原载于《艺术史与艺术哲学集刊》第三辑

Paul Cézanne, Homme assis (Seated Man), 1905.Three Painters for Three Phenomenologists: Cézanne & Merleau- Ponty, Kandinsky & Henry, Tal Coat & MaldineyIf historically phenomenology was first constituted from a dialogue with sciences, in particular with mathematics and then logic, it was undoubtedly in its relation to art that this major philosophical current of the 20th century found its second wind. It was mainly with Heidegger that the question of art became an essential phenomenological question. In Heideggers Philosophie der Kunst, F.-W. von Herrmann clearly showed, despite what the title might suggest, that Heidegger never wanted to produce any theory of art or to aestheticize his own thought. For the phenomenologist, it was about opening up an original access to phenomenality itself through a meditation on the work of art.[1] It was in France that this dialogue between art and a phenomenological approach really flourished. Sartre’s role was undoubtedly important because of the proven influence that Husserl and Heidegger had on his early philosophy and, of course, of his own practice of literature. But before Sartre, there was Jean Wahl and his work on the relationship between Heideggerian thought and poetry. We must also mention the name of Jean Beaufret, personal friend of Heidegger and great connoisseur of art, in particular modern art, who encouraged the philosopher’s meeting with René Char and Georges Braque and enabled a whole generation of young phenomenologists like Jean-Luc Marion, Jean-Fran?ois Courtine, Fran?ois Fédier, Michel Deguy, Claude Ro?ls, Roger Munier and many others, to be made aware very early on about the challenges of this encounter between art and phenomenology.[2]Among these French phenomenologists who dedicated part of their works to the study of artistic and aesthetic phenomena, three names stand out in particular: Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Michel Henry and Henri Maldiney. We should for sure add to these names that of Jacques Derrida. However, unlike the latter, these three philosophers remained their lives attached to the phenomenological path and it is in this furrow that they deepened their dialogue with art, more particularly painting and more particularly still with the work of a painter. This specificity so allows us to better understand the originality of the phenomenological work on art as it took place in France and continues to take place, in the wake of what is called the French phenomenological tradition.

