阿克塞尔·卡塞勃姆

Axel Kasseb?hmer

展期 Duration

10/13/2024-01/05/2025

地址 Venue

施布特-玛格画廊

展览现场 Installation view

展览现场 Installation view

?万一空间 W.ONESPACE

In this exhibition, Kasseb?hmer’s work is thoughtfully presented alongside scholar’s rocks, elements of Eastern aesthetics that offer viewers a new lens through which to experience his approach to landscapes. Ancient Chinese scholars cherished and connected deeply with nature, seeing vast landscapes within the small forms of stones and finding joy in the meditative practice of “wo you (卧游)” — enjoying scenery without physically traveling. This sentiment is often reflected in poetry, such as Tang poet Bai Juyi’s Record of Taihu Rock: “In essence, the Three Mountains and Five Sacred Peaks, a hundred caves and a thousand ravines, are all gathered within; a hundred spans in a fist, a thousand miles in a glance, all experienced while seated.” Ming scholar Lin Youlin wrote in Su Yuan Stone Spectrum, “A rock placed on the desk to console the longing for forests and streams,” capturing the essence of landscapes encapsulated within stones, with mountains and peaks rising on the table. The appreciation of scholar’s rocks reflects not only a scholar’s inner character but also a distilled essence of nature’s beauty. These miniature landscapes are placed on the desk, allowing for continuous contemplation.

Axel Kasseb?hmer was born in 1952 in Herne, Germany, and passed away in Munich in 2017. At the age of 14, a small sculpture he created in art class caught his teacher’s attention, who even expressed interest in purchasing it. Unfortunately, he accidentally broke the sculpture while transporting it. What could have been Kasseb?hmer’s first income-earning artwork instead unexpectedly sparked his lifelong passion and pursuit of art. His rebellious spirit manifested in his intense love for art from a young age. As a young man, he frequently skipped classes to visit art museums, even repeating a grade as a result. Despite financial hardship, he remained deeply immersed in Neoclassical works. Later, when his high school decided to cut its art program, Kasseb?hmer was outraged and stormed into the principal’s office in protest, sparking a wave of commotion. One summer, Kasseb?hmer visited the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where he encountered Gerhard Richter (b. 1932). In a hallway, he showed Richter his work. After only a few questions, Richter invited him to attend classes in the first week of the winter semester. Thus, Kasseb?hmer formally began his artistic career.

