陳界仁

Lin & Lin Gallery is presenting Her and Her Children—Introduction and Prologue, a solo exhibition by Chen Chieh-Jen, from September 16 to November 25, 2023. The exhibition will include the artist’s most recent video works In a World Losing Multiple Worlds I (2022) and Worn Away (2022 – 2023), as well as still photography and sketches, from the series Her and Her Children.

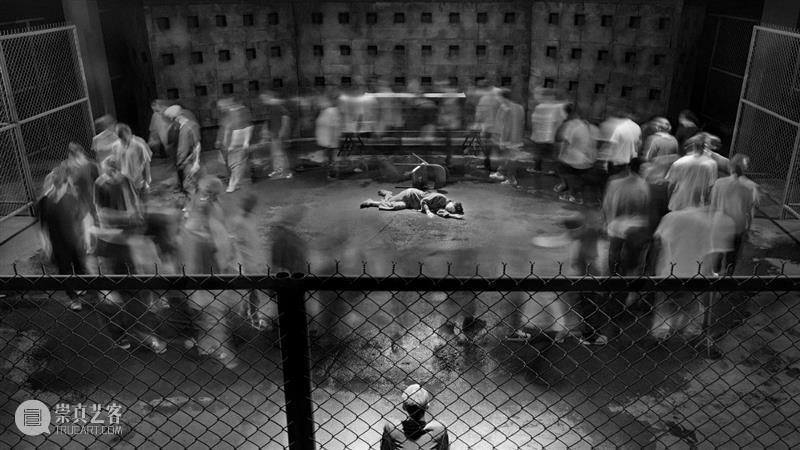

Worn Away

《風摧肉身》 Worn Away

2022-2023, 黑白.有聲.69分30 秒.16:9.單頻道錄影.循環放映

Black and White, Sound, 69’30”, 16:9, Single Channel Video, Continuous Loop Projection

維也納分離宮展場照 Installation view, Secession, 2023

攝影師 Photo: Oliver Ottenschläger

創作緣由與工作方法

Motivation and Methodology

陳界仁

Chen Chieh-jen

我不知道科技奇點何時才算真正到來?但我們已實質生活在由跨國金融資本集團、軍工複合體、數位與生物科技巨頭等公司王國所共構的帝國中,同時帝國通過掌控全球互聯網系統,操控絕大多數人感知世界的途徑與管道,並在全域式操控技術的誘導下,將人們引入各種迷向空間內,而異議之聲則幾乎被驅逐至可被觸及的範圍外。

此刻,我們已越來越難判斷無數事件的真偽,這不禁讓我想到東西方對於何謂幻象的不同觀點與指涉,為了便於表述與區分,我以梵文的幻相(māyā)這一詞彙,表述東方觀點(主要為佛教)下所說的「幻象」。

It is impossible to predict at exactly what point the technological singularity will emerge, but in substance, we are already living in an empire constructed by a corporatocracy of transnational financial conglomerates, military industrial complexes, and digital and biotech giants. Through the global Internet, the empire manipulates how the vast majority perceives the world, and the common people, influenced by pervasive control technology, are led into various spaces of disorientation while almost all dissenting voices are marginalized.

At this juncture, the authenticity of countless events has become increasingly difficult to determine. This leads one to consider the difference between Western and Eastern perspectives on illusion. To facilitate the distinction and for ease of expression, the Sanskrit term māyā can be used for the Eastern perspective, which is primarily from Buddhism.