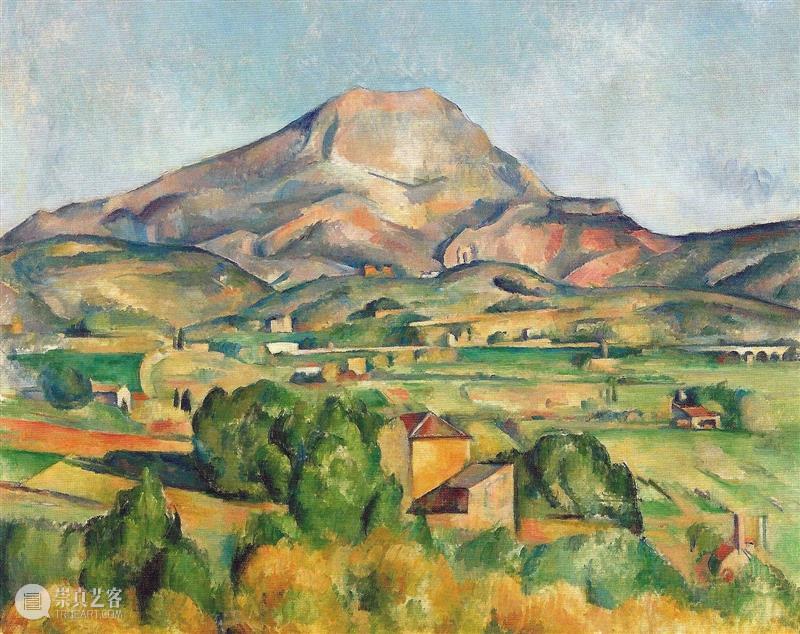

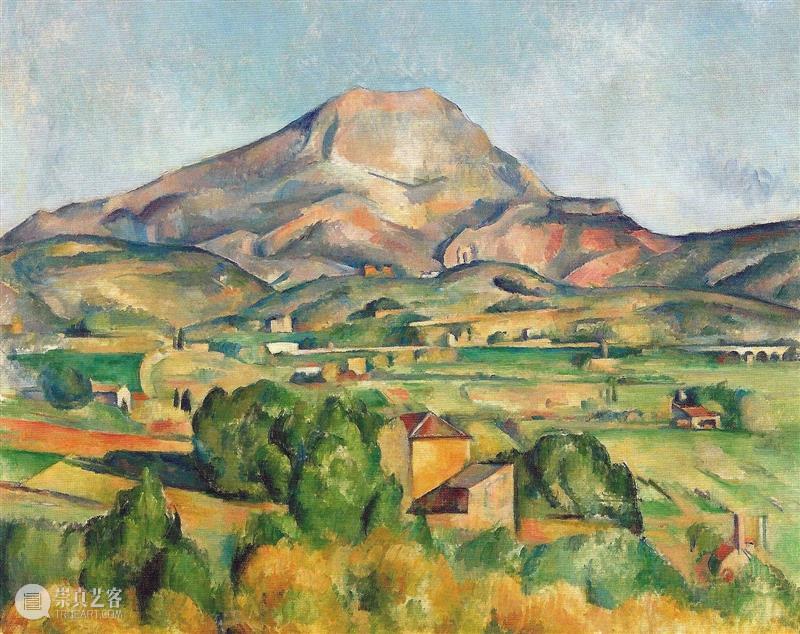

Paul Cézanne, Homme assis (Seated Man), 1905.Three Painters for Three Phenomenologists: Cézanne & Merleau- Ponty, Kandinsky & Henry, Tal Coat & MaldineyIf historically phenomenology was first constituted from a dialogue with sciences, in particular with mathematics and then logic, it was undoubtedly in its relation to art that this major philosophical current of the 20th century found its second wind. It was mainly with Heidegger that the question of art became an essential phenomenological question. In Heideggers Philosophie der Kunst, F.-W. von Herrmann clearly showed, despite what the title might suggest, that Heidegger never wanted to produce any theory of art or to aestheticize his own thought. For the phenomenologist, it was about opening up an original access to phenomenality itself through a meditation on the work of art.[1] It was in France that this dialogue between art and a phenomenological approach really flourished. Sartre’s role was undoubtedly important because of the proven influence that Husserl and Heidegger had on his early philosophy and, of course, of his own practice of literature. But before Sartre, there was Jean Wahl and his work on the relationship between Heideggerian thought and poetry. We must also mention the name of Jean Beaufret, personal friend of Heidegger and great connoisseur of art, in particular modern art, who encouraged the philosopher’s meeting with René Char and Georges Braque and enabled a whole generation of young phenomenologists like Jean-Luc Marion, Jean-Fran?ois Courtine, Fran?ois Fédier, Michel Deguy, Claude Ro?ls, Roger Munier and many others, to be made aware very early on about the challenges of this encounter between art and phenomenology.[2]Among these French phenomenologists who dedicated part of their works to the study of artistic and aesthetic phenomena, three names stand out in particular: Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Michel Henry and Henri Maldiney. We should for sure add to these names that of Jacques Derrida. However, unlike the latter, these three philosophers remained their lives attached to the phenomenological path and it is in this furrow that they deepened their dialogue with art, more particularly painting and more particularly still with the work of a painter. This specificity so allows us to better understand the originality of the phenomenological work on art as it took place in France and continues to take place, in the wake of what is called the French phenomenological tradition. Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire, 1885–1890.

Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire, 1885–1890.

