Kandinsky Vassily Rotterdam Sun

Three Painters for Three Phenomenologists: Cézanne & Merleau- Ponty, Kandinsky & Henry, Tal Coat & Maldiney

Alexis Lavis*

Alexis Lavis|Three Painters for Three Phenomenologists(Part 1)

Vassily Kandinsky according to Michel Henry

As one of the great representatives of the French Phenomenology, Michel Henry is particularly recognized for his work devoted to the affective and self-affected life. However, since the publication in 2003 of the third volume of his posthumous works[1], gathering numerous of writings on art, we can take even more measure of the depth of his aesthetic reflection. However, it didn’t take until that date to get a glimpse of it. In 1988, Michel Henry published an entire and important book devoted to Vassily Kandinsky, Seeing Invisible: on Kandinsky (Voir l’invisible, sur Kandinsky). Here again, to the same extent as Merleau-Ponty with Cézanne and perhaps even more so, Henry established a dialogue between his own phenomenological perspective and the works and writings of Kandinsky. If one had to summarize the central idea animating such a dialogue, we could say that Henry proposes, starting from Kandinsky, a theory of Abstraction as art of pure Interiority.Abstraction radicalizes this movement initiated by the Impressionists consisting, as we have seen, in dissolving objectively graspable things in a flow of colours. More than a landscape, a Monet’s painting presents an atmosphere, a climate or an ambience. Painting, by abandoning objectivity, produces a modification of the gaze by turning it from the outside to the inside. What painting gives to see are no longer things but their sensible presence, that is to say their inner appearing. Through such a movement of subjectivation of the gaze, colours and shapes take on their own aesthetic value because they are freed from their link to the logic of objective representation. It is precisely this double movement of liberation of colour and of interiorization of the gaze, which is felt in its own sensibility in contact with the artwork, that abstraction would have radicalized, according to Kandinsky and Henry.Such a movement is reminiscent of that made by Husserl in §§ 85 and 86 of the Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology I, as Michel Henry then reminded us. If consciousness of objects is entirely determined by intentionality, the entirety of lived experience isn’t limited to the exteriorizing horizon of the noetic-noematic relationship. There is a layer (Schichten) of the pre-intentional and therefore pre-objective experience made up of the free play of pure sensible impressions, the hyle. Phenomenology has therefore to consider not only the appearing of things but also the appearing of the pure sensible, that is to say what is not yet determined as a set of objective qualities. Husserl thus announced that he wanted to establish an “Hyletics”—i.e., a phenomenological aesthetic of pure subjectivity—as an “autonomous discipline.”[2]This was undoubtedly a response to the transcendental aesthetic of Kant, whom Husserl criticized in 1935 for its “weakness.”[3]And indeed, it must be recognized that if Kant was able to distinguish in the field of sensible experience its double affective (hyle) and formal dimension, the philosopher dealt only with forms and almost not with affection. We can thus say of Kant’s transcendental aesthetics that it is certainly transcendental but very few aesthetical. Unfortunately, this project of constituting a true Hyletics wasn’t carried out by Husserl. It was to this task that Michel Henry devoted himself in his own way through his material phenomenology[4] and his phenomenology of life. However, if this Hyletics couldn’t be achieved during Husserl’s time, Henry sees it carried out in painting through the work of Kandinsky. However, this should be done justice to Goethe who, in his remarkable Theory of Colours (part VI), attempted such an approach through his study of the “sensual-moral influence of colors” (sinnlich-sittliche Wirkung der Farben)[5] . Hermitage ~ part 14 – Kandinsky, Vasily - Composition VI