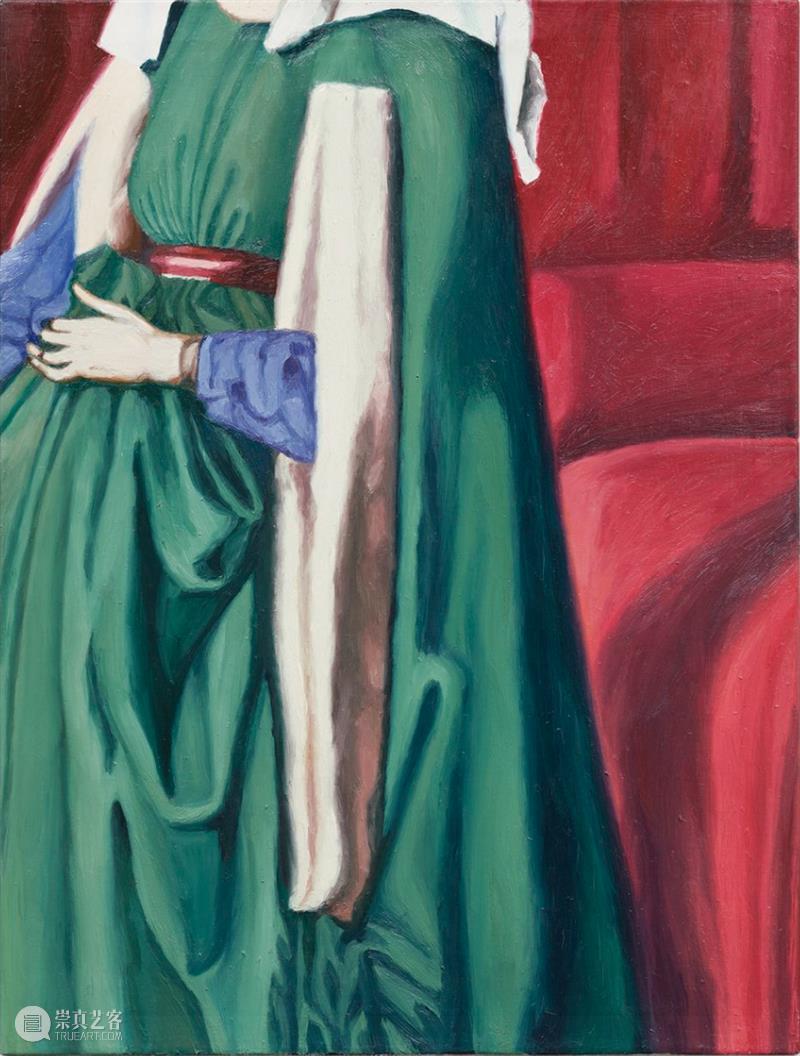

He believed art should be a pure expression of humanistic spirit, unfettered by history or extraneous elements. Thus, he began to use the language of painting itself as a medium, enlarging and reinterpreting details of iconic works to create his “Quote” series in the late 1970s, which garnered significant attention.