《風摧肉身 – 等待通知》 Worn Away — Waiting for Notification

黑白照片.典藏級相紙 b/w photo, archival quality photo paper

2022-2023, 85x150 cm

在柏拉圖著名的洞穴寓言中,幻象與真實是處於絕對對立的二元關係,但佛教談論的幻相,指的是宇宙中的所有事物,都處於不斷流變的狀態,沒有什麼事物具有絕對的本質,也沒有什麼事物能永遠保持不變——而這才是所有事物,為何會匯聚、形成、存在、衰敗與消逝的原因。佛陀之所以提出此論點,其中一個核心關懷,即是為了打破婆羅門階級通過龐大的神話敘事所建構的種姓制度。換言之,佛陀藉由指出沒有什麼事物具有絕對不變的本質,因此所有的眾生(包含所有物種)都是平等的,更不存在血緣、種族與文化上的貴賤之分。

In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the distinction between mere shadows and reality is absolute, and these two elements, illusion and reality, are set in opposition. In Buddhism, however, māyā or illusory appearances, refers to the fact that everything in the universe is in a state of constant flux, that nothing possesses an absolute essence, and that nothing is forever immutable. This applies to each and every thing and explains the basis for matter coming together to form objects, which exist for a time and then decay and disappear. A core concern of the Buddha in putting forward this thesis was to break the caste system constructed by the Brahmin class and supported by a sweeping mythological narrative. In other words, the Buddha, in pointing out that nothing has an absolute and unchanging essence, made it clear that all living beings, including all species, are equal, and no distinctions can be made concerning blood, race, or culture.

但當前的人類社會,在帝國將新自由主義幻象成功植入絕大多數的國家與地區後,新種姓制度已然成形。以貧富懸殊問題為例,僅至2018年,全球前26名富豪所佔有之財富,已等於全球約一半(38億)較貧困人口所擁有的財產總和1,疫情期間,由於人們不得不深度依賴網路,更加劇貧富差距的擴大2;同時在加速主義所製造的巨大生存壓力下,根據世衛組織報告表示,全球於疫情期間的第一年,患有心理疾病者的發病率上升了25%以上,使得患有心理疾病的人數增至近 10 億人3。

Currently, however, following the empire’s successful establishment of illusory neoliberalism in most countries and regions, new caste systems have already taken shape in many societies. Take the income disparity between the rich and poor for example: As of 2018, the wealth owned by the world’s top twenty-six richest individuals is equal to the wealth owned by the poorer half of the global population, or 3.8 billion people.1 During the pandemic, heavy reliance on the Internet exacerbated this wealth gap2, and simultaneously, under the enormous pressures caused by accelerationism and the subsequent fight for survival, the incidence of mental illness increased by twenty-five percent in 2020 alone according to a report published by the World Health Organization, thereby increasing the number of people suffering from mental illness to nearly one billion.3

《風摧肉身 – 是諸眾等》 Worn Away — All Beings

黑白照片.典藏級相紙 b/w photo, archival quality photo paper

2022-2023, 85x150 cm

此刻,重新招喚佛教的幻相觀,是可以作為解構新幻象的方法之一,亦即,以追求眾生平等的未來觀,解構帝國將新種姓制度自然化的未來觀。或者說,就文化與藝術生產而言,關鍵不在於其內容為真實或虛構等問題,而在於無論採取何種表現形式,其是否是在新種姓制度下,指出通向平等社會的各種途徑。

The creation of this new caste system must involve an enormous transformation process, the core of which is the non-stop generation of new illusions that lure each new generation into the space of disorientation established by the empire.

Invoking the Buddhist concept of māyā in this era serves as a means of deconstructing new illusions, that is, it offers an alternative future perspective that posits the equality of all beings while deconstructing the empire’s view normalizing the new caste system. This can also be applied to cultural and artistic production, which has the potential to point out various paths to equality, regardless of what form the production takes and whether its content is based in realism or fiction.