Hermitage ~ part 14 – Kandinsky, Vasily - Composition VI

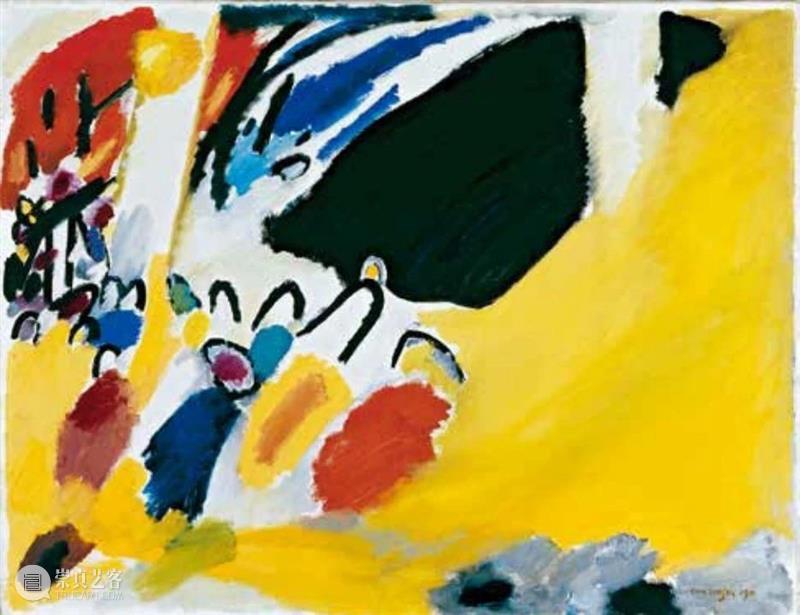

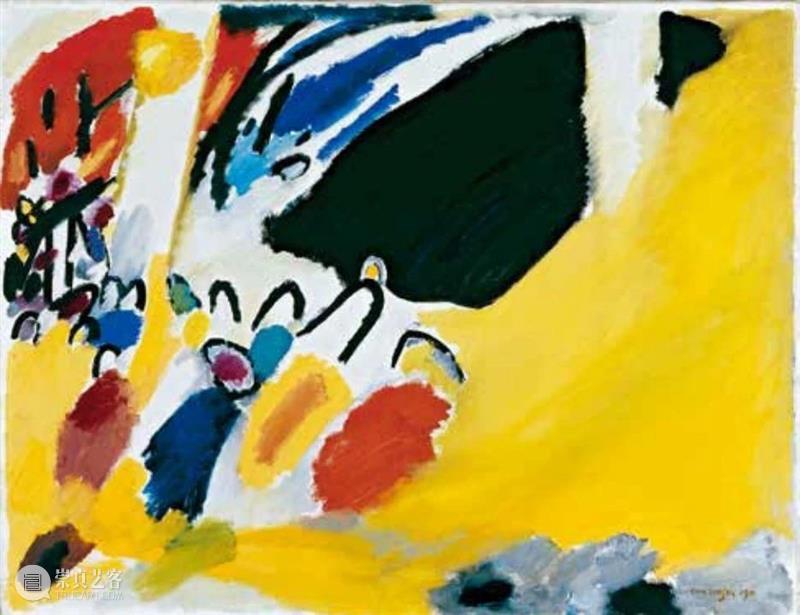

Kandinsky’s painting radicalized the tendency towards the subjectification of visual experience initiated by the Impressionists and especially by the Fauvists who had an even more decisive influence on him. From the 1910s the painter thus eliminated any objective reference from painting. Colour is affirmed by its only sensitive or emotional value. By thus restoring their aesthetic autonomy to colours and lines, Kandinsky abandons the framework of the mimetic relation. The chromatic composition no longer draws its truth from a reference but from its purely affective power of unveiling an inner atmosphere (see, for example, the paintings Impression III of 1911 or Fugue of 1914).If the pictorial work makes visible or is deployed in the field of visibility, it is as a visible manifestation of what in itself always remains invisible: the Interiority or what Kandinsky also called the “Spiritual.” This is what was taken up by Michel Henry, who saw in this revolution operated by Abstraction the possibility of another phenomenality, no longer turned towards the world in the mode of perception (intentionality) but purely interior in the mode of pure affectivity or “pathos”:It is an entirely new scope that painting gives when, dismissing the Greek concept of phenomenon, it no longer proposes to represent the world and its objects, when, paradoxically, it ceases to be the painting of the visible. What then can it paint? The invisible, what Kandinsky calls “the Interior.”[6]Kandinsky’s art so represents for Henry the counterpart of what he had to establish philosophically: the phenomenality of pure affective life, that is to say self-affected, the immediate self-feeling of living subjectivity.  Wassily Kandinsky, Impression III (Concert), 1911. Oil on canvas, 77.5×100 cm. Lenbachhaus,Munich