Paul Cézanne according to Maurice Merleau-Ponty

The work as the figure of Paul Cézanne played an important role in the elaboration of the phenomenology Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology. Nothing in this sense is more significant than the philosopher wrote in the summer of 1960 his last text, Eye and Mind, in his house of the Tholonet located not far from Aix-en-Provence, in the countryside of Cézanne, very close to his favorite motives. In addition to this ultimate work, in which Cézanne is obviously everywhere present, Merleau-Ponty referred to the painter as early as The Structure of Behavior (1942), on the subject of the perception of faces.[3]From the Phenomenology of Perception (1945) the mentions of Cézanne increased in number (more than thirty) to the point of being able to consider these references no longer as simple illustrative mentions but as true examples serving to the elaboration of a radical phenomenology. It was in 1948, with the publication of Sense and Non- Sense, that the painter became a subject of study for the philosopher. The essay opens indeed with this famous first chapter entitled “The Cézanne’s Doubt.” We find the painter again in Signs (1960), in The Prose of the World (1964) and of course in this essay, which is as decisive as it is incomplete— just like many Cézanne’s paintings—The Visible and the Invisible (1964), where the reflection on the Cézanne’s work is articulated in the phenomenological revolution that Merleau-Ponty was preparing and that an untimely death prevented him from fully achieving.Cézanne therefore accompanied all of Merleau-Ponty’s work to the point that we can say that he was one of the essential companions on his philosophical and more particularly phenomenological path. In other words, one cannot and must not consider Cézanne as one reference among others that the philosopher would sprinkle over his works to give them a “cultural” flavour. Understanding Cézanne’s aesthetics participated for Merleau-Ponty in the development of his phenomenology. This is why the reference to Cézanne intervenes precisely in three interdependent fields that represent the triple core of Merleau-Pontian’s work: Perception, World and the Body. Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne, Mount Sainte-Victoire, 1885-95.? Learning to see: the lesson of Cézanne according to Merleau-PontyFollowing the call of Husserl to “go back to the things themselves,” Merleau-Ponty sought how to return to the truth of perception, in its very originality. How can we make such a comeback in a cultural context where, as Merleau-Ponty said, “we have unlearned how to see”[4]? Resorting to psychological description is not enough. It lacks the necessary radicalism due to its metaphysical dependence on empiricism and its objectivist orientation. It is thus towards the painter’s way of looking, towards its “pre-theoretical” dimension, that Merleau-Ponty turned his research on perceptual truth. But Why, among all the possible painters, did his choice fall—and insistently—on Cézanne? Because the “pre-theoretical” dimension of such a look isn’t without ambiguity.We generally understand this pre-theoretic dimension specific to the pictorial gaze from the gradual process of erasing the objective and drawn forms of classical representation in favour of an increasing valuation of solid areas of pure colour. Through this evolution, which is even a revolution, initiated by the Impressionists and radicalized by the Fauvists, painting frees itself from the domination of understanding imposed by the model of mimesis in order to give back to the sensible experience its primacy and thus make painting no longer a representation but a presentation of reality. However, the danger of such an approach is that it could, on the basis of a laudable intention to restore to the sensible impression its sovereign place, forget that the truth of the perception is located in the native unity of sensibility and sense[5] and operate a new divorce within the gaze. For the perceiving subject receives not only sensible impressions from the visible, but a configuration of being, a sense that makes a world. In other words, world and subject, visible and seer, sense (meaning) and sensibility arise for each other from an original co-belonging. Thus, any return to the truth of perception can only take place in the space of this primary unity that the only “seeing” painter knows how to achieve in a work. Now it is on this point that, according to Merleau-Ponty, Cézanne radically separated from Impressionism. He interpreted this separation as the sign of Cézanne’s fidelity to the truth of perception.[6] If indeed the purpose of Impressionism was to translate the very life of perception from its birth and movement, it achieved it by means of a decomposition of the coloured prism resulting in a dispersion of sensations. But, this fragmentation of the visible appearance as touches of juxtaposed colours, only the gaze of the spectator, at a certain distance, is then able to bring together afterwards. In itself, then, the Impressionism painting fails to capture the perceptual unity in the very unity of the pictorial space; it only gives the impression of it by means of an artifice of the gaze, which, if it is misplaced, dissolves it into pure multiplicity.With Cézanne, on the contrary, unity is given immediately through a communication of all parts of the painting and touches of colour. Real and living perception is no longer recomposed but given without mediation. How did he realize it? From what Cézanne himself called the “logic of organized sensations,” which reveals itself to him from very long contemplations of the “motiv.” Intelligence is no longer separated from sensibility. It emerges from the sensible itself and the painter’s first task is to see it at work and then to restore it as a work of painting. Cézanne’s painting therefore doesn’t work to reconcile the sensible and the intelligible. Its achievement takes place before their separation. By discovering the intelligence of sensibility, the law of harmony of the visible, the painter discovered in painting this truth of perception that Merleau-Ponty sought to render phenomenologically: namely that something is given to be seen in perception and that it is to this donation that the perceptual act responds. Perception doesn’t result from various sensible impressions first passively received and then recomposed into objectivities by understanding. Perception is the seeing openness to the visible, which comes to appearance in all its configuration, that is to say as a world not only sensible but also a world of things given together their set of relationships. This is what, as Merleau-Ponty said, a Cézanne’s painting manifests: “This relation of the visible to itself, which crosses me and constitutes me as a seer”[7]—or, as Cézanne himself wrote to émile Bernard: “Re-joining in painting the physiognomy of things and faces by restoring their sensible configuration.”[8] In other words: restoring the world.

Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne, Mount Sainte-Victoire, 1885-95.? Learning to see: the lesson of Cézanne according to Merleau-PontyFollowing the call of Husserl to “go back to the things themselves,” Merleau-Ponty sought how to return to the truth of perception, in its very originality. How can we make such a comeback in a cultural context where, as Merleau-Ponty said, “we have unlearned how to see”[4]? Resorting to psychological description is not enough. It lacks the necessary radicalism due to its metaphysical dependence on empiricism and its objectivist orientation. It is thus towards the painter’s way of looking, towards its “pre-theoretical” dimension, that Merleau-Ponty turned his research on perceptual truth. But Why, among all the possible painters, did his choice fall—and insistently—on Cézanne? Because the “pre-theoretical” dimension of such a look isn’t without ambiguity.We generally understand this pre-theoretic dimension specific to the pictorial gaze from the gradual process of erasing the objective and drawn forms of classical representation in favour of an increasing valuation of solid areas of pure colour. Through this evolution, which is even a revolution, initiated by the Impressionists and radicalized by the Fauvists, painting frees itself from the domination of understanding imposed by the model of mimesis in order to give back to the sensible experience its primacy and thus make painting no longer a representation but a presentation of reality. However, the danger of such an approach is that it could, on the basis of a laudable intention to restore to the sensible impression its sovereign place, forget that the truth of the perception is located in the native unity of sensibility and sense[5] and operate a new divorce within the gaze. For the perceiving subject receives not only sensible impressions from the visible, but a configuration of being, a sense that makes a world. In other words, world and subject, visible and seer, sense (meaning) and sensibility arise for each other from an original co-belonging. Thus, any return to the truth of perception can only take place in the space of this primary unity that the only “seeing” painter knows how to achieve in a work. Now it is on this point that, according to Merleau-Ponty, Cézanne radically separated from Impressionism. He interpreted this separation as the sign of Cézanne’s fidelity to the truth of perception.[6] If indeed the purpose of Impressionism was to translate the very life of perception from its birth and movement, it achieved it by means of a decomposition of the coloured prism resulting in a dispersion of sensations. But, this fragmentation of the visible appearance as touches of juxtaposed colours, only the gaze of the spectator, at a certain distance, is then able to bring together afterwards. In itself, then, the Impressionism painting fails to capture the perceptual unity in the very unity of the pictorial space; it only gives the impression of it by means of an artifice of the gaze, which, if it is misplaced, dissolves it into pure multiplicity.With Cézanne, on the contrary, unity is given immediately through a communication of all parts of the painting and touches of colour. Real and living perception is no longer recomposed but given without mediation. How did he realize it? From what Cézanne himself called the “logic of organized sensations,” which reveals itself to him from very long contemplations of the “motiv.” Intelligence is no longer separated from sensibility. It emerges from the sensible itself and the painter’s first task is to see it at work and then to restore it as a work of painting. Cézanne’s painting therefore doesn’t work to reconcile the sensible and the intelligible. Its achievement takes place before their separation. By discovering the intelligence of sensibility, the law of harmony of the visible, the painter discovered in painting this truth of perception that Merleau-Ponty sought to render phenomenologically: namely that something is given to be seen in perception and that it is to this donation that the perceptual act responds. Perception doesn’t result from various sensible impressions first passively received and then recomposed into objectivities by understanding. Perception is the seeing openness to the visible, which comes to appearance in all its configuration, that is to say as a world not only sensible but also a world of things given together their set of relationships. This is what, as Merleau-Ponty said, a Cézanne’s painting manifests: “This relation of the visible to itself, which crosses me and constitutes me as a seer”[7]—or, as Cézanne himself wrote to émile Bernard: “Re-joining in painting the physiognomy of things and faces by restoring their sensible configuration.”[8] In other words: restoring the world. Fig. 3 Paul Cézanne, Riverbanks, 1904-05.? Discovering the originality of the worldAmong the criticisms levelled at Husserl’s phenomenology, there is an important one which touches the world and its original mode of appearance. If Epoché, by suspending the thesis of the absolute existence of the world, shed lights on its essential relation to the subject (there is no world except in the horizon of a consciousness), the Reduction operated in the Cartesian Meditations made the obviousness of the world a “secondary” evidence, resulting in a way from the first obviousness of the transcendental subjectivity. But what is the basis for asserting that the obviousness of the world presupposes the evidence of the subject? As Jan Pato?ka wrote: “These two kinds of obviousness are obvious in the same degree.”[9] World and subject are necessarily co-appearing; just as the visible and the seer are. Now where is the space of this double evidence of the world and of the located Self? “In perception,” maintained Merleau-Ponty: World and subject co-appear in perception.[10]It is this co-birth of world and subject that Merleau-Ponty saw at work in Cézanne’s paintings. He saw in it the truth of the world as truth of perception—this “truth in painting” as claimed by Cézanne. This essential unity is no longer based on the impressionist effect. Cézanne rendered it fully, in the sense that the painting fully expresses the integrity of the visible—which requires the painter to become “an upstanding seer,” i.e., to know how “to stand on the motif,” as Cézanne said. It is this concern for complete restitution that gives this Cézanne’s works this sense of primitive unity, in which the communication of everything with everything is visible. “If the painter wants to express the world, the arrangement of the colours must carry within it this indivisible Whole,” wrote Merleau-Ponty.[11]Or as Cézanne said: “Painting until the blue scent of pines and the distant marble fragrance of Sainte-Victoire.”[12]