變文產生於中國唐代(618─907),原為佛教由印度傳入中國時,為方便傳教,而借由「俗講僧」以講唱方式,將深奧的佛理,轉化成一般人易於理解的話語與故事,俗講的內容被書寫成文字,即為變文。如果說,歷史上的俗講僧既是解經、轉譯與改寫者,同時也是創造對話場域的表演藝術家。那麼,若將此具有多重身分的「俗講僧」之意義,置於當代社會的現實內,進行再想像與再詮釋,或許,當代意義的「俗講僧」,已不再只是解釋、轉譯、改寫已被完整化的正典理論者,而更像是對帝國複雜的新治理工程,進行解魅與解幻的解構者,以及激發諸眾提出不同未來觀的觸發者。

Bianwen is a Tang Dynasty (618—907) literary form that evolved along with the spread of Buddhism from India to China. To facilitate understanding of esoteric sutras, Sujiang Monks transformed them into vernacular stories and then performed the stories for the common people. Transcriptions of these performances are called bianwen. By interpreting, translating, and rewriting scripture, Sujiang Monks were similar to modern-day performance artists who construct discursive fields. But to place these historical figures in contemporary society would be to reimagine or redefine their significance, as they would no longer be interpreters, translators, and rewriters of canonical theory, but rather more like deconstructionists chasing away the sorcery and illusions employed in the complex new control project undertaken by the empire, or like those who prompt everyone to imagine a different future.

《風摧肉身 – 闔上雙眼》 Worn Away — Closing the Eyes

黑白照片.典藏級相紙 b/w photo, archival quality photo paper

2022-2023, 85x150 cm

「落地掃」的起源不詳。大致為農業時代,農民於農閒時,在村莊的空地或大樹下,就地打掃出一小塊地方,演出地方戲曲給同村的農民看,這種農民自我組織與自娛自樂的文化生產方式,被泛稱為「落地掃」。對我而言,「落地掃」還可以帶給我們的啓發是──當農民在進行自我組織與自娛自樂的業餘演出時,他們的身分既是農民,也是戲曲中某個跨性別的角色,或者是一個神話人物。而那個演出的當下,不但是藝術發生的時刻,更是一個農民不再局限於農民身分,而是匯集了農民、演員(藝術家)與神話人物等多重身分的人。同時,在中國農民起義的歷史裏,這類地方自我組織的戲曲表演,也常成為農民起義時的串連媒介。

The origins of lo-deh sao are unclear, but it most likely began in the pre-industrial era, when farmers would sweep clean a spot in the village, perhaps under a tree, and perform simple operas during the fallow season. This form of cultural production organized for the amusement of the villagers was called lo-deh sao, meaning “to sweep the ground.” Lo-deh sao still has the power to inspire us today. By organizing this entertainment, farmers also became amateur performers taking on the identities of mythical figures or portraying characters of the opposite sex. Not only were they creating art during these performances, but more importantly, they were afforded an opportunity to transcend their identities; it might be said that the multiple identities of farmer, performer (artist), and mythical figure converged in one individual. Furthermore, in China’s history, these local self-organized theater performances often became vehicles for peasant uprisings.

在台灣被日本殖民時期(1895─1945),由蔣渭水創立的台灣文化協會(1921─1927),於1926年成立專門放映默片的電影巡迴放映隊「美台團 」(1926─1927)。

日本殖民台灣時期,屬於台灣人經營的戲院內,通常會有日本警察與消防隊員坐鎮於觀眾席的最後一排,借以監控、防止台籍電影解說員,借機鼓吹反殖民意識。而屬於台灣文化協會電影迴放映隊的電影解說員,則會利用只有台灣觀眾才能聽懂的方言、俚語與諺語,將原本不具反殖民色彩的默片,「曲解」成具反殖民意涵的情節,而戲院內瞭解這些方言、俚語與諺語的觀眾,則會以大笑、鼓掌、吹口哨等聲音與肢體動作,回應台籍電影解說員對電影內容的「曲解」。

During the Japanese colonial period (1895—1945), Chiang Wei-shui established the Taiwanese Cultural Association, which operated from 1921 to 1927. The association formed a traveling team of projectionists and silent film narrators known as Bitai Thoan in 1926. At the time it was common for Japanese police officers or firefighters to be seated in the last row of theaters run by local Taiwanese. Their purpose was to monitor film narrators and prevent them from advancing anti-colonial sentiment. These same narrators, however, would use Taiwanese dialect, slang, or sayings that only the local audience understood to deliberately create anti-colonial meaning in films where it had not existed before. The audience would laugh, applaud, cheer, and gesture when they heard these deliberately twisted interpretations.