Wassily Kandinsky, Impression III (Concert), 1911. Oil on canvas, 77.5×100 cm. Lenbachhaus,Munich

The truth of the painting is therefore no longer the blue of the sea or the sky but the blue as a pure impression of blue. Abstraction reacts against intellectual refinement by giving an absolute right to “beautiful blues, beautiful reds, beautiful yellows, materials which stir up the sensual background of man,” as Matisse wrote.[7] The green of the tree and the green as a pure sensual impression are only called “green” according to a kind of ambiguity. The first “green” belongs to the realm of intentionality and is determined in the horizon of the objectivity. The other “green” is part of emotional life which, while immanent, is in itself “un-objectivable” and therefore perfectly invisible. So, it is by relying both on the hyletic sketches of Husserl and the practical and theoretical lessons of Kandinsky that Michel Henry proposed a disconcerting thesis: the invisibility of colour and even of form. Here is how he presented it:The content of painting, of all painting, is the Interior, life in itself invisible and which cannot be ceased by being, which remains forever in its Night; the means by which it is a question of expressing this invisible content— shapes and colours—are themselves invisible, in their original and own reality anyway.[8]Michel Henry so radicalized the already radical thesis of Kandinsky relating to the Interiority of painting. While for the Impressionists or Fauvists the power of affective evocation of colours and forms was caused by their connection with the inner life, for Henry, forms and colours are the inner life, belong to it as “affective tones,” and not as references to these affective tones. The philosopher eliminated the idea of law of association between colour on the one hand and affective tone on the other.[9] It is also according to such a law that Goethe formulated his moral theory of colours. Now such an association, showed Henry very appropriately, introduces in painting “a dissociation between the content and the means of painting.”[10] By maintaining that pure lived experience is the domain of purely immanent and therefore invisible life, then by showing that colour is in itself (in its phenomenologically primary truth) an affective phenomenon, then we must admit that colour is invisible! To put it another way, we might say that the colour visible in a painting or elsewhere is only “seen” (i.e., felt) as pure inner affection. This therefore amounts to considering what is seen as one modality among others of “feeling,” i.e., as belonging entirely to the immanence of the self-affected interior life.This very radical interpretation of Interiority peculiar to Kandinsky’s theory of abstraction testifies very well to the correspondence that Michel Henry sought to establish with his own phenomenological path. This path consisted in a radicalization of the subjectivation of the sensible experience as outlined by Husserl in his project of a constitution of an autonomous Hyletics. But Henry wanted to take the phenomenological reduction further, beyond the reign of objectifying intentionality, in order to reveal that other sovereign domain of lived experience, which is that of purely immanent life, in other words of pure life, i.e., purely interior. He thus made Kandinsky’s work the pictorial precursor of his own philosophical attempt. Through his phenomenological interpretation of Abstraction, Michel Henry also offered an “abstract” (i.e. radically subjective) interpretation of phenomenology.

Wassily Kandinsky, Fugue, 1914. Oil on canvas, 129.5×129.5 cm. However, one can maybe express some reservation, not on the relevance of such a double interpretation because its force is undeniable, but on its sufficiency. Isn’t something missing? If Abstraction did bring the sensible to the foreground, to the point of making it the only ground, doesn’t this reduction to pure interiority leave aside the dimension conquered by abstract art, which is relative to this we could call with Rilke “the Open” (das Offene)[11] . Contrary to this affective movement towards the Interior, many modern works have also sought to render the ecstatic dimension of existence, in particular through an equally radical renewal of the pictorial space operated by decentering and the expression of a gap or a void.