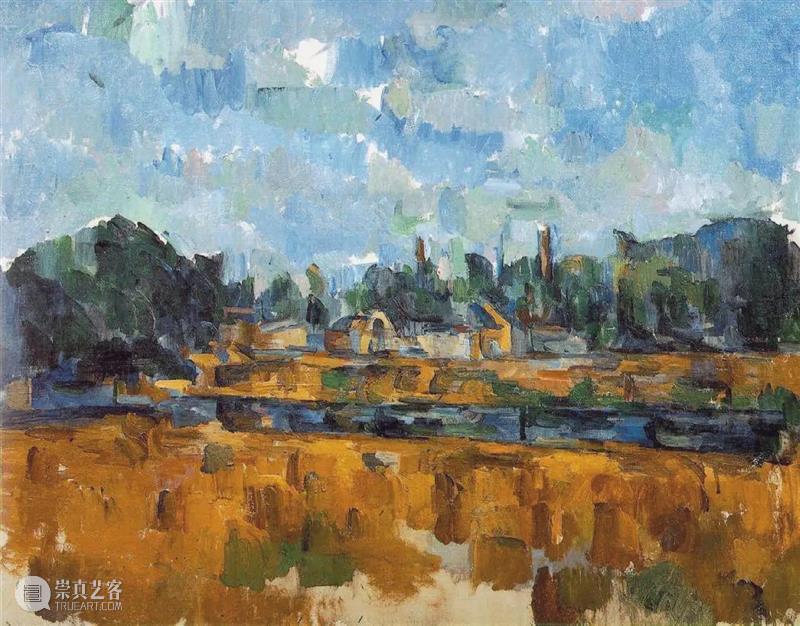

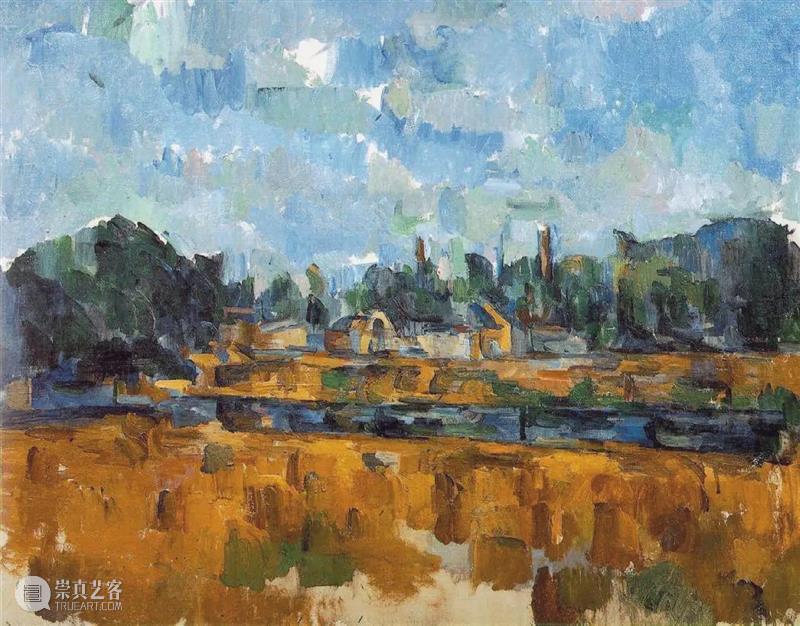

Fig. 3 Paul Cézanne, Riverbanks, 1904-05.? Discovering the originality of the worldAmong the criticisms levelled at Husserl’s phenomenology, there is an important one which touches the world and its original mode of appearance. If Epoché, by suspending the thesis of the absolute existence of the world, shed lights on its essential relation to the subject (there is no world except in the horizon of a consciousness), the Reduction operated in the Cartesian Meditations made the obviousness of the world a “secondary” evidence, resulting in a way from the first obviousness of the transcendental subjectivity. But what is the basis for asserting that the obviousness of the world presupposes the evidence of the subject? As Jan Pato?ka wrote: “These two kinds of obviousness are obvious in the same degree.”[9] World and subject are necessarily co-appearing; just as the visible and the seer are. Now where is the space of this double evidence of the world and of the located Self? “In perception,” maintained Merleau-Ponty: World and subject co-appear in perception.[10]It is this co-birth of world and subject that Merleau-Ponty saw at work in Cézanne’s paintings. He saw in it the truth of the world as truth of perception—this “truth in painting” as claimed by Cézanne. This essential unity is no longer based on the impressionist effect. Cézanne rendered it fully, in the sense that the painting fully expresses the integrity of the visible—which requires the painter to become “an upstanding seer,” i.e., to know how “to stand on the motif,” as Cézanne said. It is this concern for complete restitution that gives this Cézanne’s works this sense of primitive unity, in which the communication of everything with everything is visible. “If the painter wants to express the world, the arrangement of the colours must carry within it this indivisible Whole,” wrote Merleau-Ponty.[11]Or as Cézanne said: “Painting until the blue scent of pines and the distant marble fragrance of Sainte-Victoire.”[12] Fig. 4 Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne en robe rouge (Madame Cezanne in a Red Dress), 1890.However, warned Merleau-Ponty, if the world and the subject or the visible and the seer co-appear in perception, they nevertheless don’t coincide.[13]Therefore, expressing what exists can only be an infinite task. Faithful on this point to the teaching of Husserl, Merleau-Ponty insists a lot on the fact that the world is not given to us in the mode of an object but always in sketches: “The quality is the outline of a thing and thing the outline of the world.”[14] The world presents itself in a “sketch of being, which is reflected in the concordances of my experience.”[15]However, this is not a lacuna, for the unity of the world is an open unity, which corresponds in perception to the open and indefinite unity of subjectivity. This is why, in Cézanne’s Doubt, Merleau-Ponty was sorry that the painter saw in the incompletion of a large number of his paintings a sign of his own failure.[16] On the contrary, Merleau-Ponty saw in this incompleteness the most faithful testimony to this gap between the seer and the visible, which is also a part of world true experience. The blanks left by Cézanne in his paintings are not lacks but spaces left open by the play of the “seer/visible” or “subject/world” relationship. The world is therefore not lacking in these Cézanne’s blanks. It shows itself just as much as in the painted parts and with an obviousness that will never reach any saturation.