绿色连衣裙配红色 Green Dress with Red

阿克塞尔·卡塞勃姆 Axel Kasseb?hmer

1979

?Sprueth Magers

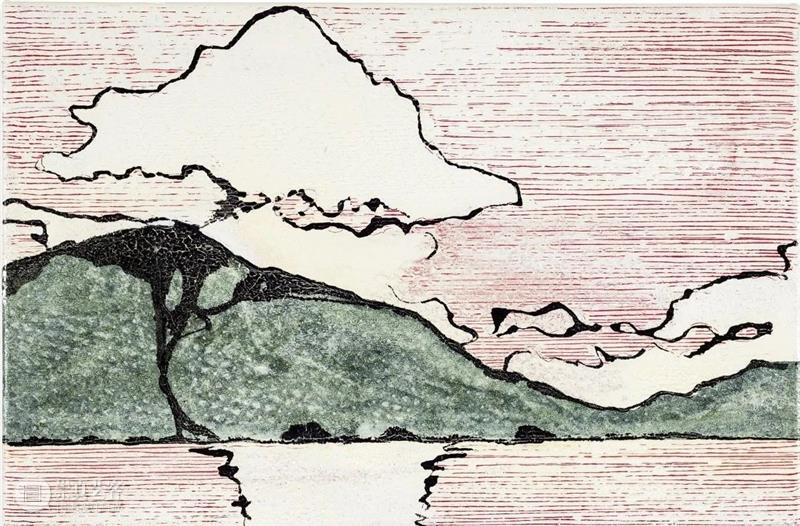

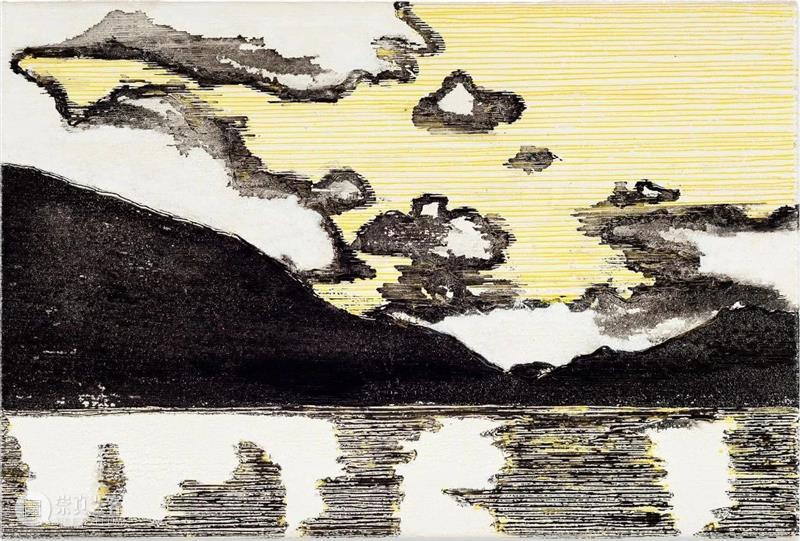

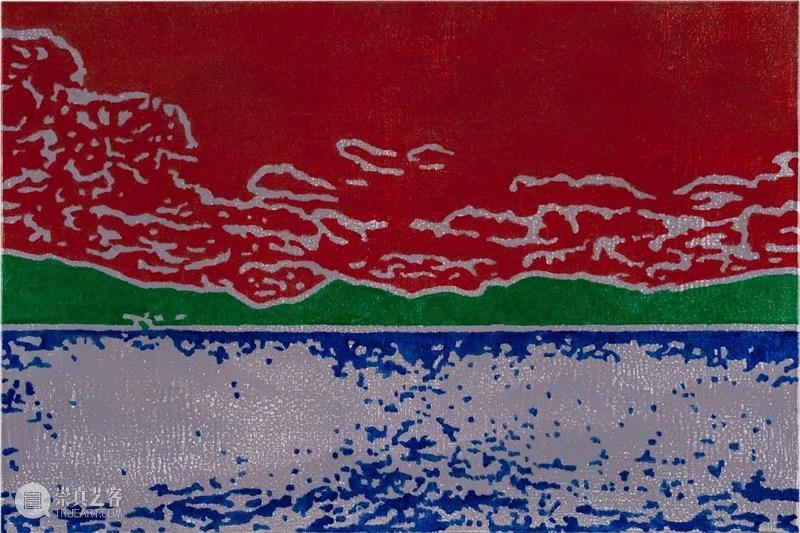

Landscape painting, as a timeless genre in art history, is continually reinterpreted by Kasseb?hmer. Reflecting on his creative path, he humorously remarked that choosing this traditional subject matter was only natural. In the early 1980s, amid growing concerns over environmental degradation, Kasseb?hmer perceptively recognized similar forms of “destruction” in certain contemporary artistic practices. This awareness led him to create a new series of tree, still life, and ocean landscapes, such as “Landscape Yellow, Green (Landschaft gelb, grün)” and “Seascapes (Meereslandschaften)”. In these landscapes, he subtly embedded reflections on environmental destruction, crafting a deeper response to the erosion within contemporary art itself. Kasseb?hmer sought to explore a form of creation that possessed its own uniqueness and intrinsic value, rather than engaging in mere satirical critique of external subjects.