Pierre Tal Coat According to Henri Maldiney

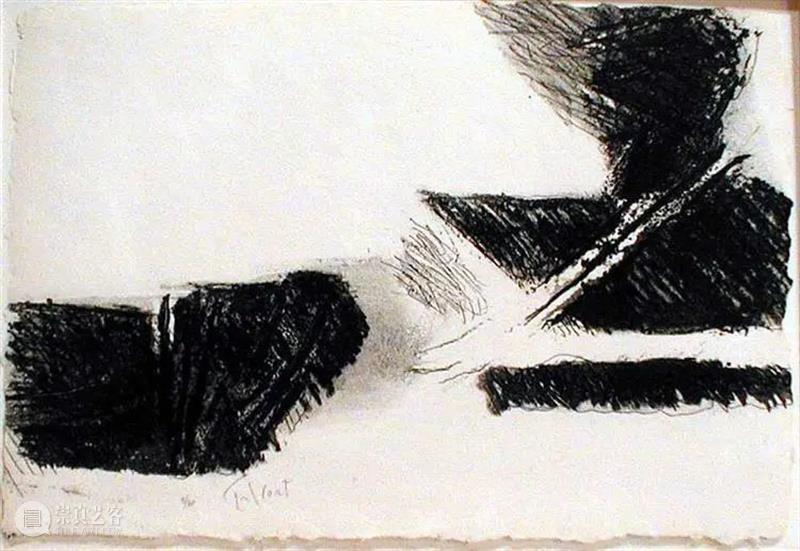

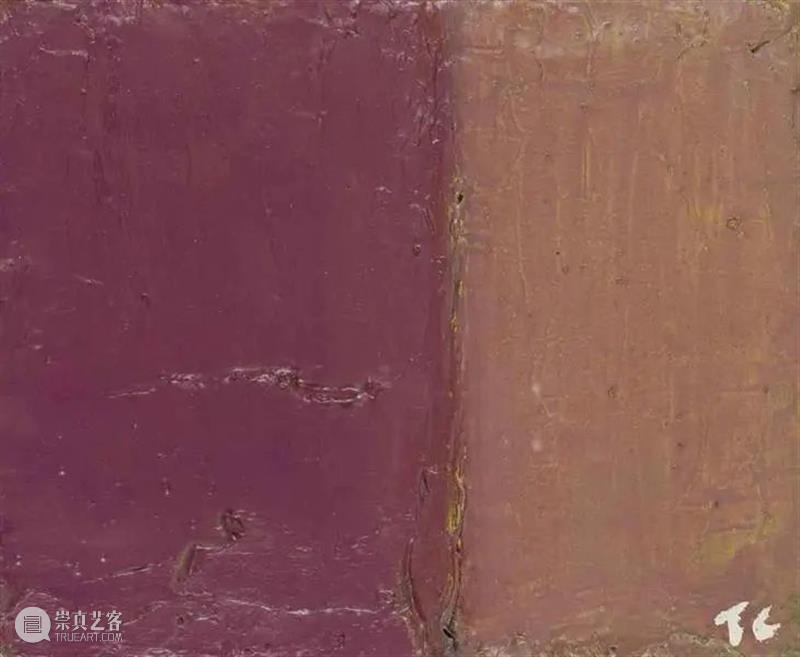

Among the great representatives of French Phenomenology, HenriMaldiney was undoubtedly the one who devoted the greatest part of his work to art in general and to abstraction in particular. His abundant work thus includes around fifteen works on art and a considerable number of articles often dedicated to contemporary works and artists such as Jean Bazaine, Pierre Tal Coat, Joan Miro, Georges Braque, Fran?ois Aubrun for painting and Francis Ponge or André du Bouchet for poetry. At the top of this non-exhaustive list of painters is the name of Pierre Tal Coat to whom he devoted at least 5 important articles and a book: Aux déserts que l’histoire accable : l’art de Pierre Tal-Coat (To the Deserts that History Overwhelms: the art of Pierre Tal-Coat). The originality of Henri Maldiney’s approach is that it combines a powerful phenomenological reflection with an intimate knowledge of the art of which he spoke about. He dealt mainly with works of his time and with artists he knew personally and with whom he even maintained deep friendship, as with André du Bouchet and Pierre Tal Coat. His thought, firmly anchored in phenomenology, where he brought together the Husserlian, Heideggerian and Merleau-Pontian paths, as well as the psychology of Binswanger, was responding to an art in the making. Among the results of this collaboration at present and at summit that he established between art and phenomenology, let us count this major articles: “Vers quelle phénoménologie de l’art?” (Towards what phenomenology of art?) and his penultimate work, Ouvrir le rien. L’art nu (Opening the Naught. The Naked Art), in which Maldiney fully unfolded this phenomenology of art in the sense of a phenomenology of abstraction. Such a perspective presupposes a broader understanding of abstraction than that currently attributed by History of art. As Maldiney wrote: “Abstraction is neither a system nor a method, it is a way of being.”[12] From such an existential horizon, Maldiney discovered abstraction even in Chinese painting. Ouvrir le rien. L’art nu thus devoted a chapter to the Shan shui (山水) of the Song period and another to the Six Kakis (or Persimmons) of Mu Qi. But as early as 1965, in an article about Tal Coat, Maldiney already compared the painter’s style to the spirit of the Chinese Shan shui:“Mountain and water. This is the style of Tal Coat.”