Fig. 4 Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne en robe rouge (Madame Cezanne in a Red Dress), 1890.However, warned Merleau-Ponty, if the world and the subject or the visible and the seer co-appear in perception, they nevertheless don’t coincide.[13]Therefore, expressing what exists can only be an infinite task. Faithful on this point to the teaching of Husserl, Merleau-Ponty insists a lot on the fact that the world is not given to us in the mode of an object but always in sketches: “The quality is the outline of a thing and thing the outline of the world.”[14] The world presents itself in a “sketch of being, which is reflected in the concordances of my experience.”[15]However, this is not a lacuna, for the unity of the world is an open unity, which corresponds in perception to the open and indefinite unity of subjectivity. This is why, in Cézanne’s Doubt, Merleau-Ponty was sorry that the painter saw in the incompletion of a large number of his paintings a sign of his own failure.[16] On the contrary, Merleau-Ponty saw in this incompleteness the most faithful testimony to this gap between the seer and the visible, which is also a part of world true experience. The blanks left by Cézanne in his paintings are not lacks but spaces left open by the play of the “seer/visible” or “subject/world” relationship. The world is therefore not lacking in these Cézanne’s blanks. It shows itself just as much as in the painted parts and with an obviousness that will never reach any saturation. Fig. 5 Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne au fauteuil jaune (Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Armchair), 1895.This intimate relationship that Cézanne’s painting maintains with the phenomenological truth of the world cannot be reduced to landscapes. The “mystery of the expression of the world”[17]is just as present in his portraits. Merleau-Ponty thus devoted admirable pages[18]to the Portrait of Vallier (1906), showing how it too “made a world.” The philosopher saw in it the realization of man-world unity. Now in this portrait, or in those of The Seated Man (1905), of Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1890) or of the one in the Yellow Armchair (1895), as in the landscapes of maturity, Merleau-Ponty noticed how the harmonic system of touches, while bringing back the painting on the surface, also creates a profundity that doesn’t come from the geometrical artifice of perspective. It is in chapter IV of Eye and Mind (L’?il et l’esprit) that he developed this theme of “Cézanian profundity.” It is no longer a simple space or a dimension of space but the realization into an artwork of phenomenality itself, i.e., the way in which the world appears to us:It is the canvas-support, which has two dimensions, the painting contemplated has an infinity of them. And the perception of the world too. There is a questioning of the look at the thing. It asks it how it is made “thing” and the world “world.”[19]? Painter’s body and body of paintingThis appearing of the world in its own profundity, based on the Cézanne art of portraiture, opens up the last essential point of the dialogue that Merleau-Ponty maintained with Cézanne’s painting: the dimension of the body. We should also say the dimensions of the body since it concerns together the body in painting, the body of the painter and the seeing body. As written in the Phenomenology of Perception, in the chapter dedicated to the synthesis of the own body: “To be a body is to be tied to a certain world and our body isn’t primarily in space: it is to the space.”[20]Given the intimate relationship of Cézanne’s painting to the world and his intense meditation on pictorial space, one can expect that Merleau-Ponty, for whom the problem of the phenomenological status of the body arose with intensity, also looked for solutions in Cézanne’s work. As he wrote in Eye and Mind: “The painter brings his body.”[21] But how? Through his style or through what we call “expression.” Any style or any true expression comes from the body: “All human use of the body is already primordial expression.”[22] Understanding the style of a painter therefore comes down to seizing this primordial expression, in which the body is originally invested. However, is invested in painting by the gaze first and then by the gesture. It is when the gaze and the gesture are in full continuity in the same relationship to the world and to the self that a style may appear. “This is how, by offering his body to the world, the painter changes the world into painting.”