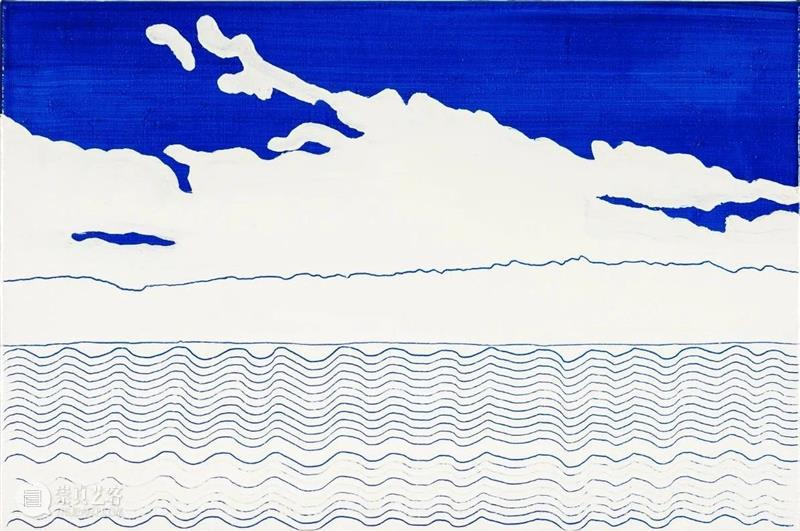

Compared to his early “Quote” series, where Kasseb?hmer invested extensive practice and meticulous attention to detail and fundamentals, his deeper exploration of landscape as a primary subject led his work to a more abstract treatment of detail, reflecting an effortless mastery honed over time. In the Seascapes series, some works employ highly fluid, transparent oil paints, making the flow of the pigment unpredictable. “It (the work),” he noted, “had to result in something that was believable to me, but very much driven by the self-movement of this fluid paint.” Kasseb?hmer avoided overloading his paintings with conceptual narratives, focusing instead on the purity of painting practice —— on material, art-historical themes, and the conveyance of his own visual language. His works stood resilient against an era eager to transform everything into media images, fundamentally undermining the essence of painting. Instead, he strove to showcase a unique language that only painting could articulate. Art critic John Quin aptly remarked in his FRIEZE magazine article, Axel Kasseb?hmer’s Rebellious Landscapes (Vol. 195, 2018),“He would be badder than the bad boys by painting good paintings. ”

——Art critic John Quin

In art, there are rarely single solutions to any problem; a similar principle of diversity can also be found in music. Kasseb?hmer explained, “Just as motifs are introduced and then varied harmoniously in music, I do the same. And what you can see very clearly is that depending on how you vary, the emotional character changes too; you only need to change a few notes, and suddenly an optimistic, positive major motif becomes a minor motif and sad. You can and must do similar things in painting. I wouldn’t want to paint, for example, only blue landscapes all the time.”

?Timo Ohler

In Nr. 82, the clean, silhouetted lines evoke Henri Matisse’s Themes and Variations (1943) and his famous late Paper Cutout series, with their graceful, shadowless lines.