[13] What then is abstraction? What defines a work as “abstract”? It is through the phenomenological listening to painters that Maldiney gave his answer. But since this word of “abstraction” was determined in a certain moment of the history of European art, it was mainly from the works of European and particularly French masters of abstract painting that Maldiney unfolded his reflection. Yet, abstract painting is not one and the same continuity. Maldiney distinguished so two essential moments: that of the “pioneers of Abstraction,” namely Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian and Delaunay, to which Maldiney added the tutelary figures of Cézanne and Matisse. And that of the “rebound of abstraction” represented by Nicolas de Sta?l, Jean Bazaine and especially Pierre Tal Coat. Pierre Tal Coat, [no title], 1970. Oil on wood, 27×35cm. Private collection, Zurich

Pierre Tal Coat, [no title], 1970. Oil on wood, 27×35cm. Private collection, Zurich

If Maldiney spoke of “rebound” to qualify this second moment of abstractpainting,itisbecausetherewasafallorfailureofthefirstattempt. The reasons for this relative failure lie in a “fragility of Western abstract painting” linked to the very history of Western thought which, Maldiney said, is “entirely dedicated to the full.”[14] Now this univocal tendency to “the full” is entirely achieved in the transformation of everything into an object. Objectivation — the ultimate mode of the Western-minded “full speed”— is an operation of the understanding. It is therefore from such an operation that the painter’s work of abstraction has sometimes been understood— i.e., as an operation consisting in the methodical elimination of the second qualities of objects in order to constitute generalities “abstracted” from all reality and formally organized within a network of idealities. Conversely, some abstract painters, in order to escape the reign of objectivity, have oriented abstraction in the direction of pure subjectivity. But, Maldiney said, abstraction in art “never reaches its whole determinacy as an ideal objectivity. Nor does it give itself in a subjective impression.”[15]Why? Because the relationship between objectivity and subjectivity is a logical one, which as such doesn’t concern “the strictly aesthetic dimension of our presence to the artwork.”[16] Maldiney noted this double “fall” towards false abstraction in Kandinsky and Delaunay, who both ended up by “settling in the figural or the objectity in the naked state.”[17]