[23]This communion of seeing and doing therefore characterizes the expressiveness of the pictorial gesture, which is nothing other than the expressiveness of the body in general and “the emblem of a way of inhabiting the world”[24] so that a world is to be painted in the same fundamental way as a world is to be inhabited. It is this existential fact that Merleau-Ponty discovered in the Cézanne style, where the gaze becomes intimately touch and where the vibratory harmony of the touches becomes a world in painting.

Fig. 5 Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne au fauteuil jaune (Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Armchair), 1895.This intimate relationship that Cézanne’s painting maintains with the phenomenological truth of the world cannot be reduced to landscapes. The “mystery of the expression of the world”[17]is just as present in his portraits. Merleau-Ponty thus devoted admirable pages[18]to the Portrait of Vallier (1906), showing how it too “made a world.” The philosopher saw in it the realization of man-world unity. Now in this portrait, or in those of The Seated Man (1905), of Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1890) or of the one in the Yellow Armchair (1895), as in the landscapes of maturity, Merleau-Ponty noticed how the harmonic system of touches, while bringing back the painting on the surface, also creates a profundity that doesn’t come from the geometrical artifice of perspective. It is in chapter IV of Eye and Mind (L’?il et l’esprit) that he developed this theme of “Cézanian profundity.” It is no longer a simple space or a dimension of space but the realization into an artwork of phenomenality itself, i.e., the way in which the world appears to us:It is the canvas-support, which has two dimensions, the painting contemplated has an infinity of them. And the perception of the world too. There is a questioning of the look at the thing. It asks it how it is made “thing” and the world “world.”[19]? Painter’s body and body of paintingThis appearing of the world in its own profundity, based on the Cézanne art of portraiture, opens up the last essential point of the dialogue that Merleau-Ponty maintained with Cézanne’s painting: the dimension of the body. We should also say the dimensions of the body since it concerns together the body in painting, the body of the painter and the seeing body. As written in the Phenomenology of Perception, in the chapter dedicated to the synthesis of the own body: “To be a body is to be tied to a certain world and our body isn’t primarily in space: it is to the space.”[20]Given the intimate relationship of Cézanne’s painting to the world and his intense meditation on pictorial space, one can expect that Merleau-Ponty, for whom the problem of the phenomenological status of the body arose with intensity, also looked for solutions in Cézanne’s work. As he wrote in Eye and Mind: “The painter brings his body.”[21] But how? Through his style or through what we call “expression.” Any style or any true expression comes from the body: “All human use of the body is already primordial expression.”[22] Understanding the style of a painter therefore comes down to seizing this primordial expression, in which the body is originally invested. However, is invested in painting by the gaze first and then by the gesture. It is when the gaze and the gesture are in full continuity in the same relationship to the world and to the self that a style may appear. “This is how, by offering his body to the world, the painter changes the world into painting.”[23]This communion of seeing and doing therefore characterizes the expressiveness of the pictorial gesture, which is nothing other than the expressiveness of the body in general and “the emblem of a way of inhabiting the world”[24] so that a world is to be painted in the same fundamental way as a world is to be inhabited. It is this existential fact that Merleau-Ponty discovered in the Cézanne style, where the gaze becomes intimately touch and where the vibratory harmony of the touches becomes a world in painting.* Renmin University of China, email: alexis_lavis@yahoo.fr

