴·阿巴斯

Ackbar Abbas

《中国拼贴》,作曲 | 刘索拉,制作 | Bill Laswell,日本Avan 唱片公司,录音艺术家 | 刘索拉、吴蛮,1996

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享