《風摧肉身 – 敞開的迷宮》 Worn Away — A Wide Open Labyrinth

彩色照片.典藏級相紙 color photograph, archival quality photo paper

2022-2023, 100x150 cm

我舉這三個歷史案例的意思是——在當前帝國的全域式操控技術下,創作一件影像作品,也意謂我們應如當代的「俗講僧」一樣,首先應是一個對帝國所製造的各種幻象,進行解魅與解幻的解構者;而在生產影片的實踐過程中,應如生產當代「落地掃」般,將被自動化機器淘汰的失業勞工,被算法控制的各種約聘雇工,即將被AI取代的非物質勞動者,以及被排除至邊緣的異議者們,集結成一個既是搭建與創造場景/場域者,也是發出異議之聲的表演者,以及讓專業者與業餘者不斷相互滲透的影像生產團隊;而生產出來的影片,應往返於有聲與無聲之間,甚至可以是完全的默片,讓無論是參與演出者或具能動性的觀眾,都可在不完整的敘事中,加上自己的再想像與再敘事,如同在「美台團」的案例中——默片、電影解說員與觀眾之間的流變關係中,電影並不僅僅只是一個觀看物,同時也是創造事件與讓事件的意義能不斷擴延的觸媒。

The reason for focusing on these three examples is to suggest that, in this time when we are all subject to the empire’s pervasive control technology, contemporary video artists can first of all follow the example of the Sujiang Monks and deconstruct the sorcery and illusions that the empire employs. The practice of film production can also be like organizing lo-deh sao; laborers eliminated by automation, temporary contract workers controlled by algorithms, immaterial labor that is being replaced by AI, and those with dissenting opinions who have been forced to the margins can all gather together and construct a platform where they can create scenes, become performers, and make their voices heard. In this way, professional and amateur members of the video production team can continually interact. The videos they produce should fall somewhere between being silent and having sound, or may even be completely silent to leave room for both participating performers and active audience members to add their own imaginations and narrations. Like the case of Bitai Thoan, where fluid relationships between silent films, narrators, and the audience were found, these contemporary videos would serve not merely as objects for observation, but also as catalysts prompting events that continually expand their significance.