[1]F.-W. von Herrmann, Heideggers Philosophie der Kunst(Frankfurt: Klostermann, 1994), 2–3.

[2]See Dominique Janicaud, Heidegger in France, trans. Fran?ois Raffoul & David Pettigrew (Indiana University Press, 2015).

[3]Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Structure du comportement (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1967), 220.

[4]Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception(Paris: NRF, Gallimard, 1945), 282.

[5]Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception, 171–172.

[6]Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Sens et non-sens(Paris: Nagel, 1966), 18–19.

[7]Maurice Merleau-Ponty, L’?il et l’esprit(Paris: Gallimard, 1964), 183.

[8]Paul Cézanne, Correspondance(Paris: Grasset, 1978), 315.

[9]Jan Pato?ka, Qu’est-ce que la phénoménologie?, trans. E. Abrams (Grenoble: Jérome Millon, 1988), 177.

[10]Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception, 531.

[11]Merleau-Ponty, Sens et non-sens, 22.

[12]Cézanne, Correspondance, 110.

[13]Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception, 376.

[14] Ibid., 465.

[15]Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception, 465.

[16]Merleau-Ponty, Sens et non-sens, 33.

[17]Merleau-Ponty, Sens et non-sens, 27.

[18]Merleau-Ponty, L’?il et l’esprit, 65–69.

[19]Merleau-Ponty, Notes de cours 1959–1961(Paris: Gallimard, 1996), 170.

[20]Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception, 173.

[21]Merleau-Ponty, L’?il et l’esprit, 31.

[22]Merleau-Ponty, Signes(Paris: NRF, Gallimard, 1960), 84.

[23]Merleau-Ponty, L’?il et l’esprit, 16.

[24]Merleau-Ponty, Signes, 68.

作者简介:Alexis LAVIS,中国人民大学哲学院副教授、杰出青年学者。国际哲学公学院(CIPh)项目主任(任期2022-2028)、法国国家科学中心(CNRS)胡塞尔文献室研究员、法国Le Cerf出版社哲学部"Asian Studies"主编、Le Monde·Religions《世界报·宗教》杂志编委、鲁昂大学哲学博士,professeur agrégé de philosophie,从事现象学和比较哲学(儒家、道家、印度佛教)研究,专精法语、英语、梵语、德语、古希腊语、拉丁语,熟练使用古汉语、意大利语。曾在法国鲁昂大学哲学院、巴黎政治学院任职。

Paul Cézanne, Homme assis (Seated Man), 1905.

Paul Cézanne, Homme assis (Seated Man), 1905. Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire, 1885–1890.

Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne, Montagne Sainte-Victoire, 1885–1890.  Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne, Mount Sainte-Victoire, 1885-95.

Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne, Mount Sainte-Victoire, 1885-95. Fig. 3 Paul Cézanne, Riverbanks, 1904-05.

Fig. 3 Paul Cézanne, Riverbanks, 1904-05. Fig. 4 Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne en robe rouge (Madame Cezanne in a Red Dress), 1890.

Fig. 4 Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne en robe rouge (Madame Cezanne in a Red Dress), 1890. Fig. 5 Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne au fauteuil jaune (Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Armchair), 1895.

Fig. 5 Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne au fauteuil jaune (Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Armchair), 1895.

分享

分享