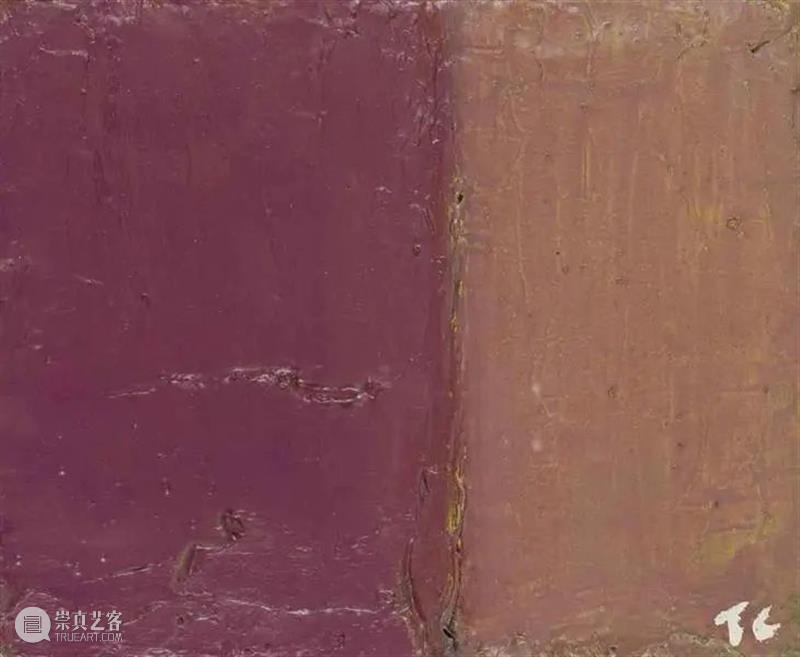

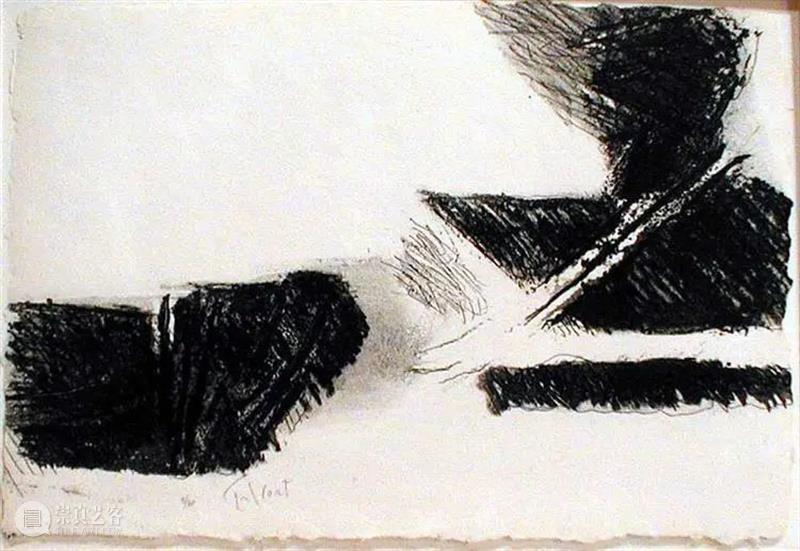

Pierre Tal-Coat,Dans le bourdonnement IITrue abstraction, that which takes on its meaning in “the properly aesthetic dimension of our presence to the artwork,” doesn’t come from a game around objective properties, their outlines and their boundaries but concerns the appearing itself and as such:To abstract is not to extract and detach from the depth of things (by which they are world) separate elements in order to consider them apart in the objective. Abstraction isn’t properly an operation, but a mode of openness that emerges in the making-a-work.[18]It is thus in the sense of the “appearing” understood not from “appearing things” but from the very movement of unfolding, emerging or opening that we must understand the truth of abstraction. To abstract is to make appear the appearing itself in a work. This is what the second generation of abstract painters devoted themselves to, among whom Tal Coat played a leading role (in France): “Letting be the being, revealing it in the movement of appearing, such is the meaning of Tal Coat’s art.”[19]Painting of appearing and therefore painting of pure phenomenality, the art of Tal Coat radically abandons the shores of objectification as well as those of subjectivation. He paints “before” this dualistic structuring of being in the world. He paints in the openness of the Being-to-the-world. In other words, it is a painting that relates to movement, to space but also to emptiness, to the primitive and to an decentered form of unity — which are among the essential characteristics of the Open as such. “Everything about Tal Coat is primitive,”[20] as Maldiney said. This primitivity, however, has nothing to do with a moment in cultural history—although Tal Coat was very interested in the rock paintings of Lascaux dating from the Paleolithic. He was primitive because he situated the painting before “the aesthetics of the window” or what Maldiney also called “the metaphysics of the vitrine,” which derives from the primacy of the objective look by which “we are irrevocably in front of…”[21] The primitivity of Tal Coat’s art therefore reestablishes a communication that objectification had abolished. From this can be born a new sense of space, which is no longer a “in front of…” or a geometric dimension, nor even a place but rhythm or breathing ensuring a unity without a point of fixation.[22]The primitive space of Tal Coat’s painting is that of the space open to us. Tal Coat spoke of the “swelling of space.”[23] It is a space that is both uni- and multi-dimensional. Furthermore, because it is a movement of openness and therefore of communication, this primitive space is also time. “Tal Coat space has the structure of time.”[24] What does this simultaneity of space and time mean? Simply that by seizing the appearing in its appearance, the painting put into a work the moment or the instant of event or happening, which essentially unites time and space. Maldiney then rediscovers, from this reflection on Tal Coat, the Heideggerian thought of “Eventness” (i.e. das Ereignis). Finally, as a painting not of the (already) happened but of the future, Tal Coat’s work is also an incessant rhythm which, as Maldiney wrote: “identifies in him the simultaneity and the depth of time and with that of space.”[25] Here again, painting rejoins phenomenology in this unity of being and appearing. Abstract painting also unified, at the same and single level the foreground and the background—so that there is only one level, that of appearing i.e., the openness of being itself.