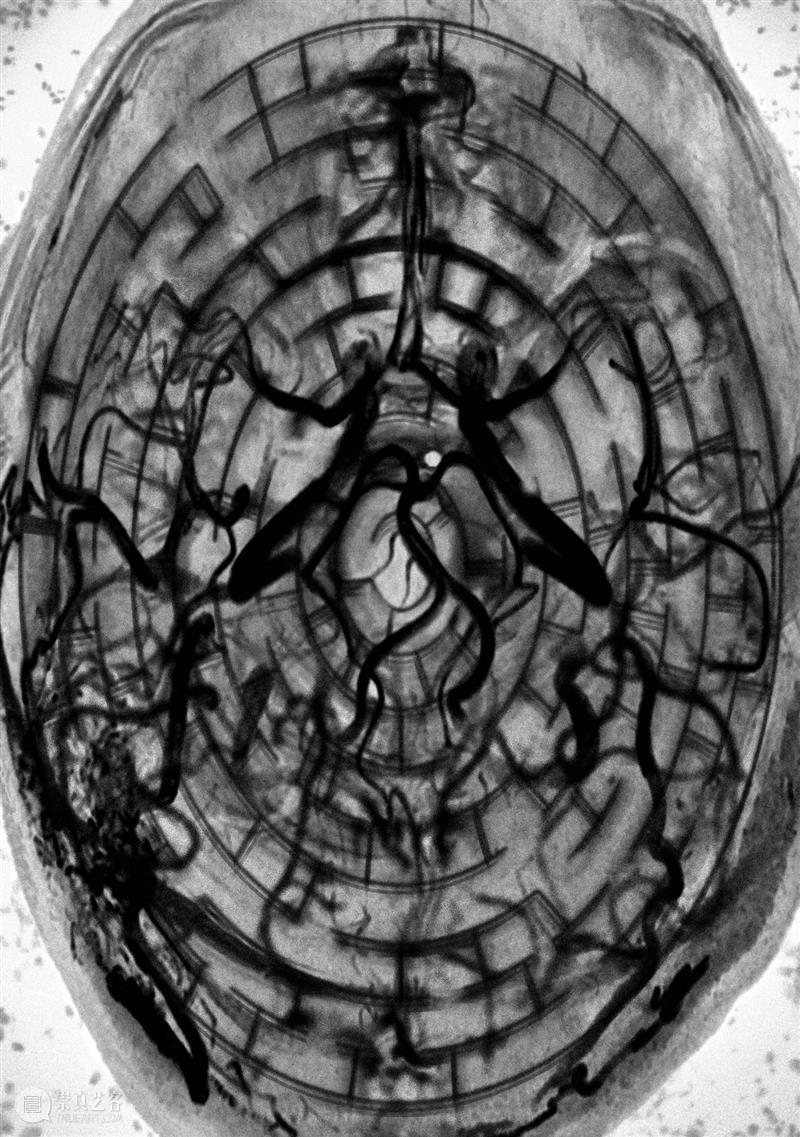

《風摧肉身 – 概念發展圖 – 1》

石墨、碳粉轉數字合成.典藏級水彩紙

2022, 155x109 cm

【註1】: 參閱 See:

https://oi-files-d8-prod.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2019-12/191219_Oxfam_Annual_Report_2018-19.pdf

【註2】: 參閱 See:https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621477/bp-survival-of-the-richest-160123-en.pdf

【註3】: 參閱 See:file:///Users/apple/Downloads/9789240049338-eng.pdf

【註4】:「謠言」在中文的原初意涵是「民間流傳評議時政的歌謠或諺語」,因此,「謠言」的意思應更接近──人民通過詩性的語言、歌謠和虛構的敘事策略,對掌握統治機器的權力者與具體的社會問題,進行介入與干預,並藉此生產出不同於統治者觀點的各種異議觀點與異議想像。

TheChinese term yaoyan originally referred to sayings or rhymes circulating in society that were critical of the government. Yaoyan was a strategy relying on poetic language, songs, and fabricated narratives to disrupt authorial mechanisms and comment on social issues. As a result, it produced points of view and social imaginaries that deviated from official narratives.

The first chapter of Her and Her Children, the film A Field of Non-Field, was completed in 2017.

Chen Chieh-jen, born in 1960 in Taoyuan, Taiwan, graduated from a vocational high school for the arts. He currently lives and works in Taipei, Taiwan. He has held solo exhibitions at the Vienna Secession; Art Sonje Center in Seoul; the Mudam Luxembourg; the Taipei Fine Arts Museum; Redcat art center in Los Angeles; the Museo Nacional Centro De Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid; the Asia Society in New York; and the Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume in Paris. Group exhibitions include: the Venice Biennial, São Paulo Biennial, Lyon Biennial, Liverpool Biennial, Gothenburg Biennial, Istanbul Biennial, Moscow Biennial, New Orleans Biennial, Sydney Biennial, Taipei Biennial, Gwangju Biennial, Shanghai Biennial, Shenzhen Sculpture Biennial, Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Guangzhou Triennial, Fukuoka Triennial, and the Asia Pacific Triennial. Chen has also participated in photography festivals in Arles, Spain and Lisbon; film programs of various international art institutes include: Tate Modern, Mori Art Museum, Centre Pompidou and dOCUMENTA 13. He was also the recipient of the Award of Art China—Artist of the Year in 2018, the Taiwan National Culture and Arts Foundation's National Award for Arts in 2009, and the Korean Gwangju Biennial Special Award in 2000.

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享