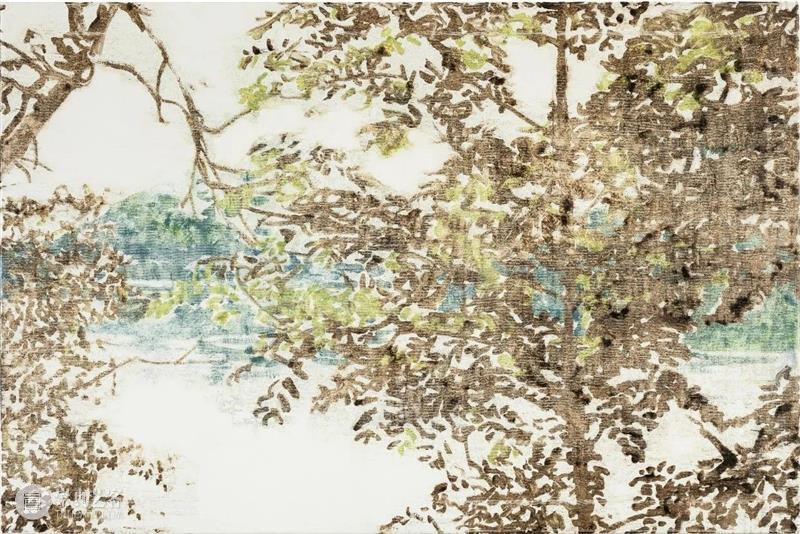

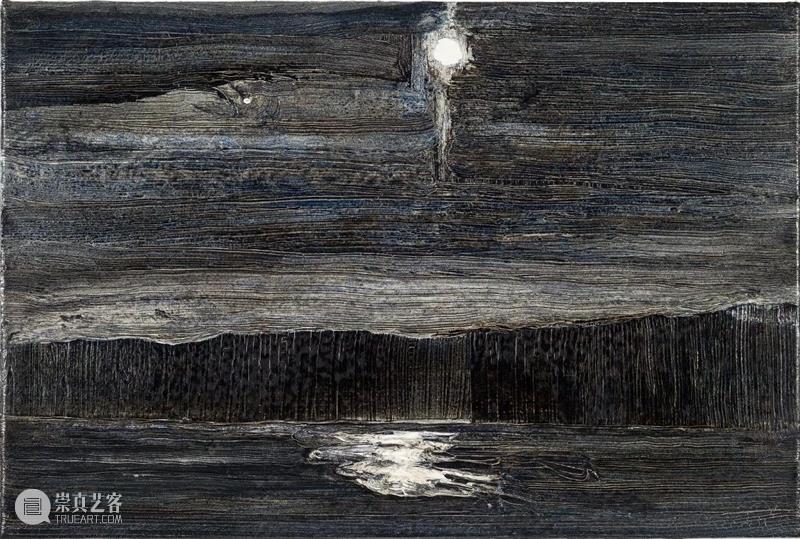

瓦尔兴湖 No.15 Walchensee, Nr. 15

2010

?Timo Ohler

In Nr. 15 and Nr. 100, Kasseb?hmer draws from Edvard Munch’s lithographs The Scream and The Sun. Notably, in the nocturnal Walchensee scene of Nr. 15, his depiction of the moon is striking: he outlines the moon’s glow with fine vertical lines and uses fluid strokes to capture the shimmering lake reflections, skillfully conveying the tranquility and soft illumination of moonlight across the water.

2010

?Timo Ohler

2011

?Timo Ohler

2012

In Nr. 54 and Nr. 100, Kasseb?hmer also adopts the thick lines and comic-inspired print style of Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997).

Kasseb?hmer believed that while some viewers may feel disappointed by the lack of expected elements in landscape paintings, the meditative nature of landscapes should not be cluttered with excessive detail. This may explain why figures rarely, if ever, appear in his seascapes and landscapes. Though he could never fully articulate why he avoided depicting people (except in self-portraits), he once remarked, “It doesn’t necessarily follow that you say the most about people when you depict them. I do want to say something about people, but I don’t want to depict them.”