Pierre Tal-Coat,Du c?té de la Dr?meThe Henri Maldiney’s way, which still actually represents something like the avant-garde of the French school of phenomenology, opened up and deepened mainly through his repeated and tireless encounter with painting. If its debt to Husserl and especially Heidegger was clearly acknowledged, his philosophy found through painting the path where its greatest originality was expressed. It allowed great progresses concerning the description of appearing, that is to say of phenomenality itself and no longer only of phenomena or components of constituent consciousness. Here again, as was the case with Merleau-Ponty and Henry, painting wasn’t an illustration of the philosophical thought but a decisive initiator. This is what Maldiney attested in this answer he gave in an interview to the question — “What was the moment for your philosophical awakening?”:While I was in front of the Cézanne’s Sainte-Victoire (in 1936), that of Leningrad, there was the emergence of a reality in which I was engaged. And already, confusedly, I sensed that reality only appears at the very moment of your own surprised existence. [...] To be surprised to exist is a rare thing, that is why in a life the existence is rare. And many people think outside of these moments, and therefore think completely aside.[26]Pierre Tal Coat, Terre sombre (Dark Earth), 1979. Oil on hardboard, 18×22 cm.

Pierre Tal Coat, [no title], 1960. Oil on canvas board, 27×35 cm.

As a conclusion, it is undoubtedly necessary to notice how the approach of art as considered by Merleau-Ponty, Henry and Maldiney rests on the same methodologicalbasis,whichconsistsinneverproposinganewtheory of art but discovering through the analysis of the work of art a privileged access to the very sense of phenomenality. In this, these three thinkers remained faithful to Heidegger’s approach, despite the manycriticisms they made against his work or his person. The reason for this methodical fidelity despite fundamental disagreements is undoubtedly due to the special status of art, which cannot be reduced to any other human activity. Artasacreativeandaestheticpracticeindeedassociatesthe“making-being” from the “making-appear.” In other words, art is the phenomenality itself “at work.” We can thus understand why these three great representatives of French phenomenology devoted so much time to the analysis of paintings or poems. Such a study didn’t represent an accessory of their work as a thinker but was the very heart of their phenomenological research. Doubtless the French situation of these philosophers played a large part in the excitement of their artistic interest. All of them lived in a France, which still remained one of the world centers of artistic life. Merleau-Ponty and Maldiney lived in Paris, which was still the “capital of arts.” However, the situation has changed a lot since then. It isn’t certain that the phenomenologists of the French tradition can still find in France the works and the artists who can re-open to them this privileged access to phenomenality. We therefore regret the lack of French phenomenological studies devoted to American Abstraction or to the most relevant part of contemporary art that has become international. Yet this is certainly a decisive resource for major new phenomenological breakthroughs.

[1]See Michel Henry, Phénoménologie de la vie. Tome III. De l’art et du politique (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2003).

[2]Edmund Husserl, Ideen zu einer reinen Ph?nomenologie und ph?nomenologischen Philosophie. Erstes Buch: Allgemeine Einführung in die reine Ph?nomenologie (Halle: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1913), 178.

[3]Edmund Husserl, Aufs?tze und Vortr?ge (1922–1937), Husserliana: Edmund Husserl—Gesammelte Werke, bd. XXVII (Den Haag: Nijhoff, 1989), 246.

[4]See Michel Henry, Phénoménologie matérielle (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1990).

[5]See JohannWolfgang(von)Goethe,TheoryofColours,trans.C.L.Eastlake(Boston:MITPress,1970).

[6]Michel Henry, Voir l’invisible, sur Kandinsky (Paris: Bourin-Julliard, 1988), 24.

[7]Henri Matisse, écrits et propos sur l’art (Writings and Talks on Art), ed. D. Fourcade (Paris: Hermann, 1972), 128.

[8]Henry, Voir l’invisible, sur Kandinsky, 24.

[9]Ibid., 124.

[10]Ibid., 22.

[11]Seethe8thDuinoElegy,inRainerMariaRilke,DuinoElegies:ABilinguialEdition,trans.S.Cohn(Evanston: Northwestern University Press,1989).

[12]Henri Maldiney, Ouvrir le rien. L’Art nu (La Versanne: Encre Marine, 2000), 37.

[13]Henri Maldiney, Regard, Parole, Espace (Paris: Cerf, 2012), 169.

[14]Maldiney, Ouvrir le rien, 282.

[15]Ibid., 226.

[16]Ibid.

[17]Ibid., 186.

[18]Maldiney, Ouvrir le rien, 326.

[19]Maldiney, Regard, Parole, Espace, 172.

[20]Ibid., 54.

[21]Ibid., 55.

[22]Maldiney, Regard, Parole, Espace, 58.

[23]Ibid., 172.

[24]Ibid., 169.

[25]Maldiney, Ouvrir le rien, 220.

[26]Charles Younès, Henri Maldiney: Philosophie, Art, Existence (Paris: Cerf, 2007), 182.

作者简介:Alexis LAVIS,中国人民大学哲学院副教授、杰出青年学者。国际哲学公学院(CIPh)项目主任(任期2022-2028)、法国国家科学中心(CNRS)胡塞尔文献室研究员、法国Le Cerf出版社哲学部"Asian Studies"主编、Le Monde·Religions《世界报·宗教》杂志编委、鲁昂大学哲学博士,professeur agrégé de philosophie,从事现象学和比较哲学(儒家、道家、印度佛教)研究,专精法语、英语、梵语、德语、古希腊语、拉丁语,熟练使用古汉语、意大利语。曾在法国鲁昂大学哲学院、巴黎政治学院任职。

Hermitage ~ part 14 – Kandinsky, Vasily - Composition VI

Hermitage ~ part 14 – Kandinsky, Vasily - Composition VI Wassily Kandinsky, Impression III (Concert), 1911. Oil on canvas, 77.5×100 cm. Lenbachhaus,Munich

Wassily Kandinsky, Impression III (Concert), 1911. Oil on canvas, 77.5×100 cm. Lenbachhaus,Munich

Pierre Tal Coat, [no title], 1970. Oil on wood, 27×35cm. Private collection, Zurich

Pierre Tal Coat, [no title], 1970. Oil on wood, 27×35cm. Private collection, Zurich

分享

分享