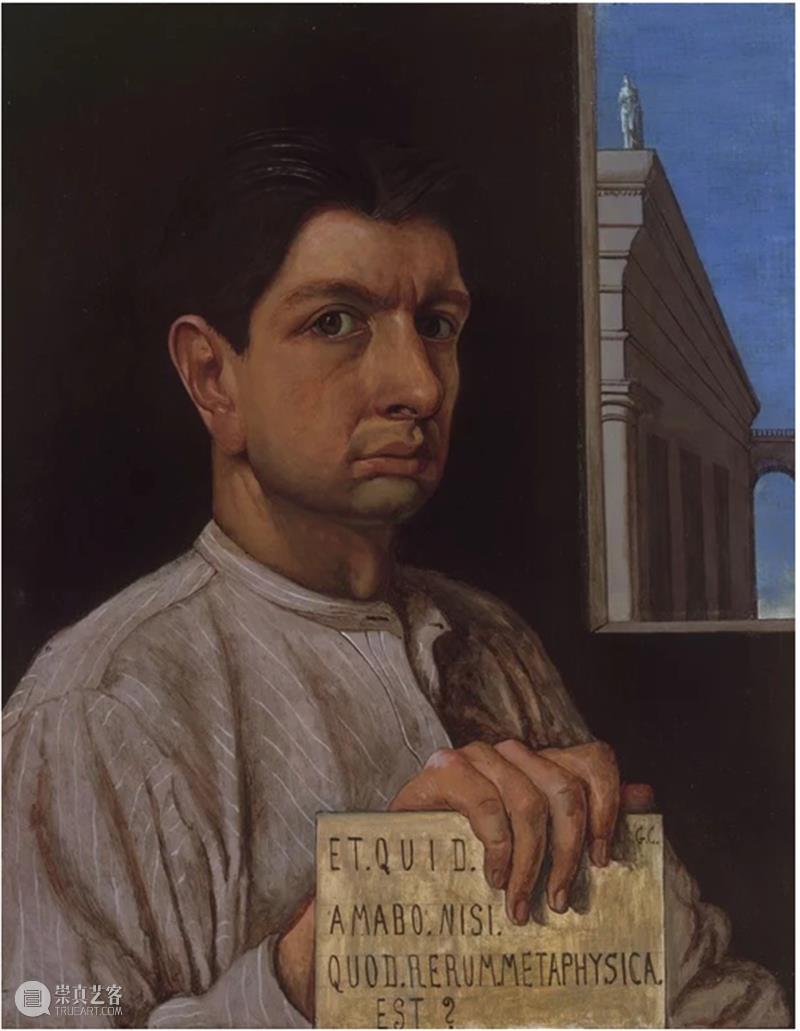

(2). 自画像 Self-portrait | 乔治·德·基里科 Giorgio de Chirico | 木板油画 Oil on wood | 50.2 x 39.5 cm | 1920

Kasseb?hmer’s thoughts on simplification and empty space can be seen in his description of Giorgio de Chirico. In a small self-portrait with an inscription (Selfportrait, 1920), de Chirico used a subtle painting technique:“He’s wearing a shirt with pinstripes—and the stripes aren’t painted on the top edges of the folds, but you can still see them running through. Observing things like that, realizing that you sometimes have to leave things out to make them look even more accurate—that’s something you have to figure out first—and he saw that as a young man.”The inscription in the self-portrait is crooked, echoing the Japanese appreciation for the essence and imperfection of things. In Japanese culture, a piece of pottery is not expected to be perfect, as perfection belongs to machines, not to humans. It speaks more to revealing the truth and authenticity of life.

展览现场 Installation view

展览现场 Installation view

?万一空间 W.ONESPACE

In the latest period of his life, Kasseb?hmer gazed upon Lake Walchensee and recorded the scenes he perceived in his heart through painting, traversing art history from past to present. His works are both a rebellion against the present and a tribute to and continuation of classical masterpieces that span centuries. More than ten years later, his paintings are now engaging with us in a different country and cultural context, engaging us in a dialogue regarding the human experience of nature. The Walchensee still exists —— the landscape he saw, the landscape in his heart —— and now we, too, have the chance to witness it.

Article/ Xing Yunshu

阿克塞尔·卡塞勃姆(Axel Kasseb?hmer,1952-2017)在1970年代就读于杜塞尔多夫艺术学院,师从格哈德·里希特(Gerhard Richter,1932- )。自2001年起,他在慕尼黑美术学院任教。卡塞勃姆的作品曾在多家著名机构展出与收藏,包括德国的Leopold-Hoesch博物馆(2014)、波士顿美术馆(1994)、瑞士圣加仑美术馆(1994)、纽约古根海姆博物馆(1989)、慕尼黑艺术协会(1986)、纽约现代艺术博物馆等。

卡塞勃姆开创了一种激进的、概念性的绘画方式,刻意挑战当时主流的绘画趋势,这也使他成为了欧洲绘画界的重要人物。他的作品以对绘画中失落价值的敏锐感知而为人所知,在一个绘画媒介的未来不断受到质疑的时代中,他的作品自信地展现了这些传统媒介的先锋性价值。

Axel Kasseb?hmer (1952-2017) was a German painter studied under Gerhard Richter at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in the 1970s. Since 2001, he is teaching at the Kunstakademie München. His works have been shown in institutions including Leopold-Hoesch-Museum, Dueren (2014), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1994), Kunsthalle, St. Gallen, Switzerland (1994), The Guggenheim Museum, New York (1989), Kunstverein München, Munich (1986), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, among others.

展览相关阅读 Related Readings

已展示全部

更多功能等你开启...

分享

分享